Copyright 2018 by Juan Cole

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Nation Books

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003

www.nationbooks.org

@NationBooks

First Edition: October 2018

Published by Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Nation Books is a copublishing venture of the Nation Institute and Perseus Books.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cole, Juan Ricardo, author.

Title: Muhammad, prophet of peace amid the clash of empires / Juan Cole.

Description: New York : Nation Books, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018007563| ISBN 9781568587837 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781568587820 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Muhammad, Prophet, -632Biography. | IslamOrigin.

Classification: LCC BP166.5 .C65 2018 | DDC 297.6/3 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018007563

ISBNs: 978-1-56858-783-7 (hardcover); 978-1-56858-782-0 (ebook)

E3-20180827-JV-NF

Petra: rock-cut buildings. Lithograph by Louis Haghe after a painting by David Roberts, from David Roberts, The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Egypt, Nubia. Prepared by Louis Haghe. 1st ed. London: F. G. Moon, 18421849. 3 volumes.

Courtesy Library of Congress |

Angel. Ink and gold on paper. Iran, sixteenth century.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Nabataean goddess betyl.

Bjorn Anderson, University of Iowa (photograph in private collection) (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons |

Four brothers who live in Medina and who have been converted to Islam attempt to convert their pagan father. Siyar-i Nabi, Ottoman, 15941595.

Courtesy Spencer Collection, New York Public Library |

Samuel Anointing David. Silver plate for Emperor Herakleios, Constantinople, 629630.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Illustration from Futuh al-Haramayn (Opening of the Holy Cities). Muhi al-Din Lari, Bukhara, sixteenth century.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Leaf from Quran. This folio from Walters manuscript W.553 contains verses from the Surat al-araf, penned in an Early Abbasid script (Kufic) on parchment. Third century AH / AD ninth century.

Courtesy Walters Art Museum, W.553.15B |

Mecca, 1787. Pencil, ink, grey wash and watercolor. Louis Nicolas de Lespinasse, French, 17341808.

Courtesy Christies |

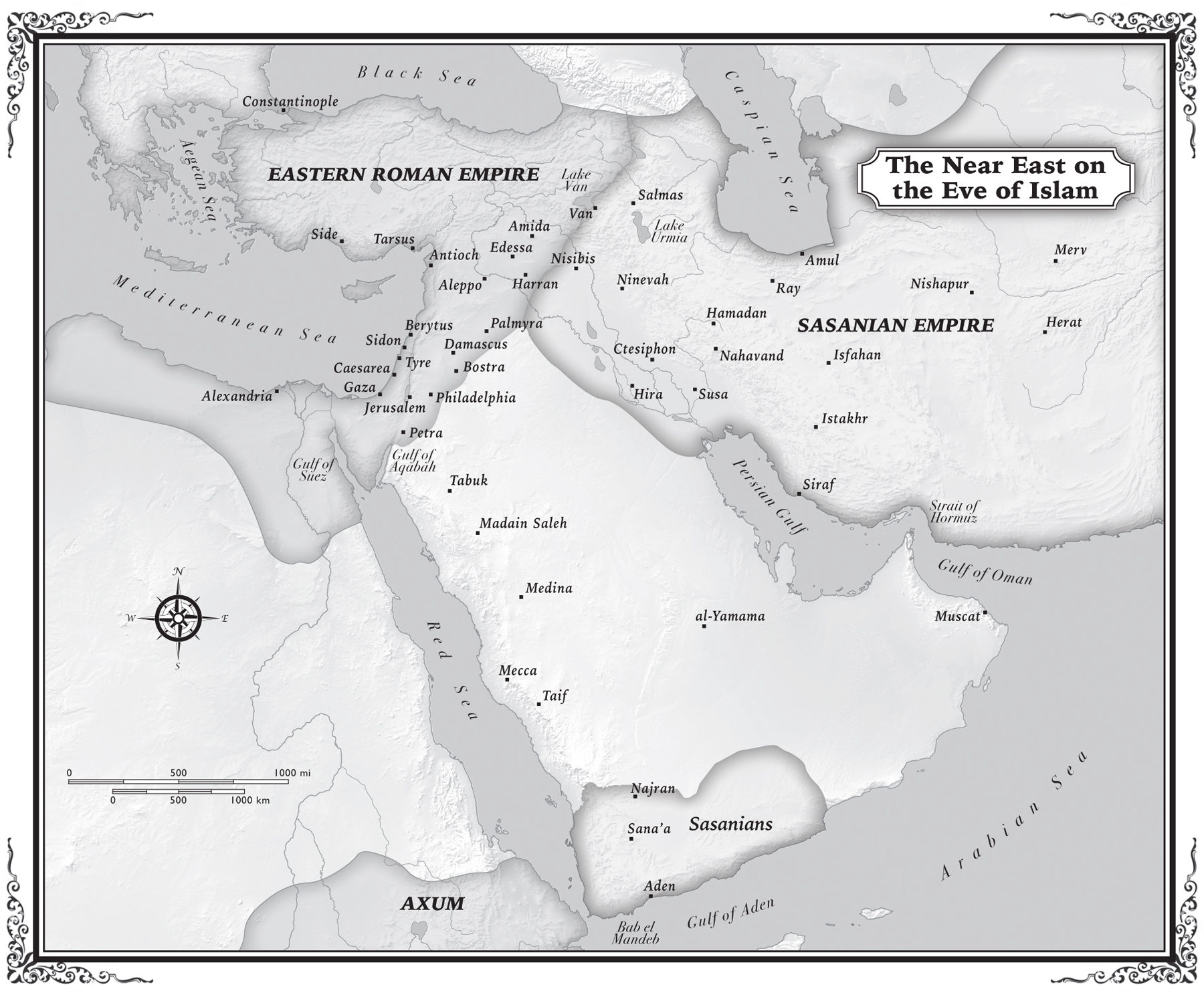

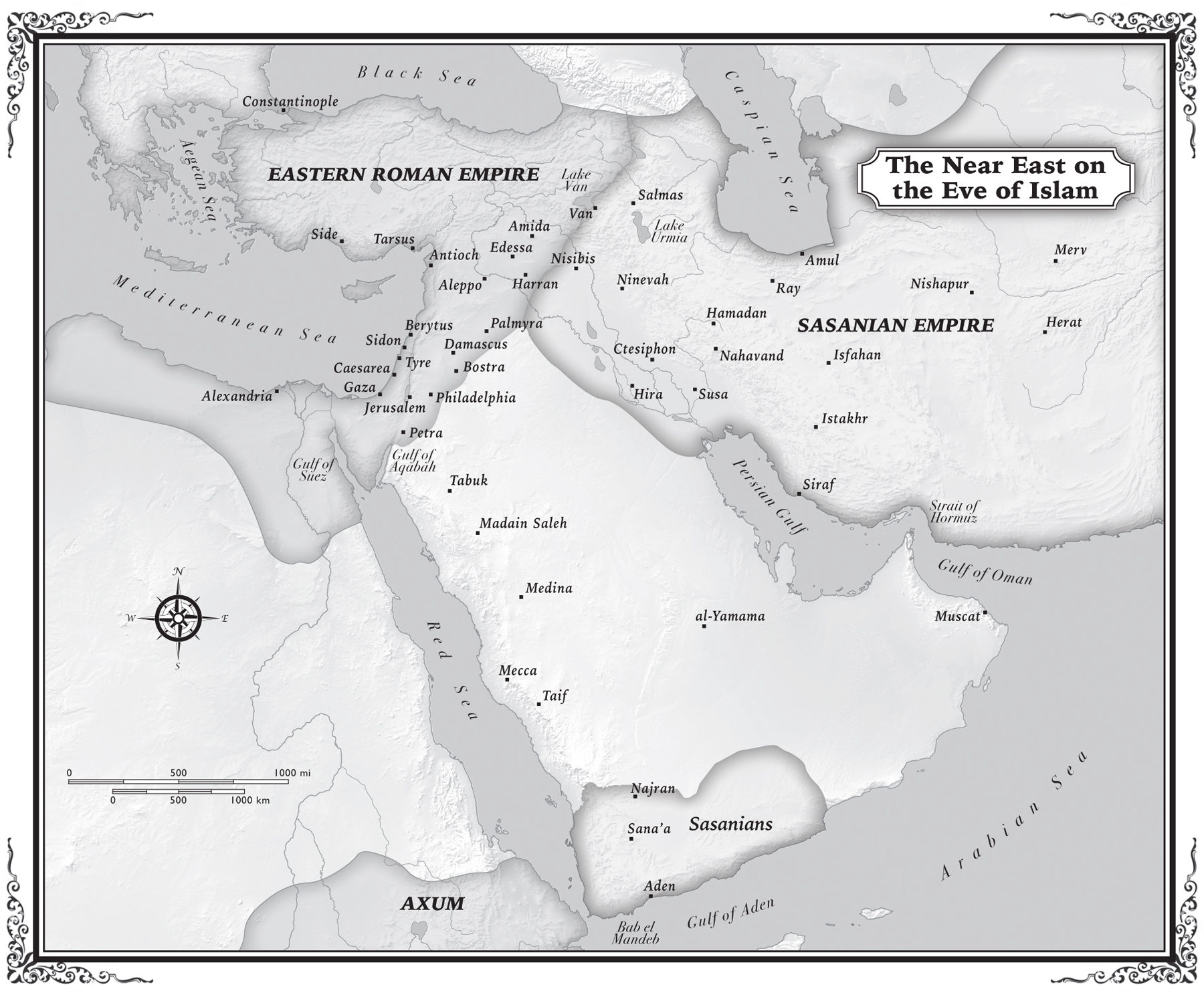

T HE NEW WORLD RELIGION OF ISLAM AROSE AGAINST THE BACKDROP of a seventh-century game of thrones between the Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Iran that was fought with unparalleled savagery for nearly three decades. The imperial armies zigzagged bloodily across the Near East, the Fertile Crescent, Asia Minor, and the Balkans. Although the Quran makes it clear that this struggle between rival emperors, whom contemporaries called the two eyes of the earth, formed an essential context for the mission of the prophet Muhammad, historians have only recently attempted explorations of the latters life and thought with this framework in mind.

This book puts forward a reinterpretation of early Islam as a movement strongly inflected with values of peacemaking that was reacting against the slaughter of the decades-long war and attendant religious strife. From the Crusades to colonialism, conflicts between Christians and Muslims led to a concentration among writers of European heritage on war and Islam, leaving the dimension of peace and cooperation neglected. Both peace and war are present in the Quran, just as they are in the Bible, and both will be analyzed below, but the focus here is on peace.

This book studies the Quran in its historical context rather than trying to explain what Muslims believe about their scripture.

The Iranian invasion of Roman territory from 603 forward threatened the independence of western Arabia, where Muhammad was based. The Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem in 614 struck contemporaries as apocalyptic and provoked a mystical response from the Prophet. A close reading of the Quran shows that a profound distress at the carnage of the age led Muhammad to spend the first half of his prophetic career (610622) imagining an alternative sort of society, one firmly grounded in practices of peace. The Quran repeatedly instructs Believers to repel evil with good, pardon their persecutors, and wish peace on those who harassed them. These verses have as their greater context the outbreak of struggles among Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and a remnant of pagans, who were partisans in the clash of empires raging around them. Muhammad in these years resembles much more the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount than is usually admitted.

Scholars have increasingly also tied the second half of Muhammads career, 622632, to the maneuverings of Rome and Iran, even suggesting that his move to Medina from his hometown of Mecca may have been connected to Roman diplomacy.emperor Herakleios (r. 610641) and indeed that Muhammad saw his defensive battles against truculent pagans in places such as Badr and Uhud in West Arabia as protecting Roman churches in Transjordan and Syria, to the north. It is likely these militant Arabian pagans had allied with the Iranian king of kings.

In short, Islam is, no less than Christianity, a Western religion that initially grew up in the Roman Empire. Moreover, Muhammad saw himself as an ally of the West. The Prophet in those years of pagan attacks did not abandon his option for peace but moved toward a doctrine of just war similar to that of Cicero and late-antique Christian thinkers. He repeatedly sued for peace with a bellicose Mecca, but when that failed he organized Medina for self-defense in the face of a determined pagan foe. The Quran insists that aggressive warfare is wrong and that if the enemy seeks an armistice, Muslims are bound to accept the entreaty. This disallowing of aggressive war and search for a resolution even in the midst of violent conflict justifies the title prophet of peace, even if Muhammad was occasionally forced into a defensive campaign. The Quran contains a doctrine of just war but not of holy war and does not use the word jihad with that latter connotation. It views war as an unfortunate necessity when innocents, and the freedom of conscience, are threatened. It strictly forbids vigilantism and equates premeditated killing of noncombatants with genocide, paraphrasing in this regard Jewish commentaries on the Bible in the Jerusalem Talmud.

The Quran, read judiciously alongside later histories, suggests that during Muhammads lifetime, Islam spread peacefully in the major cities of Western Arabia. The soft power of the Qurans spiritual message has typically been underestimated in most treatments of this period. The image of Muhammad and very early Islam that emerges from a careful reading of the Quran on peace-related themes contradicts not only widely held Western views but even much of the