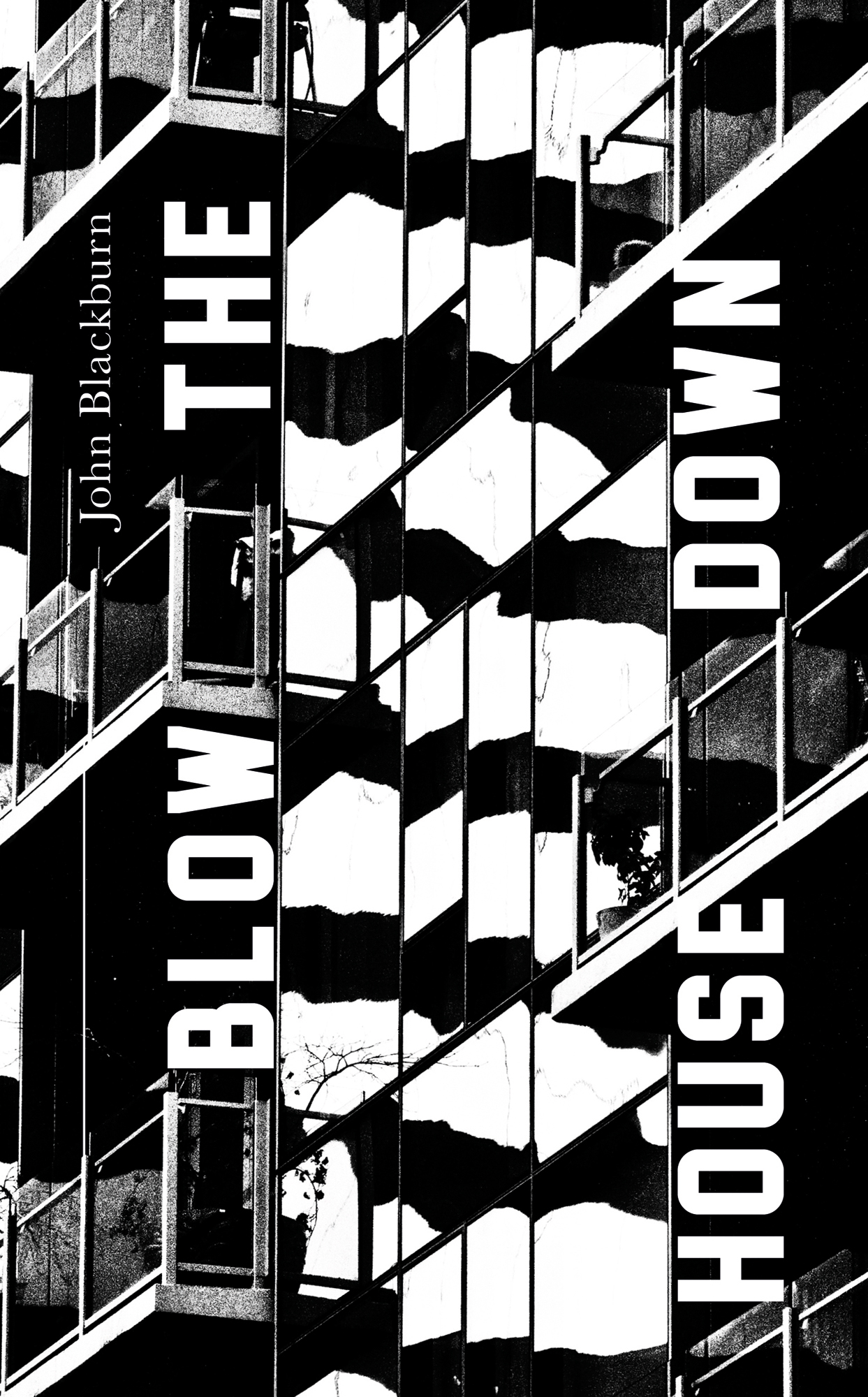

BLOW THE HOUSE DOWN

JOHN BLACKBURN

with a new introduction by

ADRIAN SCHOBER

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Blow the House Down by John Blackburn

First published London: Jonathan Cape, 1970

First Valancourt Books edition 2017

Copyright 1970 by John Blackburn

Introduction 2018 by Adrian Schober

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher, constitutes an infringement of the copyright law.

Cover design by Kerry Squires

A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER

Republishing or reading old novels can be a tricky thing. In many cases, the themes, ideas, and language contained in them do not reflect our current norms or values. Sometimes they can even be offensive. This novel was written half a century ago and deals with a subject that was then, as it is now, highly sensitive, namely that of race relations. We think any fair reading of the book will make it evident that to the extent John Blackburn had any purpose in writing it other than to spin an exciting yarn, it was to promote tolerance and condemn racism. However, in attempting to reflect authentically the real-life situation in England at the time, Blackburns novel includes a few passages in which both white and black characters use epithets that would likely not be considered acceptable in a new book published today, including one particularly offensive term used by many other writers whose books we still read, including Twain, Faulkner, Hemingway, and Harper Lee, among others.

Valancourt Books aim is and always has been to make available out-of-print works that we consider to have literary, historical, scholarly, or other value. In his lifetime, Blackburn was considered by some critics to be the foremost British writer of mystery and horror fiction, and we think it essential that all his books, including this one, be taken into account when reevaluating his significance in the twenty-first century. For this reason, and because of the historical interest discussed in Dr Schobers introduction and because it remains a rollicking, exciting page-turner even today we have reprinted it here without censorship or alteration. Readers who might be offended by sensitive content may wish to choose one of Blackburns other fine thrillers, fifteen of which we have previously published, instead.

INTRODUCTION

In introducing this reprint of John Blackburns Blow the House Down to the twenty-first century reader, one feels obliged to issue a trigger warning. First published in 1970 , the novels lurid treatment of the subject of interbreeding or miscegenation, not to mention its broad stereotyping of class and race, may be troublesome, verging on offensive. As a work of suspense, the novel requires us to appreciate both its socio-political background and how this contributes to the plot. For instead of the Cold War fear and paranoia of his other stories, Blackburn here seeks to exploit anxieties about race, immigration and civil unrest during one of the most turbulent decades in British history: the 1960 s. Subjecting the racial politics of one of your favourite authors to this kind of retroactive scrutiny can be hard going! Despite the authors best intentions, such scrutiny may reveal a passive, unexamined racism, and so it is with Blackburn. All things considered, I find the novel to be generally tolerant and enlightened.

The plot of Blow the House Down is pretty wild. The aged, infirm Sir George Strand is a world-renowned architect responsible for the design of a block of high-rise flats, which will help alleviate the housing shortage in the working-class town of Randelwyck. As the brainchild of Michael Mallory, one of the towns most prominent citizens, Mallory Heights supports four bridges designed to bring together white and non-white/immigrant tenants, and thus promote harmony and integration. But at a mayoral banquet a Berlin professor of engineering alludes to misgivings about the structure to Paul Gordon, a quantity surveyor for a civil engineering firm. The professor is killed in a mysterious street accident before he can make his statement. Town hall secretary, Janet Fane, is convinced that she has seen the bridges of a model of the structure move in a wind tunnel simulation, which fills her with dread. Meanwhile, rumours and bad press cast doubt on the safety of Mallory Heights, which worries slum dwellers Jack and Hilda Baxter, who have been allotted a flat in the Heights. Later, a fanatical physicist, Dr Baylis, threatens to blow up the building with an experimental substance called Terradyte K. Unsure about whether Baylis was acting on his own, police uncover a link between him and an underground organisation called Gods True Sailormen, which is hell-bent on stamping out miscegenation. But what is the connection between this organisation and Sir George? And what does this have to do with the structural integrity of the Heights? Or, for that matter, the local legend of the Skulda, a great wind-blowing dragon?

The fictional town of Randelwyck in north-east England is almost certainly an allusion to the town of Smethwick (four miles outside of Birmingham) in western central England, which in the early 1960 s was riven with socio-political tensions and conflicts vis--vis race and immigration. In the general election of October 1964 , support for British Conservative candidate Peter Griffiths was bolstered by his partys unofficial If you want a nigger neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour slogan, as part of a campaign that is widely seen to have exploited the racist underbelly within the British working class during the post-war period. This period witnessed a huge influx of immigrants from British Commonwealth countries such as Jamaica, India and Pakistan. But the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act and subsequent acts sought to stem the flow of immigrants from these countries. And so when Griffiths snatched the seat of Smethwick from pro-immigration Labour MP Patrick Gordon Walker, this seemed to usher in an era of racist politics, which would culminate a few years later in Enoch Powells infamous Rivers of Blood speech, delivered in Birmingham on April . We must be mad, literally mad, he declared, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some , dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population... As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood.

As a powder keg for racial tensions, Randelwyck is almost a mirror image of Smethwick. In the novel, as in real life, the presence of Britains new arrivals, housing shortages and overcrowding are inextricably linked. Indeed, Blackburn repeatedly makes this point throughout the novel: During the last six years, Randelwycks coloured population had swollen to the highest percentage in the country, the housing shortage had become acute, and schools and hospitals so cramped as to be almost unmanageable. Tension was at breaking point... (p. ). Adding to the tension is the hate-filled rhetoric of a racist preacher, the Reverend Judson, and the competing interests of nationalists, British Maoists, the Youth Power Group, and race-based factions. In pursuing the connection with Smethwick, we may note how

Housing received relentless attention in the [local weekly] Smethwick Telephone and was consistently intertwined with other concerns about the alleged local impact of West Indians and South Asians, particularly concerning sex and immorality, public health, violence and crime. Stories of white women approached by, assaulted or molested by, or cohabiting with Jamaicans, Indians and Pakistanis invariably identified by their colour or place of origin continually made the headlines... Sex and sickness often came together. Immigrants, it was proclaimed, had inordinately high rates of venereal disease, tuberculosis and leprosy that they spread among the local population and thereby burdened the National Health Service and the welfare state. Not only health but the national culture as a whole (and, by implication, the racial qualities associated with Englishness) was jeopardised by sickness and miscegenation.