Contents

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee: A Disturbance in the Courtyard

Chez Tortoni: The Art Detective

A Lady and Gentleman in Black: It Was a Passion

The Concert: The Picture Habit

Cortege aux Environs de Florence: The Art of the Theft

Landscape with an Obelisk: Something That Big

Ku: Unfinished Business

Three Mounted Jockeys: Infiltrate and Infatuate

Self-Portrait: I Was the One

Program for an Artistic Soiree: Any News on Your Sid

Program for an Artistic Soiree II: Wheres Whitey?

La Sortie de Pesage: Put My Picture on the Cover

Finial: Like a Spiderweb

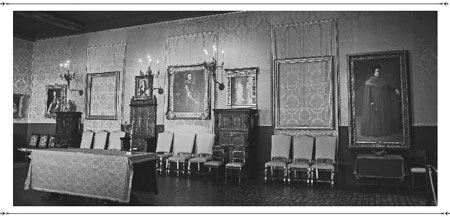

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

THE STORM ON THE SEA OF GALILEE

A Disturbance in the Courtyard

Boston, Massachusetts

Around 12:30 a.m.

March 18, 1990

O N THE EAST SIDE of Palace Road, just beyond the harsh glare of a sodium streetlight, two men sit in a small, gray hatchback. The man in the drivers seat is stocky and broad shouldered, with round cheeks and squinty, James Dean eyes. The other man is shorter, standing just under five foot ten. He has the worn, craggy face of a hard-working longshoreman. A pair of square, gold-framed glasses perch on his nose. Both men are dressed as police officers, and they look the part, dark blue uniforms, eight-point service caps, and the nylon, knee-length coats that beat cops use to stay dry on wet New England nights.

A light rain fell earlier in the day. Water beads on the window of the hatchback. Across the street, a few late-night revelers spill out of an apartment building. Theyre youngseniors in high schooland just left a college-dorm party because the beer ran out. Now they linger on the street, talking and laughing, their voices thick and boozy. Its late on one of the biggest nights of the year, St. Patricks Day. They have to go somewhere, one of the revelers says. Should they try and sneak into a bar on Huntington Avenue? Or pick up a case of beer and head to someones house? Jerry Stratberg jokes with one of his friends, pulling her onto his back and wobbling her piggyback style south along Palace Road. He seesaws down the sidewalk for a few yards. She taps him on the shoulder. Watch out, theres a cop in that car over there, she says.

Stratberg sees the broad-shouldered man in the drivers seat of the hatchback and steps toward him. Through the thin fog, they stare at each other, the broad-shouldered man giving Stratberg a flinty look that says back off, go home. Stratberg notices the mans unusual eyesthey look almost Asianand then spots the Boston police patch on his shoulder.

What are the cops doing here? Looking for thieves? Drug dealers? There have been a spate of muggings in the area, and in October, a gunman shot and killed a pregnant woman waiting at a stoplight a few blocks away. Still, Stratberg thinks, nothing good can come from this. Hes under the legal drinking age, a few months away from his high school diploma. Lets go back and tell the others, he says. His friend slips from his shoulders. The two soberly cross the street. They whisper quietly with the group, before they all hop in a car and roar off.

The street falls silent. Some oak trees quiver in the wind. Then, shortly after 1 a.m., the two men step onto the sidewalk, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum looming above them like a castle. The nineteenth-century heiress Isabella Stewart Gardner designed the four-story building as a replica of a Renaissance-era Venetian palazzo, with soaring balconies, stone stylobates, and a blooming courtyard brimming with lofty palms and hothouse jasmines. Art was Gardners passion, and she built a world-class collection, packing her museum with tens of thousands of treasures, including works by Titian, Velazquez, Raphael, Manet, and Botticelli. The museum also contains the only Cellini bronze in the country, the first Matisse acquired by an American museum, and Michelangelos tragically moving Pieta .

Flamboyant, imperious, with a deep belief in the redemptive power of art, Gardner built intimate galleries for her masterworks, each room extolling a different theme, each one its own creative stew. Theres a quiet, calming Chinese Loggia; a Gothic Room that recalls a medieval chapel; a Yellow Room lined with pastel-toned paintings by J. M. W. Turner and Edgar Degas. In her will, Gardner forbade any changes to her museum. She wanted her work of art to always remain her work of art. Nothing could be added or taken away. Not a Chippendale chair, not a Rembrandt canvas, not a bamboo window shade. Everything must remain in the same Victorian patchwork of wood-paneled corners and draped alcoves, or the trustees would be required to sell off the collection and donate the profits to Harvard University. And from Gardners death in 1924 until that March 1990 evening, it was a wish faithfully kept.

The two men move to the side entrance. Next to the large wooden door is a white buzzer. One of the men presses it.

Through an intercom, a security guard answers.

Police. Let us in, the man says. We heard about a disturbance in the courtyard.

Inside the museum, sitting in front of a console of four large video screens, Ray Abell thinks for a moment. Hes short and gangly, with a long mop of curly hair that cascades over his shoulders. A student at the Berklee College of Music, he wears one of his favorite hats, a large, wide-brimmed Stetson. For him the job is little more than a rest between rock shows, and he will often gig with his band at a local bar before he strolls into the museum just before midnight. The third shift can be hauntingly spooky. Late at night, the floorboards squeak and moan, bats dash around the Italianate courtyard, their wings softly fluttering in the night air. But the job doesnt require much work, and Abell will usually wile away the hours in the way that most guards wile away the hours, reading magazines, playing cribbage, waiting for the moment when the sun comes up and filters though the courtyard in a rosy haze of light.

Abell stares at the video screen images of the two men. Tonights shift has already been too busy for his liking. Thirty minutes earlier, while he was doing his rounds, a fire alarm went off in the conservation lab on the fourth floor. He ran up the wooden stairs and into the room, the bright lights of the alarm strobing the walls. But there was nothing. Then, some ten minutes later, the alarm rang in the carriage house. He sprinted outside, and with the beam of his flashlight he speared the darkness, looking for flames for smoke, any signs of fire. Again, nothing. And on the video screens in front of Abell, the men look like cops. They have police patches on their shoulders. Insignia dot their lapels. Maybe someone managed to get into the courtyard? Or there was someone in the carriage house? Despite orders never to let anyone into the museum, Abell buzzes the men inside.