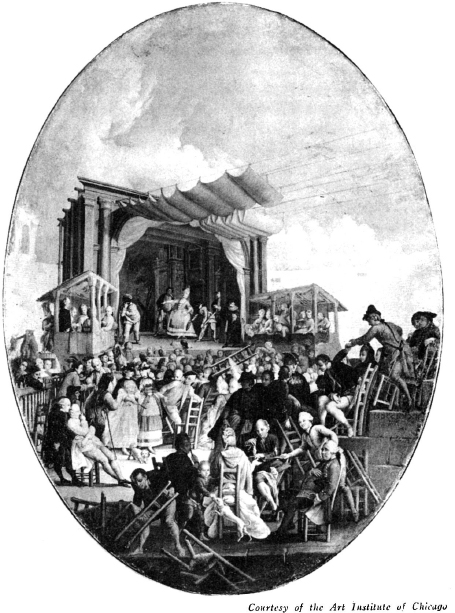

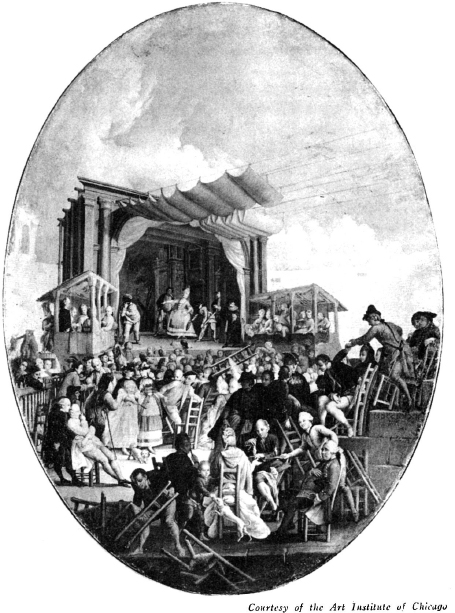

Cummedia dell Arte Performance in the Arena at Verona.

Marco Marcolas Oil Painting (1772).

A SOURCE BOOK

in

THEATRICAL HISTORY

(SOURCES OF THEATRICAL HISTORY)

By

A. M. NAGLER

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

Copyright 1952 by A. M. Nagler.

All rights reserved.

This Dover edition, first published in 1959, is an unabridged, unaltered republication of the First Edition formerly titled Sources of Theatrical History. The publishers are grateful to Miss Blanche Corin of Theater Annual, Inc. for her cooperation.

Standard Book Number: 486-20515-0

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 58-59789

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

20515029

www.doverpublications.com

To

MY FATHER

and the memory

of

MY MOTHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The sections by Constantin Stanislavsky on pages 586 to 589 are from My Life in Art published by Theatre Arts Books, New York, reprinted by their permission. Copyright 1924 by Little Brown & Co., Copyright 1948 by Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood, Attorney-in-fact for the Stanislavsky Estate.

The sections by August Strindberg on pages 583 to 586 are from Plays by August Strindberg: Miss Julia, The Stronger with the Authors Preface. Translated from the Swedish with an Introduction by Edwin Bjorkmann. Copyright 1912 by Charles Scribners Sons; copyright renewal 1940 by Edwin Bjorkmann. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

PREFACE

The theater historian is expected to reconstruct, both vividly and accurately, the conditions under which the plays of Sophocles, Corneille, Calderon, Lyly, Goldoni, Hebbel, or Gorky were first performed. And yet the very essence of the theater is absolute transitoriness. Scene designs, if not lost, are preserved only in the artists original drawings which cannot be accepted as conclusive evidence as to the sets appearance on the stage; if a print of the actual set is preserved, it cannot faithfully convey the ephemeral impression made on contemporary audiences. Theater history deals with costumes that were burnt, with playhouses that have perished, with actors who made their final exits 2,500 years ago, with chandeliers that can be lit no more, and with audiences that have vanished. The theater historians task approximates most closely that of the archaeologist, but he must also have at his command the methods of the art historian and the sociologist. He has to say something pertinent about a work of art which, being spatial and temporal, existed when he was not around to behold it. He finds himself in the unenviable position of the art historian who plans to evaluate the lost paintings of Polygnotus and Zeuxis.

Evidently, here is the point where the study of the sources of theatrical history comes in, the poring over scholia, letters, archival statistics, eyewitness accounts, prefaces, reviews, drawings, prints, etc. sources, by the way, of very unequal value. For even today, when a performance is recorded in a dozen daily papers by either raving reviewers or post-mortem examiners, it is extremely difficult to point out enough objective material that will satisfy the ever-questioning scholar who may a hundred years hence attempt an authentic reconstruction of todays stage.

The word stage is used advisedly, for the documents crowded into the space of Sources of Theatrical History are removed from the drama as a form of literary expression. Here is a purely theatrical anthology, from the Greeks to the end of the nineteenth century (just before, thanks to Appia, Craig, and Reinhardt, things began to look brighter again in the theater), which has been assembled in the hope that a collection of primary sources will be a welcome tool for students of theatrical history. As survey courses have their limits, so this collection has had to be confined to certain climaxes in the development of the various national theaters. Many such volumes would have to be filled if a claim to completeness were to be made.

Here the student of the theater will find documents that are as well known as the Fortune contract or as Hazlitts pen portraits of Keans Gloucester, but also such recondite ones as the Bios Aischylou or the Mercures description of Servandonis sets. Some among the three hundred selections appear in English for the first time. Each excerpt is preceded by an introduction which serves to establish the chronology and to set the scene for the entrance of the source itself.

The playgoer will watch the metamorphoses of Thespis with fascination; under the guidance of an academician, he will participate in a Renaissance revival of Oedipus Rex in the Teatro Olimpico, or witness, through the eyes of a Venetian diplomat, a masque performance at the court of James I, or enter, with Washington Irving, the first Park Theater in New York. Wherever he opens the volume, the theater of the past, with its period flavor, will come to life, and he will be bound to concede that the theater historian is not a person who has ceased to feel as a playgoer, but one who is amply rewarded when he can share the transient emotional experiences of former generations of spectators.

With only a few exceptions, the spelling and punctuation of the original sources have been faithfully preserved. Some obvious misprints, however, have been corrected.

It remains for me to express my gratitude to Miss Blanche A. Corin whose imagination turned what was a manuscript into a book, the pages of which make smoother reading thanks to her editorial criticism.

A.M.N.

Yale University

Easter, 1952

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

The idea of collecting materials for a history of the theater is part of our classical heritage. The earliest attempt dates back to the time of Augustus, when Juba II, King of Mauretania, compiled his seventeen-book theatrik historia. The greatest single blow sustained by our field of learning is the loss of Jubas work.

Theatrical history was an avocation for Juba II, on whom his contemporaries bestowed the honorific epithet historictatos, signifying that he was the most historical-minded of all kings. By profession he was a statesman and a politician. Educated in Rome, he evidently learned how to meet influential people, for he accompanied Octavian on his sundry expeditions and married a daughter of Antony. On his return to Africa, he transformed the ancient Carthaginian seaport of Iol into a center of Hellenistic culture, while devoting himself to historical studies ranging from the geography of the Orient to the corruption of language. We may safely assume that he had a complete research staff working for him.

When King Juba was compiling his theatrical history, he had access to the primary sources of Greek and Roman stage practice. He must have had before him all pertinent source material, the disappearance of which is responsible for our groping in the dark when we try to investigate the theater of antiquity. Juba must have read Agatharchus own commentary on the design work he had done for Aeschylus; he must have been familiar with the treatises of Democritus and Anaxagoras on the use of perspective on the Greek stage; he must have abstracted the books on masks which Aristophanes of Byzantium had edited. The wealth of information contained in Jubas theater history can still be appraised, though indirectly and often despairingly, by an attempt to decipher the few puzzling pages which Pollux, relying on Juba, wrote on the physical aspects and masks of the Greek theater.

Next page