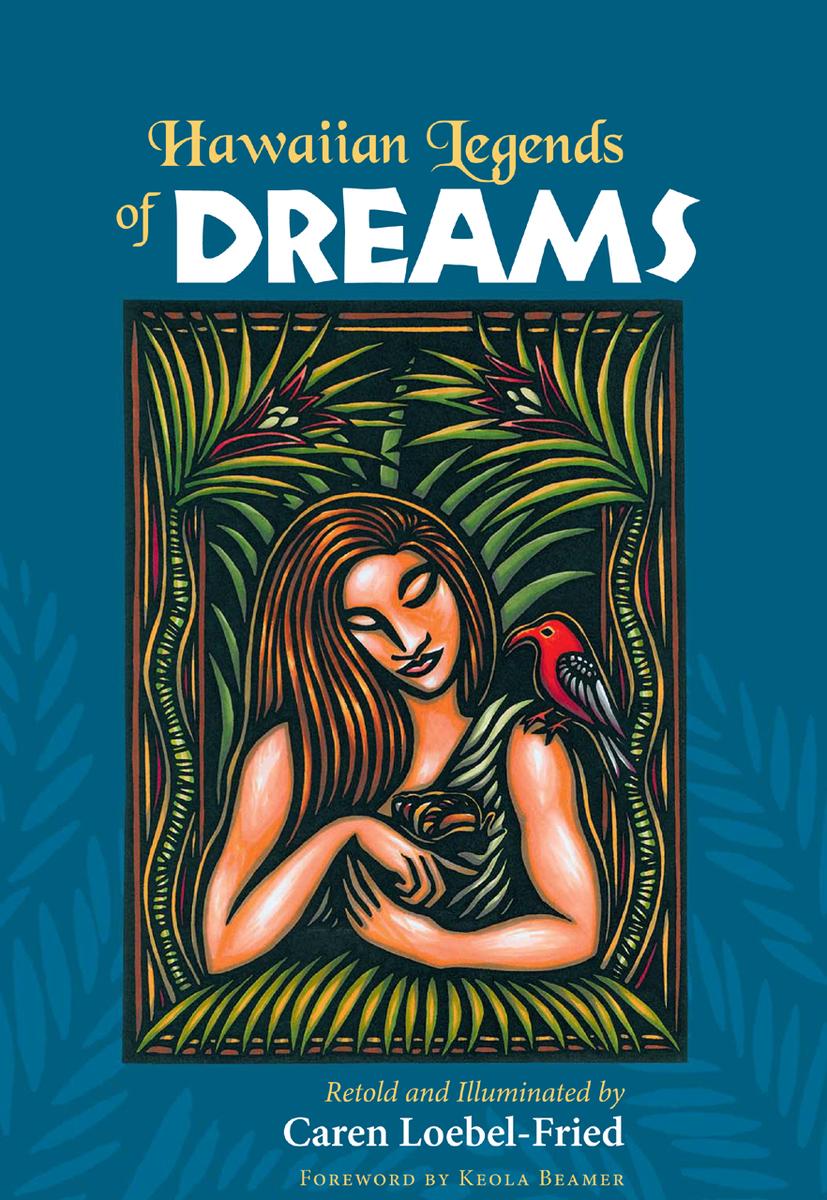

Dreams are the beginning. They are the seed of our ambitions, the source of our inspiration, and the impetus for our creations. The book you hold in your hands is the manifestation of Caren Loebel-Frieds dream to share the manao of traditional Hawaiians on the amorphous world of dreams. In this book, her love of our culture is evident in her research and beautiful art. She has captured the spirit of our view of the world, in which all things are connected and there is no distance between souls, alive or passed over, which cannot be bridged. We believe that mana, or life force, flows through the universe, and that all things have a voice even our dreams.

I want to thank Ms. Loebel-Fried for inviting me to write the foreword to this collection and for honoring my family by including our dear Sweetheart Grama (Helen Desha Beamer), who often received her songs through dreams.

xi

PREFACE

Heaha ka puana o ka moe?

What is the answer to the dream?

Pukui, lelo Noeau No. 510

Dreams have always been compelling to me. Early on I discovered that the more I worked at untangling the meaning of a dream, the more treasures it yielded. I also loved reading myths and legends, and found the legends of Hawaii to be filled with dreams. Curious about dreaming in the days of old Hawaii, I wondered what role dreams played in Hawaiian culture and how the people made use of them.

Clues came from books, some long out of print, and from unpublished manuscripts at the Bishop Museum Library and Archives. My studies on dreaming and dream symbolism in Hawaii, as well as the legends themselves, revealed the importance of dreaming in early Hawaiian life. Dreams were the principal connection between the living and the departed, the xii means by which the akua and the aumkua guided and influenced people.

This volume contains legends in which dreams play a crucial role in the story. I consulted as many versions of each legend as possible and tried to stay true to the source in my retelling. At times, the only versions that I could find were written in the Victorian era, far removed from the original oral telling. These versions were often written in a Western voice and lacked the hallmarks of an authentic Hawaiian legend. To try and offset any misrepresentations of the culture, I incorporated elements found in traditional legends. Details about daily life from archival materials were woven into the narrative, as well as place names and references to the natural elements that embody the gods and ancestors, with whom the people lived in close harmony. When a legend was very long, the retelling here focuses on the part of the story set in motion by dreams, with the best source for the full legend mentioned at the end of the story. The legends are grouped according to the kinds of dreams found within them, followed by notes intended to put the stories into the context of Hawaiian culture, nature, and history. I have also included examples of actual dream experiences of contemporary Hawaiian people, revealing that dreams continue to play an important role in Hawaiian life and are considered by many to have the same useful qualities as in the days of old.

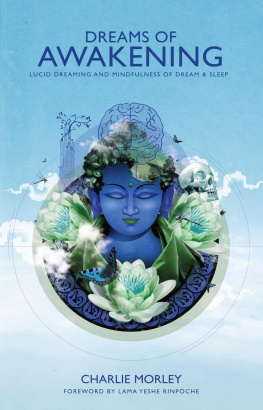

The art in this volume was created using the ancient technique of block printing, which I learned from my mother. Growing up with my mothers woodcuts covering the walls of our home, their powerful, graceful lines and designs became a part of me. My mom taught me by example, and throughout my life her art and expertise have informed my own work. More recently, while visiting an exhibit of European illuminated bibles, I was xiii riveted by the tiny color-tinted woodcuts that graced the pages of those ancient texts. I experimented with my own prints, adding color washes to some of the black-and-white designs. The results of those experiments may be seen in this book.

xv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Mahalo nui loa to Keith Leber, my editor at the University of Hawaii Press, whose patience and humor made working feel like play. I am extremely grateful to Patrice Lei Belcher, Nona Beamer, and Julie Baer, for their attention to every detail in the manuscript. Many thanks are due to B. J. Short, Ron Schaeffer, Judith Kearney, Leah Caldeira, and DeSoto Brown at the Bishop Museum Library and Archives for their wealth of knowledge and kkua. My sincere thanks to Betty Kam of the Bishop Museum for providing me with access to the special collections in the Anthropology Department. My gratitude and aloha to Keola Beamer for his support. Thanks also to Carol Holverson for her detective work in a pinch. Thanks so much to Fia Mattice, Ter Depuy, Marilyn Nicholson, and the rest of my friends at Volcano Art Center, and to Ira Ono and Aurelia Gutierrez for keeping my connection to Hawaii alive during my absences. Thanks to Alison Beddow for sharing her memories of Punahou School with me. Many thanks to Dan Sythe and Joylynn Oliveira for tracking down the elusive whale legend. I am also grateful to Kaliko Beamer-Trapp for sharing his Hawaiian language expertise. Special thanks to JoAnn Tenorio, Santos Barbasa, Lucille Aono, Paul Herr, Colins Kawai, Steven Hirashima, and William Hamilton from the University of Hawaii Press.

My love and appreciation go to my husband and son who, throughout the process, believed unfailingly in the results. My warmest thanks to my mom and Carol, xvi Helena, my Dad and Nancy, Charlie, Bette, Harriet, all of the Frieds, and to Howard Schwartz, Ilisa Singer, Maggie Harrer, Miriam Faugno, Mercedes Ingenito, and Noemie Maxwell for their enthusiastic support of this project. I am also grateful to Stuart Fried, Valerie Maxwell, Kate Whitcomb, and Virginia Wageman, whose encouragement and friendship I will always miss. Many thanks to Suzanne Parmly, my high school art teacher, an inspiring maverick who first sparked my interest in cultures different from my own.

ii

ii