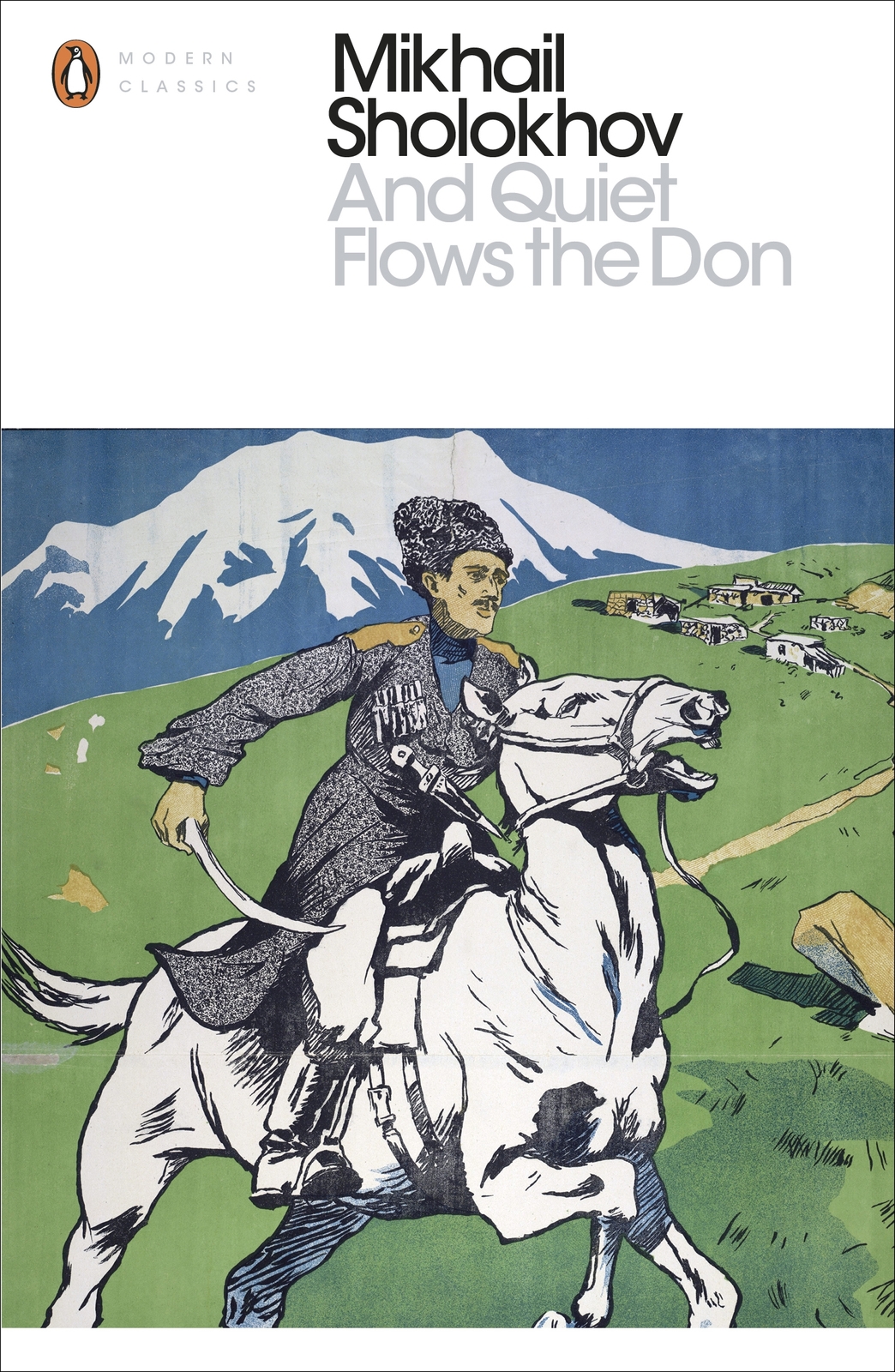

Mikhail Sholokhov - And Quiet Flows the Don

Here you can read online Mikhail Sholokhov - And Quiet Flows the Don full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:And Quiet Flows the Don

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

And Quiet Flows the Don: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "And Quiet Flows the Don" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

And Quiet Flows the Don — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "And Quiet Flows the Don" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov (19051984) was born in Russia in the land of the Cossacks. During the Russian civil war he fought on the side of the revolutionaries, and in 1922 he moved to Moscow to become a journalist. In 1926, Sholokhov began writing And Quiet Flows the Don, and he published the first volume in 1928. Three more volumes followed with the last one published in 1940. In 1965 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for the artistic power and integrity with which, in his epic of the Don, he has given expression to a historic phase in the life of the Russian people.

The Melekhov farm was right at the end of Tatarsk village. The gate of the cattle-yard opened northward towards the Don. A steep, sixty-foot slope between chalky, grassgrown banks, and there was the shore. A pearly drift of mussel-shells, a grey, broken edging of shingle, and then the steely-blue, rippling surface of the Don, seething beneath the wind. To the east, beyond the willow-wattle fence of the threshing-floor, was the Hetmans highway, greyish wormwood scrub, vivid brown, hoof-trodden knotgrass, a shrine standing at the fork of the road, and then the steppe, enveloped in a shifting mirage. To the south a chalky range of hills. On the west the street, crossing the square and running towards the leas.

The cossack Prokoffey Melekhov returned to the village during the last war with Turkey. He brought back a wife a little woman wrapped from head to foot in a shawl. She kept her face covered, and rarely revealed her yearning eyes. The silken shawl was redolent of strange, aromatic perfumes; its rainbow-hued patterns aroused the jealousy of the peasant women. The captive Turkish woman did not get on well with Prokoffeys relations, and ere long old Melekhov gave his son his portion. The old man never got over the disgrace of the separation, and all his life he refused to set foot inside his sons hut.

Prokoffey speedily made shift for himself; carpenters built him a hut, he himself fenced in the cattle-yard, and in the early autumn he took his bowed, foreign wife to her new home. He walked with her through the village, behind the cart laden with their worldly goods. Everybody from the oldest to the youngest rushed into the street. The cossacks laughed discreetly into their beards, the women passed vociferous remarks to one another, a swarm of unwashed cossack lads called after Prokoffey. But, with overcoat unbuttoned, he walked slowly along as though over newly ploughed furrows, squeezing his wifes fragile wrist in his own enormous swarthy palm, defiantly bearing his lint-white, unkempt head. Only the wens below his cheekbones swelled and quivered, and the sweat stood out between his stony brows.

Thenceforth he went but rarely into the village, and was never to be seen even at the market. He lived a secluded life in his solitary hut by the Don. Strange stories began to be told of him in the village. The boys who pastured the calves beyond the meadow-road declared that of an evening, as the light was dying, they had seen Prokoffey carrying his wife in his arms as far as the Tartar mound. He would seat her, with her back to an ancient, weatherbeaten, porous rock, on the crest of the mound; he would sit down at her side, and they would gaze fixedly across the steppe. They would gaze until the sunset had faded, and then Prokoffey would wrap his wife in his coat and carry her back home. The village was lost in conjecture, seeking an explanation for such astonishing behaviour. The women gossiped so much that they had no time to hunt for their fleas. Rumour was rife about Prokoffeys wife also; some declared that she was of entrancing beauty; others maintained the contrary. The matter was set at rest when one of the most venturesome of the women, the soldiers wife Maura, ran along to Prokoffey on the pretext of getting some leaven; Prokoffey crawled into the cellar for the leaven, and Maura had time to notice that Prokoffeys Turkish conquest was a perfect fright.

A few minutes later Maura, her face flushed and her kerchief awry, was entertaining a crowd of women in a by-lane:

And what could he have seen in her, my dears? If shed only been a woman now, but shes got no bottom or belly; its a disgrace. Weve got better-looking girls going begging for a husband. You could cut through her waist, shes just like a wasp. Little eyes, black and strong, she flashes with them like Satan, God forgive me. She must be near her time, Gods truth.

Near her time? the women marvelled.

Im no babe! Ive reared three myself.

But whats her face like?

Her face? Yellow. Unhappy eyes its no easy life for a woman in a strange land. And what is more, women, she wears Prokoffeys trousers!

No! the women drew their breath in abrupt alarm.

I saw them myself; she wears trousers, only without stripes. It must be his everyday trousers she has. She wears a long shift, and below it you see the trousers, stuffed into socks. When I saw them my blood ran cold.

The whisper went round the village that Prokoffeys wife was a witch. Astakhovs daughter-in-law (the Astakhovs lived in the hut next to Prokoffeys) swore that on the second day of Trinity, before dawn, she saw Prokoffeys wife, straight-haired and barefoot, milking the Astakhovs cow. From that day the cows udder withered to the size of a childs fist, she gave no more milk and died soon after.

That year there was unusual mortality among the cattle. By the shallows of the Don the carcasses of cows and young bulls littered the sandy shore every day. Then the horses were affected. The droves grazing on the village pasture-lands melted away. And through the lanes and streets of the village crept an evil rumour.

The cossacks held a village meeting and went to Prokoffey. He came out on to the steps of his hut and bowed.

What good does your visit bring, worthy elders? he asked.

Dumbly silent, the crowd drew nearer to the steps. One drunken old man was the first to cry:

Drag your witch out here! Were going to try her

Prokoffey flung himself back into the hut, but they caught him in the porch. A sturdy cossack nicknamed Lushnia knocked Prokoffeys head against the wall and exhorted him:

Dont make a sound, not a sound, youre all right. We shant touch you, but were going to trample your wife into the ground. Better to destroy her than have all the village die for want of cattle. But dont you make a sound, or Ill smash your head against the wall!

Drag the bitch into the yard! came a roar from the steps. A regimental comrade of Prokoffeys wound the Turkish womans hair around one hand, pressed his other hand over her screaming mouth, dragged her at a run through the porch and flung her beneath the feet of the crowd. A thin shriek rose above the howl of voices. Prokoffey sent half a dozen cossacks flying, burst into the hut, and snatched a sabre from the wall. Jostling against one another, the cossacks rushed out of the porch. Swinging the gleaming whistling sabre around his head, Prokoffey ran down the steps. The crowd shuddered and scattered over the yard.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «And Quiet Flows the Don»

Look at similar books to And Quiet Flows the Don. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book And Quiet Flows the Don and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.