All rights reserved.

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce, or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018.

The passages: "Now that the owner... temper tantrums and all" and For the rest of her life... to her service" are from Mrs. Jack, by Louise Hall Tharp, copyright 1965 by Louise Hall Tharp. Reprinted by permission of Marshall A. Tharp and Carey Edwin Tharp.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

On the morning of August 27, 2003, two men in their forties drove up to an enormous mansion called Drumlanrig Castle, in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, and paid six pounds apiece to take the tour. The house was one of the residences of the duke of Buccleuch. A great art collection hung at Drumlanrig, including paintings by Rembrandt and Holbein. But a single picture outweighed all the others in importance and valuea tiny, radiant painting by Leonardo da Vinci, the Madonna with the Yarnwinder. Only a few paintings in the world can be attributed with confidence to the hand of Leonardo; one of them is the Mona Lisa, in the Louvre in Paris, and the little Scottish picture is another. People were drawn from all over the world by the duke's Madonna, and so were the two men who followed the guide that Wednesday morning as she led them to the staircase hall where the Leonardo hung. Just after eleven o'clock they snatched the forty-five-million-dollar painting from the wall, rushed from the house, and got away.

Such crimes appear daring, as if the perpetrators were characters who might have been played by David Nivenurbane, catlike malefactors who rob the rich with breathtaking deftness. In fact the crimes take no special skill; art thieves steal art because it is easy. Compared to a like amount of cash, art is pitifully vulnerable. The duke would not have hung forty-five million dollars in banknotes beside the stairs in an isolated castle for anyone with six pounds to come in and see. But it is not in the nature of art to be put away in steel vaults in well-guarded banks. Treasures hang across Europe in remote houses and churches, abbeys and libraries, and in the United States in dozens of small museums. Every year thieves steal ten billion dollars' worth of them.

When the alarm went up at Drumlanrig, police poured into the countryside. Roadblocks sprang up throughout Dumfriesshire, and helicopters scoured the terrain around the estate. When no trace of the picture could be found, art-theft experts trotted out the usual wisdom for the press: that the painting could never be sold on the open market; that the popular idea of some rich, besotted collector prepared to buy a stolen masterpiece was ridiculous; and therefore that the thieves' only reasonable hope for a reward was ransom.

In fact this list of options missed the most common fate of high-end stolen art: a vast, criminal marketplace in which pictures are readily collateralized. When a great painting is stolen, its value is immediately blazoned in the press, often as part of a headline. Any potential criminal buyer is therefore assured of two important details of an item that might come into play: authenticity and worth. He would know that in the case of a picture valued in the tens of millions of dollars, the insurers would be eager to retrieve it, whether they were still on the hook for a payout or had already compensated the owner. In many jurisdictions it is illegal to benefit thieves by paying them ransom. Ransom is paid anyway, often called a "reward for information." Criminals can happily wait for years for such a disposition, because the object has cost them nothing to acquire. Moreoverand this is crucialthe art may already have begun to pay its way. Stolen paintings are now accepted as collateral by some criminals with drugs to sell. In this way the booty functions as a currency, accepted as surety for something else of valuedrugs.

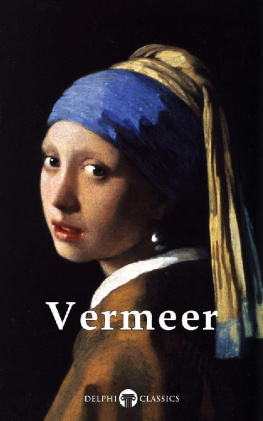

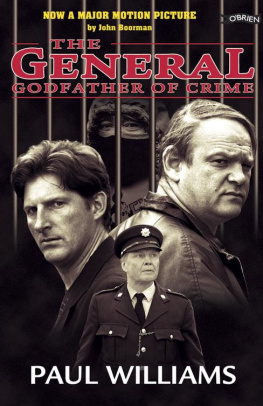

The discovery that stolen art was working as a kind of cash in the criminal world was made by a team of policemen who came together for a few years to break a string of famous cases, and who brought to a close one of the strangest, longest-running sagas in the annals of art crime: the case of a Vermeer, stolen twice from the same house. The trail led not only to the destruction of a legendary criminalMartin Cahill, "the General"and the exposure of a dark, new trade in purloined art, but to a pair of amazing discoveries: one about the painting itself; the other about the way Vermeer worked.

Art is embedded in a world animated by both money and intellect. History and scholarship single out certain artists for veneration, and the art market expresses this judgment in terms of money. In recent times the money valuations have shot up spectacularly, and thieves have taken notice. The story that follows, which began in a great mansion in the Irish countryside, reveals what high prices have createdan underworld bazaar with a ravenous appetite for art.

The Irish Game

In Ireland lies a gray stone palace, in a valley by the Wick-low Mountains. The mountains themselves are dry and desolate, and an unfriendly wind picks its way across the heath. Little roads wind here and there in the hills, and criminals drive out from Dublin to make the place their haunt. It is a wonder that the house lay unmolested for so long in its park below the hills, tethered against the drenched green sward of Ireland.

The palace of Russborough House comes into view quite suddenly. At a bend in the N81 from Blessington, a high wall crumbles away, and there, a quarter mile up the pasture, spreads Russborough's long facade. From end to end it runs for seven hundred feet. Sometimes the sun strikes the house, and the stone glows with a silvery light, and a kind of trumpet music seems to float in the air, proclaiming a world impossibly rapturous and remote.

The Leesons built Russborough. Their ancestor came from England as a sergeant in the army of the prince of Orange, who laid waste the Catholic armies of James Stuart in 1690 at a battle on the River Boyne. This defeat completed the destruction of Catholic power in Ireland. After the Battle of the Boyne a long period of minority rule ensued, known as the Protestant Ascendancy. The Leesons were part of this empowered group. They became brewers and Dublin property speculators, and prospered rapidly. They married well, applied for a patent of nobility, and after that passed promptly upward from the baronetage into the peerage, becoming earls of Milltown. All they needed was a decent house, and in 1741 they commissioned the foremost architect in Ireland, Richard Castle, to build it.