Contents

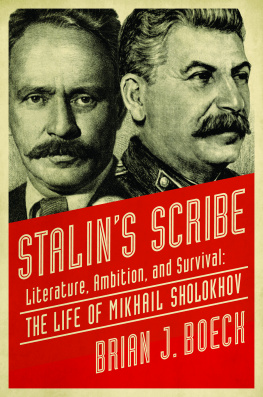

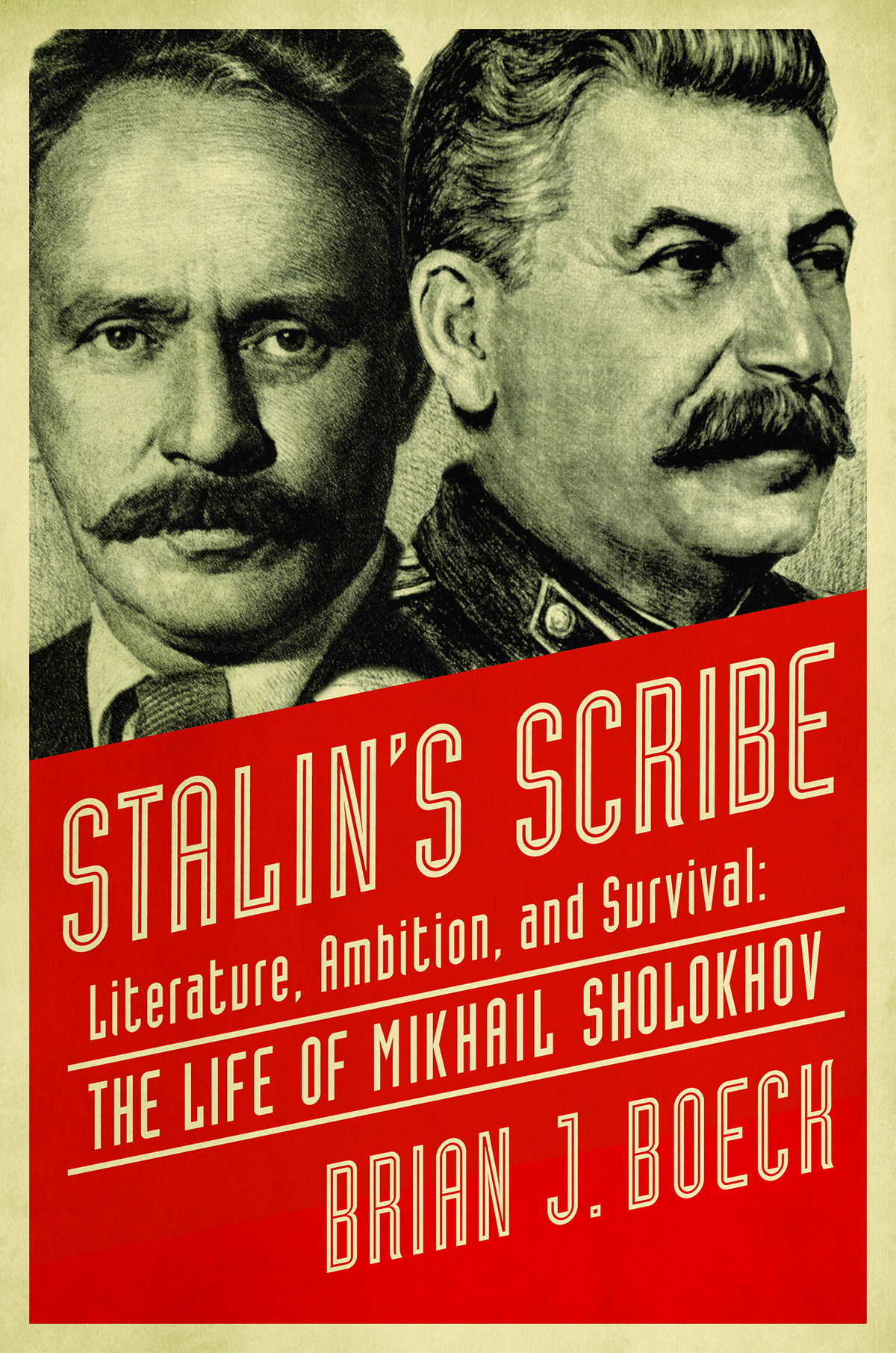

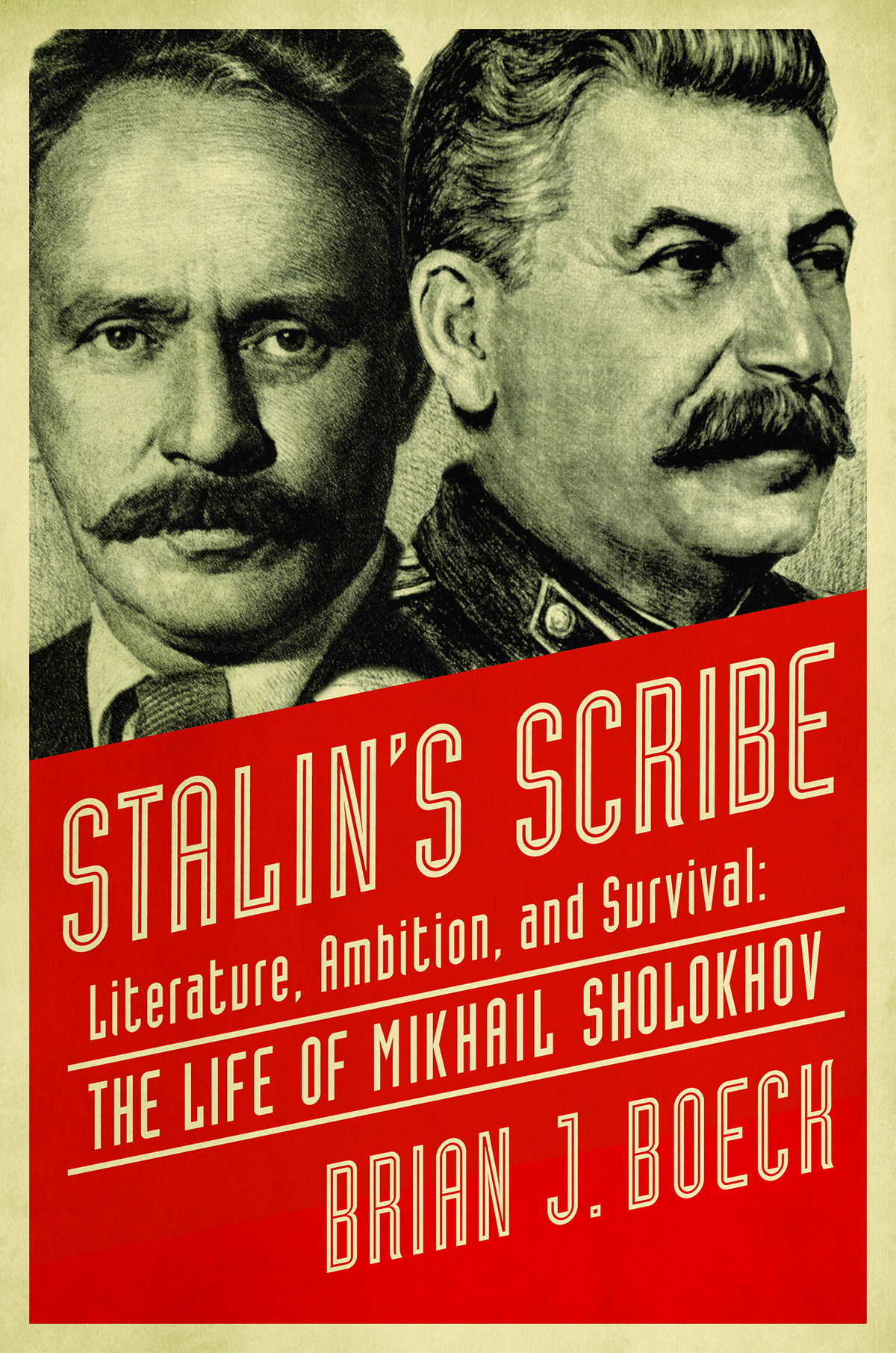

STALINS SCRIBE

LITERATURE, AMBITION, AND SURVIVAL:

THE LIFE OF MIKHAIL SHOLOKHOV

BRIAN J. BOECK

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

STALINS SCRIBE

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Brian Boeck

First Pegasus Books edition February 2019

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without

written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in

connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any

part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or

by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written

permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-874-7

ISBN: 978-1-68177-939-3 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

Dedicated to the past and present librarians of Guadalupe County, Texas.

A NOTE ON TRANSLATIONS, TERMINOLOGY, AND SOURCES

A ll translations presented here are my own. Where possible I have strived to distinguish between informal and official registers and to convey a sense of the tone and tenor of Soviet discourse. Since the translation process always involves a number of interpretive decisions and judgement calls I have erred on the side of making the text accessible to the widest possible audience. In a small number of cases I have deployed more easily understood or informal terms rather than the more formal official versions and their variations. The title of party secretary, which conveyed a great deal of power and prestige in the USSR, presents a particular problem due to the connotations of the term in English. The fact that Stalin was a secretary too, should leave no doubts about its high status connotations. For continuity I have used a single recognizable political term, Politburo, rather than the other names for entities which served the same or similar functions at different times. Though Sholokhovs epic novel is known in some English translations as And Quiet Flows the Don, I have opted for Quiet Don because it is closer to the original, which refers to both a quietly flowing body of water and the poetic personification of the river, Don Ivanovich, in Cossack folklore. Publishers in England added specificity to the title in order to avoid any suggestion that the book was about the life of a taciturn fellow at Oxford, a different kind of don altogether.

In a limited number of cases I have utilized oral or visual sources that do not easily lend themselves to citation. A number of aphorisms, turns of phrase, and anecdotes about Soviet history derive from my travels in Russia over the course of two decades. Visual descriptions of places rely partly on photographs and partly on my own experiences. For descriptions of people and historical interiors I have consulted photographic evidence that is close in time to either the person or event described. Illustrations 14 render historical photographs that were not available for publication. Only the first image would have been widely known to the Soviet public.

In order to reconstruct events as Sholokhov saw them, I have critically scrutinized the reminiscences of his friends, relatives, and assistants. Their accounts are often partial, protective, and chronologically imprecise. Nonetheless, they provide important insights into his mindset and key testimonies about how he narrated the story of his encounters with Stalin and other Soviet leaders. The dialogues presented here can be read both as vivid recollections of important meetings and as revealing reflections of Sholokhovs ongoing personal dialogue with the process of de-Stalinization. His strategic recall of aspects of his relationship with the dictator frequently responded to current Soviet controversies and political trends. A systematic reading of Pravda, Izvestiia, and Literaturnaia Gazeta for the period of Sholokhovs biography helped me to picture Sholokhov as a man of his time and avoid presentist biases of every imaginable variety.

PREFACE

T his meeting was his only hope. A young man in a drab military tunic maneuvered his way through throngs of pedestrians. He was rushing to the most important encounter of his life. On that summer day in 1931 few could have guessed that this blond, baby-faced youth with a bashful, yet cunning, smile was Mikhail Sholokhov, the rising star of Russian literature. The twenty-six-year-old approached a mansion in the heart of Moscow with a mix of trepidation and forced bravado. His heart pounded as he reached the ornate gate.

This was the home of Russias most famous living writer. By pleading with Maxim Gorky, Sholokhov hoped to save Quiet Don, the Soviet Unions epic equivalent of Gone with the Wind. The unfinished novel had already won him fame, controversy, acclaim, and envy. Bureaucrats had banned the latest installment as anti-Soviet. As he stepped inside the mansion, darkness confronted him. A rapid succession of footsteps brought him into a surreal space bathed in multicolored swatches of light emitted from stained-glass panels above. More darkness brought him to two tall, exceedingly imposing doors. As the doors opened, he could see a backlit silhouette at the end of a long, rectangular table. A lamp illuminated an astonishing profile and a bushy mustache. This was decidedly not the familiar silhouette of Gorky. The mustache belonged to a face made famous by newspaper engravings and grainy black-and-white photos of May Day parades.

That evening Joseph Stalin decided to discuss characters and scenes in Quiet Don rather than unravel conspiracies or analyze grain reports. Following introductions, Gorky receded into the background. Stalin beckoned Sholokhov to approach. In seconds it became clear that this was no social call. Stalin immediately accused Sholokhov of sympathizing with some of the revolutions most vicious adversaries. Resorting to one of his favorite tactics, he advanced a series of damning allegations. These were calculated to knock his adversary off balance and unmask his true character. Would his target retreat? Would he submit and become subservient? Or would he push back?

Sholokhov saw the dictators eyes burning like those of a tiger ready to pounce. The snap decision he made in that instant had the potential to either influence his life for decades or to end it. He stood his ground. With his career on the line, he confidently argued with Stalin and vigorously defended his audacious decision to write sympathetically about the Cossacks, the former tsarist military caste that rose in rebellion against the Soviet government.

Stalin was impressed by Sholokhovs tenacity. Concluding his barrage of questions, he started to reminisce about his first, albeit temporary, taste of dictatorship in 1918. In Tsaritsynthe industrial city on the Volga River that had recently been renamed Stalingrad in his honorStalin had encountered several Cossacks who now reminded him of characters in Quiet Don. The dictator and the writer bonded over conversations about battles that had faded from public memory but would soon become central to the emerging Stalin cult. Elated, Sholokhov departed from the mansion with the most coveted prize in the USSRStalins personal telephone number. Though fate had smiled upon him that evening, he soon discovered that a dictators favor comes with daily dangers and crushing burdens. As Stalins prized protg, he would have to become a new man.