For Alessandra and Gabriela

Two remarkable women in their own right

The socialist of another country is a fellow patriot, as the capitalist of my own country is a natural enemy.

J AMES C ONNOLLY , Irish Republican, in a quote posted on the wall of Rose Dugdales office

To gain that which is worth having, it may be necessary to lose everything else.

B ERNADETTE D EVLIN , Irish civil rights leader, in The Price of My Soul

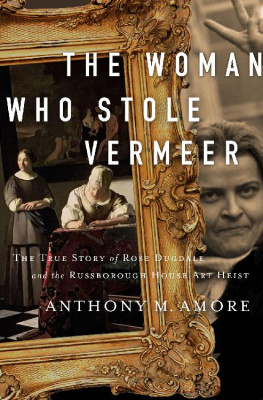

INTRODUCTION The Revolutionary Rose Dugdale

W hen Rose Dugdale became international news in the mid-1970s, she emerged as an emblem of the times. Fiery, bold, and brash, she defied the conventions of her birth and of her gender in everything from action to attire. At the same time, she was generous, articulate, and unquestionably bright. Her criminality, combined with her lineage, her degree from Oxford, and her doctorate in economics, made her a curiosity to journalists not only in Ireland and Britain but in North America as well. She was media gold, having abandoned a life of wealth and leisure to take up arms in operations that would almost certainly, if not intentionally, lead her to prison.

Dugdale was also a radical, not just politically but criminally. No woman before her or since has ever committed anything resembling the art thefts for which she served as mastermind, leader, and perpetrator. For these and other crimes, she carries no regrets or remorse and offers no alibis. The ethical decisions she made during her life were her own, formed after years of intense study in universities and on the ground, from Cuba to Belfast.

Hers was an age of conflict. The antiwar movement, assassinations and riots in the United States, massive student protests in major cities in Europe, civil wars from Guatemala to Ethiopia, a recent revolution in Cuba, a coup in Portugal, and the Troubles in Northern Irelandthese were the fires burning around the world, and she studied all of them.

Hers was also an era of liberation, in its many manifestations. Liberation theology was emerging in Latin America, a symbiosis of Marxist socioeconomics and Christian thought meant to combat greed and, thus, liberate the impoverished from their oppressors. Similarly, the Black Power movement was on the rise, and Kwame Ture (the former Stokely Carmichael) and Charles V. Hamilton had recently published Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, examining systemic racism in the United States and proposing a liberation from the preexisting order in the country. The Black Power movement would capture Dugdales attention throughout her life. There was sexual liberation, with free love and changes in age-old gender roles. Dugdale would test these waters, especially in her open relationship with a married man to whom she provided financial support and engaged in a sort of domestic mnage trois. There was the womens liberation movement, which had started at around the time of Roses own ideological awakening in the late 1960s, and from the rejection of societal expectations as a young aristocrat to challenging dress codes at Oxford to taking the lead in militant operations in a way few women of her day dared, Rose reflected that movement in the most radical ways. And, of course, there was the struggle for the liberation of Northern Ireland from British colonial rulethe struggle that would become more important to Rose Dugdale than any other cause, or person, in her life.

Dugdale was unusually earnest in her revolutionary activism. She had no thirst for power, no visions of grandeur for herself; her visions were only for the audacious goals of a free Ireland and the end of capitalism. She found fulfillment in joining the fight and in participating in a grand fashion. While much of what she did and what she tried to accomplish was ill-advised and unquestionably criminal, her motives were no secret and her justifications clear. They were also formed wholly on her own and were not the result of her having fallen under the spell of some charismatic man, despite such claims from lazy onlookers.

Her unbridled zeal for her causes was the topic of countless contemporaneous journalistic opinions, and they typically lay somewhere on a continuum, with Reluctant Debutante Rebelling against Her Parents at one end and Poor Little Rich Girl Radicalized by Her Boyfriend at the other. In fact, neither of these is completely accurate. Yes, there are elements of rebellion against her parents wealth, and it is indeed correct that her militancy intensified while she was with boyfriend Walter Heaton, but the truth is that her convictions were the result of her own studies, her own mind, and her own soul. Rose Dugdale was her own personnot her parents, not Heatons, and not the IRAs.

A major flaw in prior examinations of Dugdale is that, generally speaking, they have focused on the superficialon frivolous matters such as her looks, her hair color, her choice in attire, her onetime wealth, the age difference between her and her love interests, her pedigree, and her rsum. A closer examination of the woman reveals that none of these were the things about which she chose to speak. Ask her about her youth hunting on the family estate, and shed tell you about the utility of learning to use a rifle. Ask her about her being presented before the Queen, and shed tell you about the money wasted that could have gone elsewhere. Ask her about her role in university sit-ins, and shed smile and talk of student uprisings around the world at the time. And while you were certainly entitled to disagree, she had no time for argument. In short order, Rose Dugdale had decided that she had studied enough about economics at university, learned enough in Cuba, read enough about the behavior of the British Army on Bloody Sunday, and seen enough during her trips to Derry and Belfast to have any interest in winning you over with reason or debate. She was fighting a war, and she had made the deliberate decision that she was willing to take many risks, and, if necessary, many lives, to bring change to the world she saw around her.

Dugdale was not the only woman to fight on the side of the Irish Republican movement. An entire division, the Cumann na mBan (the Irishwomens Council), consisted of women eager to lend paramilitary efforts in support of the men. While most of their work was behind the scenes, there were women fighting on the front lines. In addition to the famous exploits of IRA members Dolours and Marian Price, whose bombings of famous London landmarks and subsequent hunger strikes will be described in detail in these pages, women participated in a number of operations involving extreme violence. In the very same month the Price sisters bombed London, two girls lured three young British soldiers into a house by inviting them to a party. Once inside, the soldiers were killed. Four days later, two other teenage girls were arrested with a 150-pound bomb in a baby carriage. Before the end of 1973 alone, additional women were arrested for attempted bombings, shootings, possession of weapons, and even a rocket attack on a British Army post.

Even beyond these female militants, Rose Dugdale was a groundbreaker in terms of her genres of criminality. Her involvement in an aerial assault on a police station marked the first attack of its kind. Not since World War II had bombs fallen from the sky in the United Kingdom. Yet as daring as that was, it is not the venture from which her notoriety sprang. Instead, it was her theft of nineteen paintings from the Beit Collection in 1974 that left the greatest impression. That it was thought to be the largest such heist in history was remarkable; that the mastermind was a woman was unprecedented.