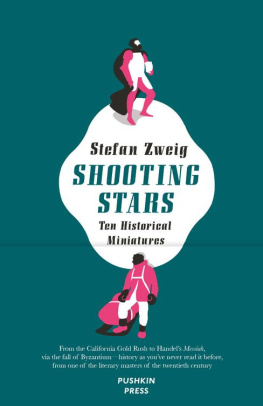

N O ARTIST is an artist through the entire twenty-four hours of his normal day; he succeeds in producing all that is essential, all that will last, only in a few, rare moments of inspiration. History itself, which we may admire as the greatest writer and actor of all time, is by no means always creative. Even in Gods mysterious workshop, as Goethe reverently calls historical knowledge, a great many indifferent and ordinary incidents happen. As everywhere in life and art, sublime moments that will never be forgotten are few and far between. As a chronicler, history generally does no more than arrange events link by link, indifferently and persistently, fact by fact in a gigantic chain reaching through the millennia, for all tension needs a time of preparation, every incident with any true significance has to develop. Millions of people in a nation are necessary for a single genius to arise, millions of tedious hours must pass before a truly historic shooting star of humanity appears in the sky.

But if artistic geniuses do arise, they will outlast their own time; if such a significant hour in the history of the world occurs, it will decide matters for decades and centuries yet to come. As the electricity of the entire atmosphere is discharged at the tip of a lightning conductor, an immeasurable wealth of events is then crammed together in a small span of time. What usually happens at a leisurely pace, in sequence and due order, is concentrated into a single moment that determines and establishes everything: a single Yes, a single No, a Too Soon or a Too Late makes that hour irrevocable for hundreds of generations while deciding the life of a single man or woman, of a nation, even the destiny of all humanity.

Such dramatically compressed and fateful hours, in which a decision outlasting time is made on a single day, in a single hour, often just in a minute, are rare in the life of an individual and rare in the course of history. In this book I am aiming to remember the hours of such shooting starsI call them that because they outshine the past as brilliantly and steadfastly as stars outshine the night. They come from very different periods of time and very different parts of the world. In none of them have I tried to give a new colour or to intensify the intellectual truth of inner or outer events by means of my own invention. For in those sublime moments when they emerge, fully formed, history needs no helping hand. Where the muse of history is truly a poet and a dramatist, no mortal writer may try to outdo her.

THE FIELD OF

WATERLOO

NAPOLEON

18 June 1815

D ESTINY MAKES its urgent way to the mighty and those who do violent deeds. It will be subservient for years on end to a single manCaesar, Alexander, Napoleonfor it loves those elemental characters that resemble destiny itself, an element that is so hard to comprehend.

Sometimes, however, very seldom at all times, and on a strange whim, it makes its way to some unimportant man. Sometimesand these are the most astonishing moments in international historyfor a split second the strings of fate are pulled by a man who is a complete nonentity. Such people are always more alarmed than gratified by the storm of responsibility that casts them into the heroic drama of the world. Only very rarely does such a man forcefully raise his opportunity aloft, and himself with it. For greatness gives itself to those of little importance only for a second, and if one of them misses his chance it is gone for ever.

Grouchy

The news is hurled like a cannonball crashing into the dancing, love affairs, intrigues and arguments of the Congress of Vienna: Napoleon, the lion in chains, has broken out of his cage on Elba, and other couriers come galloping up with more news. He has taken Lyons, he has chased the king away, the troops are going over to him with fanatical banners, he is in Paris, in the TuileriesLeipzig and twenty years of murderous warfare were all in vain. As if seized by a great claw, the ministers who only just now were still carping and quarrelling come together. British, Prussian, Austrian and Russian armies are raised in haste to defeat the usurper of power yet again, and this time finally. The legitimate Europe of emperors and kings was never more united than in this first hour of horror. Wellington moves towards France from the north, a Prussian army under Blcher is coming up beside him to render aid, Schwarzenberg is arming on the Rhine, and as a reserve the Russian regiments are marching slowly and heavily right through Germany.

Napoleon immediately assesses the deadly danger. He knows there is no time to wait for the pack to assemble. He must separate them and attack them separately, the Prussians, the British, the Austrians, before they become a European army and the downfall of his empire. He must hurry, because otherwise the malcontents in his own country will awaken, he must already be the victor before the republicans grow stronger and ally themselves with the royalists, before the double-tongued and incomprehensible Fouch, in league with Talleyrand, his opponent and mirror image, cuts his sinews from behind. He must march against his enemies with vigour, making use of the frenzied enthusiasm of the army. Every day that passes means loss, every hour means danger. In haste, then, he rattles the dice and casts them over Belgium, the bloodiest battlefield of Europe. On 15th June, at three in the morning, the leading troops of the greatand now the onlyarmy of Napoleon cross the border. On the 16th they clash with the Prussian army at Ligny and throw it back. This is the first blow struck by the escaped lion, terrible but not mortal. Stricken, although not annihilated, the Prussian army withdraws towards Brussels.

Napoleon now prepares to strike a second blow, this time against Wellington. He cannot stop to get his breath back, cannot allow himself a breathing space, for every day brings reinforcements to the enemy, and the country behind him, with the restless people of France bled dry, must be roused to enthusiasm by a draught of spirits, the fiery spirits of a victory bulletin. As early as the 17th he is marching with his whole army to the heights of Quatre-Bras, where Wellington, a cold adversary with nerves of steel, has taken up his position. Napoleons dispositions were never more cautious, his military orders were never clearer than on this day; he considers not only the attack but also his own danger if the stricken but not annihilated army of Blcher should be able to join Wellingtons. In order to prevent that, he splits off a part of his own army so that it can chase the Prussian army before it, step by step, and keep it from joining the British.

He gives command of this pursuing army to Marshal Grouchy, an average military officer, brave, upright, decent, reliable, a cavalry commander who has often proved his worth, but only a cavalry commander, no more. Not a hot-headed berserker of a cavalryman like Murat, not a strategist like Saint-Cyr and Berthier, not a hero like Ney. No warlike cuirass adorns his breast, no myth surrounds his figure, no visible quality gives him fame and a position in the heroic world of the Napoleonic legend; he is famous only for his bad luck and misfortune. He has fought in all the battles of the past twenty years, from Spain to Russia, from the Netherlands to Italy, he has slowly risen to the rank of Marshal, which is not undeserved but has been earned for no outstanding deed. The bullets of the Austrians, the sun of Egypt, the daggers of the Arabs, the frost of Russia have cleared his predecessors out of his wayDesaix at Marengo, Klber in Cairo, Lannes at Wagramthe way to the highest military rank. He has not taken it by storm; twenty years of war have left it open to him.