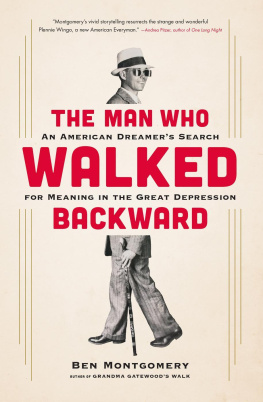

Copyright 2018 by Ben Montgomery

Cover copyright 2018 by Hachette Book Group

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown Spark

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrownspark.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany/

First Edition: September 2018

Little Brown Spark is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown Spark name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-43804-9

E3-20180824-DA-PC

Table of Contents

Navigation

For John Burruss

Never mind how far he got.

What it is, is the tilt of the hat.

Dodie Messer Meeks

Dear reader,

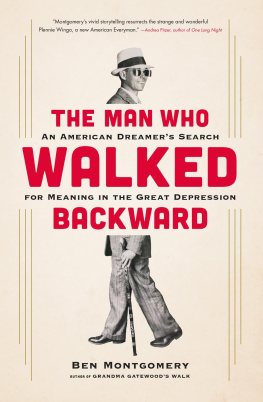

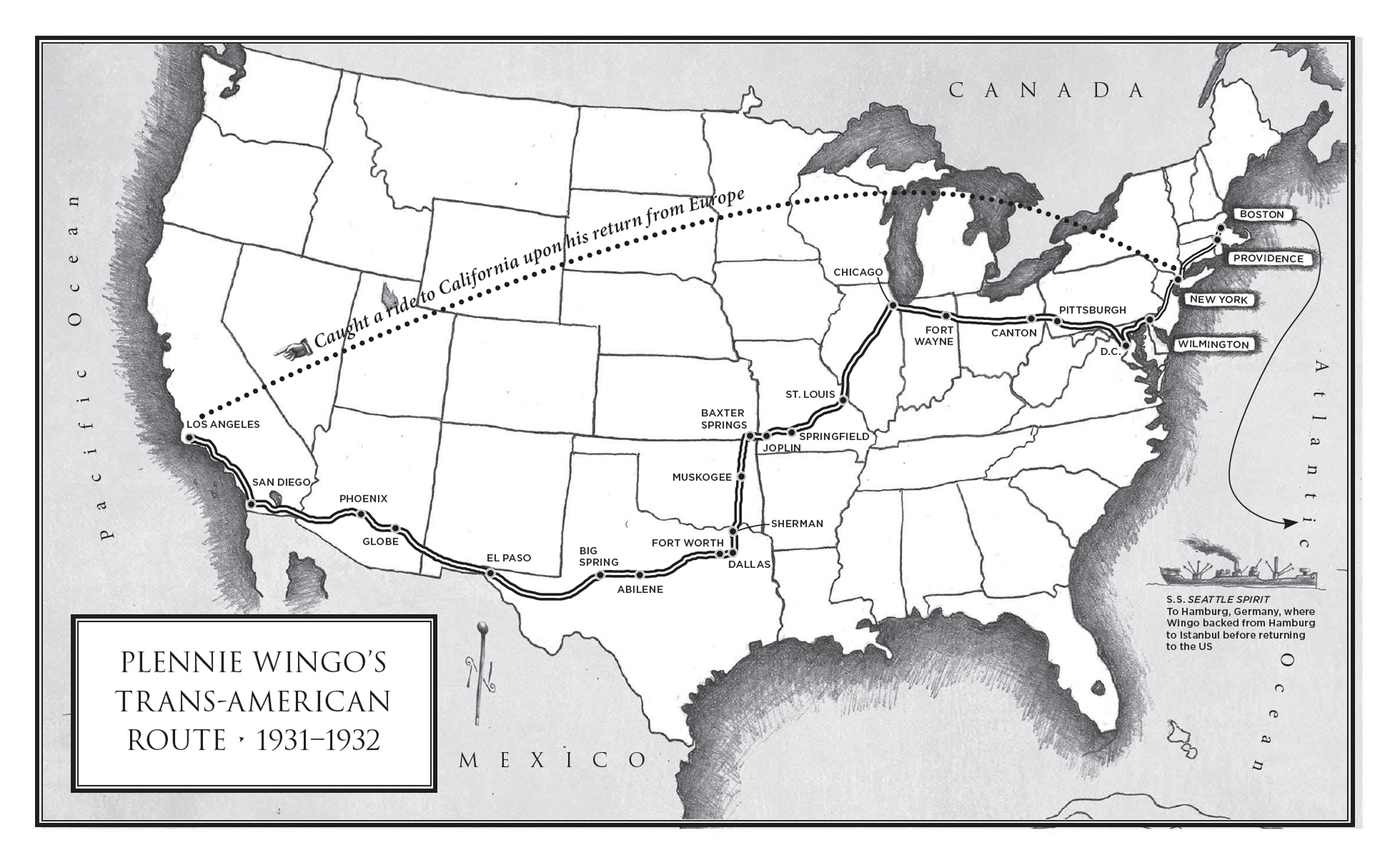

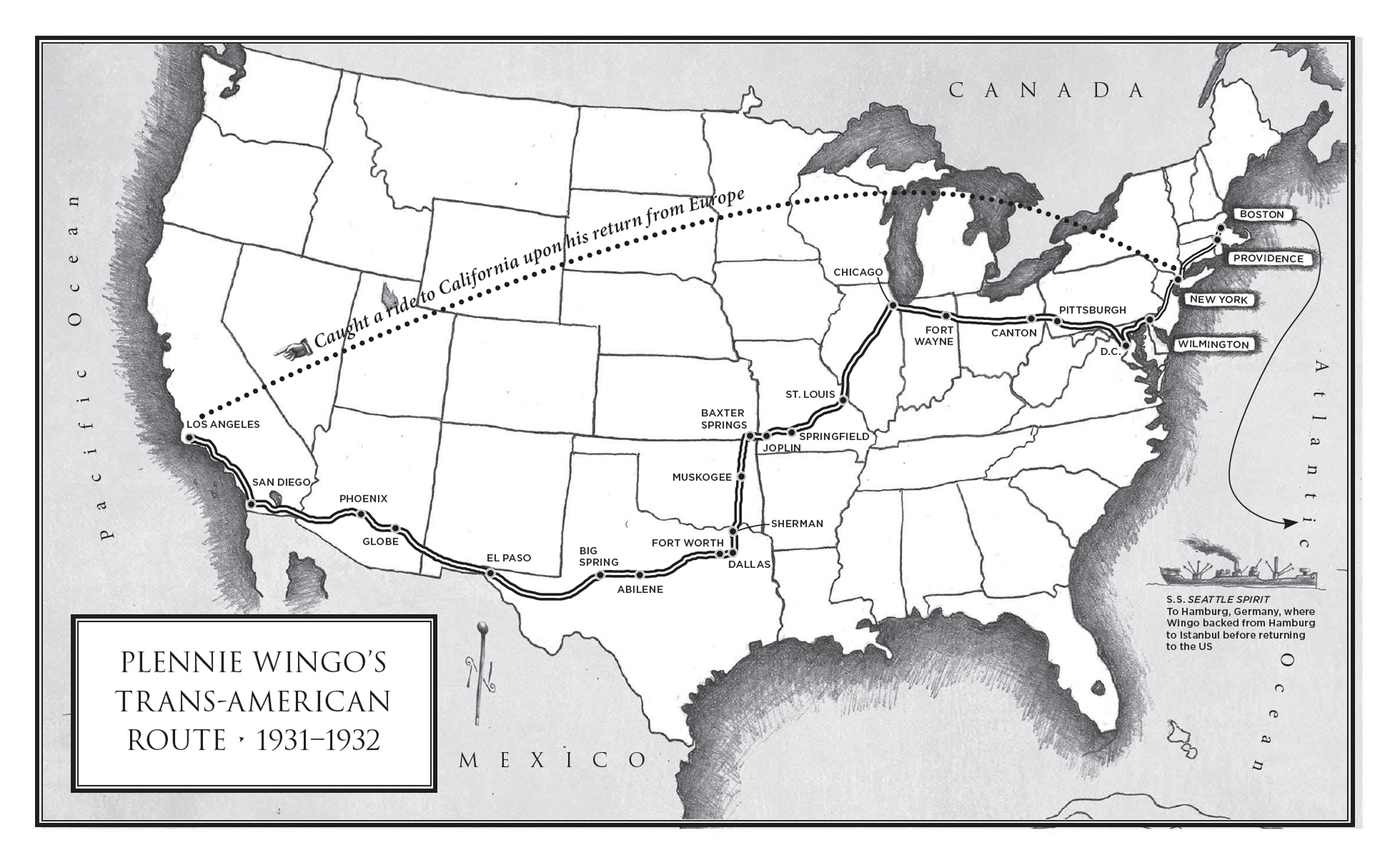

Plennie Wingo died in poverty in the fall of 1993. He was buried in Wichita Falls, Texas, about 180 miles from my hometown of Slick, Oklahoma. I first heard of him in 2013 while researching unconventional pedestrians. A few years later, when I could not forget him, I decided to try to write a book. The first thing I did was buy a Clasons Touring Atlas, circa 1931, one of the first ever made, so I could follow in his footsteps to see what he mightve seen, and to see how weve changed. One note about change: to avoid littering the text with calculations, Ive left it to you, dear reader, to put dollar amounts into familiar context. So, $1 in 1931 is equal to roughly $16 in 2018; $5 then is $80 now; $10 is $160; and so on.

Ive tried my best to tell his story true. Nothing in this book is fabricated by me, including the dialogue. If its in quotes, it comes from a historic document or Plennie Wingos own humble account of his trip. Ive tried to tell the story of that dark period true, as well. For that reason, and because we are occasionally mean to one another, you should be aware that this book depicts quite a bit of violence.

Thank you for reading,

Ben

S unrise, West Texas.

Time of morning when the dead black gives up to the first throws of yellowpink in the east, out beyond Fort Worth and Dallas, past Shreveport and Jackson and Montgomery and Savannah. A man here in Abilene walks this morning, like every morning, down a bone-dry farm-to-market road outside town. He is out before the sun because he walks backward, that is to say, he walks in reverse, and he chooses this time so he may behave in this odd fashion cloaked in darkness lest his neighbors see and cast judgment upon him, make him for crazy. His own mind is fairly certain on the point, but hell admit there is room for doubt.

He is not a brilliant man. Some would say he does not even encroach on smart. But inside his balding head he has a bold idea, and sometimes when a certain kind of man has a certain kind of idea, one that he considers good, that good idea takes hold of him and it swells up behind his eyeballs and expands, balloonlike, so big that it crowds out all the other thoughts and ideas, and it becomes the one thing he thinks about, the only thing. Such is the case with Plennie Lawrence Wingo, who is nearly penniless but full of ambition just shy of his thirty-sixth birthday and a hair short of what would be one of the worst years in American history.

The idea has become an obsession, though hes not ready to admit that just yet. He thinks of it when he wakes in the morning and it follows him all day long, and when he closes his eyes at night he is wrapped completely in the blanket of his vision.

The idea is why he walks. It is why he walks backward.

Five miles some mornings. Ten, others. Hours alone in the last gasp of night, scooting retrograde across the long shadows drawn on the dawning landscape, the place they called the Great American Desert, Llano Estacado, past the roadside tufts of buffalo grass and thickets of honey mesquite, the reaching lechuguilla rods and smoke bush and angry explosions of butterfly weed. Backward across the land from which they pulled oil until that went bust; the land upon which, before the oil, they raised cattle until that too went bust; the land from which, before the oil and the cattle, they harvested buffalo bones, full skulls and skeletons that once gave shape to the great roaming beasts of the Plains, the givers of tools and food and warmth for the natives, and, after them, fertilizer for the white men in sweat-stained cowboy hats who stacked their bones like cordwood, building white hills head-high and as far as you could see. The bones brought twelve to fifteen dollars a ton to any man resourceful enough to pile them high, and they were plentiful in Abilene, the epicenter of this macabre market for three hundred miles in most directions. They took the bones, then the beasts, then the oil beneath, and then it was all gone. What was next for the taking was anyones guess. What else was left?

Now the town near which he walks holds abundant life, or at least enough to advertise to the outside world. The rising sun in the east outlines its elegant business structures and its beautiful, commodious homes, its apartment houses with up-to-date Frigidaire refrigeration, its magnificent public buildings and institutions like the Abilene State Hospital for Epileptics and Simmons College, its model school buildings, three now, its federal post office and courthouse, its compress, its oil mill, its electric light plant, its ice factory, its impressive fairgrounds, its artificial lake, its parks, its paved boulevards, its railways, and, pitched against the weak sunlight, its Paramount Theatre, built this very year, 1930, its grandeur unrivaled between El Paso and Fort Worth. To think that so much had sprung forth from nothing but dry Texas dirt in just fifty years.

That same dry dirt chalks his teeth and cakes his forehead, and his garments show signs of a man who has put in a full days work by the time most are beginning to wipe sleep from their eyes, drag on their trousers, and start the percolator. He thinks about them, how theyd whisper if they ever caught sight of him out here, all alone and going backward. How theyd wonder what he was up to, what kind of crazy had gotten hold of him. They would, of course, ask him, Why? Over and over again, Why are you doing this? Even now, he is formulating his response.

He has not known a full days work in some time. Theyd talk about that, too, for sure. How his lot had soured. How theyd read about his troubles with the police in the paper. Another reason he is here, backpedaling in the dawn.

He hoped theyd remember the good times and his good name. Hed experienced high days, sure, when his future seemed full of promise. He was a man of business for a time, resourceful, straight as a preacher on Sunday.