P.O. Box 7355

Parallax Press is the publishing division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

I am from there. I am from here.

I am not there and I am not here.

and I have two languages.

I forget which of them I dream in.

Foreword

When I was nineteen, I took my first art class with the teacher who taught me how to draw. For our final assignment, a self-portrait, I drew a larger than life version of me, posing behind a headless statue. I have lost track of the original drawing, so I drew a smaller version for you here.

The reason for centering my hands was to say, I am what I do, not what I appear to be. That part I still believe. The rest was put together to the best of my ability with what was available to me at the time. The statue was supposed to be Buddha, to represent a part of my heritage, but I think it was actually a copy of a Sumerian statue that sat in one of the art studios at my university.

The real value of the drawing was the time I spent looking at myself and coming to terms with my face. I had never come across a large drawing or painting in a museum that looked like me. I hadnt even seen someone like me photographed and featured prominently in a magazine. Through drawing myself, I became familiar with the unique curves and slopes of my features, and with every stroke of charcoal over the paper, I felt as though I was stroking my own face and giving myself the love that I clearly craved. At nineteen, I was a long way from the country in which I was born, but still not quite at home in the country where I grew up. For me, home was a place to remake within myself, and part of that process was learning to love myself.

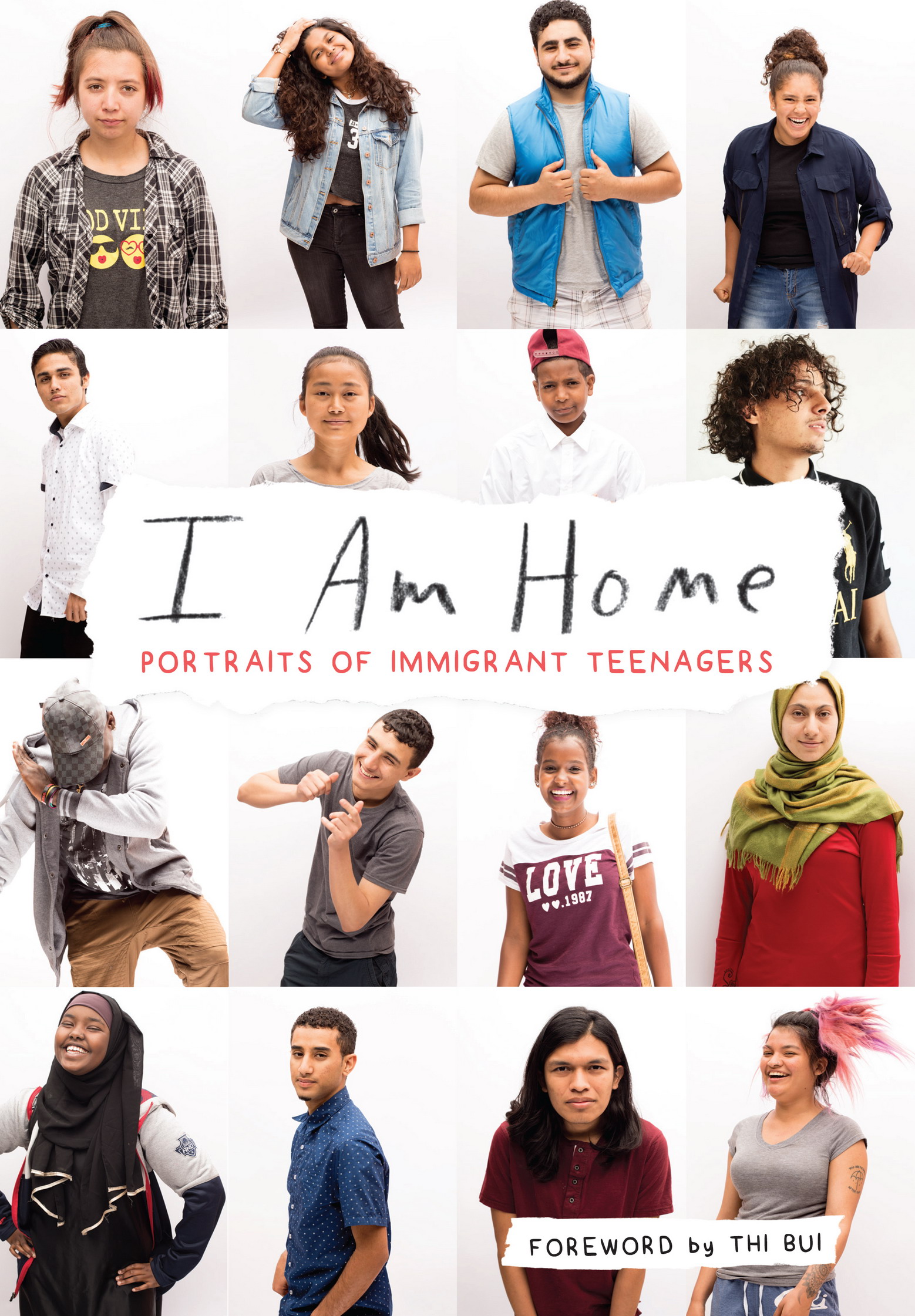

The young people in this book came to this country older than I did. They remember what their former homes looked like, how they felt, who lived there, or still lives there, and whom they miss. They have more of an original identity than I did at their age. At the same time, they are learning how to live in a new country, adopting its language, culture, and customs, changing the culture even as it changes them. Sometimes people treat them like they dont belong here. They, too, must love themselves when others wont. While their new country debates a border wall, a Muslim ban, and restricting immigration from poorer nations, they are growing home inside themselves.

Somewhere between a good photographer, a good listener, a simple backdrop, and the help of several co-conspirators, a space was created to represent this moment in their lives. And so they stand facing the camera, and this country, with grace, humor, sass, and gravitas. They expand how our imaginations visualize the words immigrant and teenager and help us see the world as it isdiverse, complicated, and much bigger than the sum of our own experiences. They challenge us to expand our notion of we and us beyond our own borders, to take in the greater experience of being a human alive on earth. They share their precious memories of a home that was and their yearning for a home to be, and in that intimacy create a space for all of us to grieve, to reflect, to hope, and to act.

Thi Bui

Berkeley, California

February 2018

Introduction

Homecoming

I am the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants from Germany, Russia, and Poland, and the daughter of New Yorkborn parents who did not speak their own parents first language. I spent my first formative years in the Northern California mountains, away from television, electricity, and other media. Though I was U.S. born, pale-skinned, and a native English speaker, when we moved to the city I was often asked, What are you? and But where are you from? Perhaps because of these experiences and perhaps because I live in a country with a long history of both stigmatizing and absorbing other cultures, Ive always been most interested in questions of belonging and homecoming.

Oakland International High School (OIHS) sits in North Oakland, just a few blocks from my childhood home, at the crossroads of a neighborhood that was once largely Asian-American and African-American and now, like many parts of Oakland, has a significant white middle-class. OIHS is one of twenty public schools in the country founded specifically to welcome immigrant teenagers from all over the world and is home to 390 students from over thirty different countries. Students have access to English as a Second Language (ESL) classes as well as a more traditional high school curriculum adapted for English learners.

Most of these teenagers have come to the United States by necessity, often leaving not just their physical homes and possessions, but their most loved ones as well. At OIHS, they have a home base, a place where they can be seen as the teenagers they areconcerned with sports, fashion, crushes, and the best selfie angles as much as with questions of navigating basic needs and trying to find a future path. Here, they do not need to constantly explain what they are or where they are from.

I first visited OIHS a number of years ago as a volunteer for their Career Day, to talk with the students about what is involved in writing, editing, and publishing books. When I asked these students how many had read a book, they all raised their hands. When I asked them how many of them had read a book that reflected their experience, only one student raised her hand. One of the books I brought to share with them was by the Zen monk Thich Nhat Hanh, who was born in Vietnam and exiled after the Vietnam War. We began talking about the idea of home and how we can carry our homes with us.

This project grew out of our conversations about what is belonging and what is home when it is, by necessity, not a physical space. Ericka McConnell shot the photographs during lunch, at recess, and after school. She shot in the courtyard and in the library, as people were milling about, shouting and playing. These are, deliberately, not formal portraits but images of these teenagers as they were most comfortable, alone or with friends. The stories alongside the portraits were taken from short interviews done in the same settings. Almost all of these interviews were conducted in English, which was none of the teenagers first language.

Thich Nhat Hanh asks, Do you have a home? You may go home each night to a house or an apartment. But do you have a true home where you feel comfortable, peaceful, and free?

He continues, Even if people occupy our country or put us in prison, we still have our true home, and they can never take it away. I speak these words to young people and to those of you who feel that you have never had a home. I speak these words to the parents, you who feel that the old country is no longer your home but that the new country is not yet your home, who see your children suffering, looking for their true home, while you have not yet found it for yourselves. A true home is what I wish for you.