All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

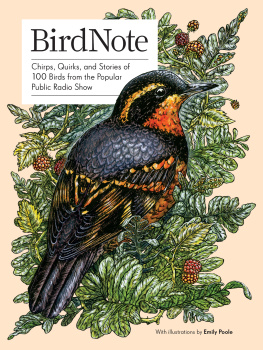

Foreword

ONE MORNING BACK IN 2004 , while working in my office overlooking Sapsucker Woods Pond, I received a phone call from Chris Peterson. At that time, Chris was executive director of Seattle Audubon, which I knew to be one of the most active and forward-thinking of the hundreds of Audubon chapters around the country. Chris had hatched a novel and ambitious idea, and was wondering if the Cornell Lab of Ornithology might be interested in playing a role. She was searching for a way to promote appreciation of birds and nature more widely than can be done through local nature centers and environmental classes. Her idea was to create a series of engaging stories about birds, to be broadcast around the country via two-minute slots. Knowing that the Cornell Lab was home to the Macaulay Librarythe worlds premier archive of acoustic recordings from natureshe wondered if wed be interested in providing the bird sounds. Without hesitation, my response to Chriss question was, Absolutely, yes! For one thing, I remembered that the Cornell Lab itself had created a similar program back in the early 1990s, called BirdWatch (written and narrated by Bob Kantor). That show was excellent but short lived, and since becoming director of the Lab in 1995, I had wondered how our great collection of bird sounds might get back on the air. Chriss idea was a brilliant solution. Secondly, I had long appreciated the power of radio for effective storytelling. Uncluttered by visual content, good audio stories accompanied by authentic sounds have captured our attention and unleashed our human imaginations since the very first days of radio. What better way than this to open the world of birds and nature to an increasingly urbanized general public?

Birds are natures most effective communicators to humans, and I think that this stems from their ability to stimulate both sides of our brain. Our aesthetic consciousness is drawn to their sheer beauty, their diversity, their ability to fly, and their remarkable, continent-scale migrations that mark the changing seasons. It is no wonder that artists from the earliest cave painters to the postmodernists have depicted birds in visual representations of every possible motif. So too have poets and songwriters since Homers era embraced the spiritual power of birds, as the voices of thrushes, larks, and nightingales open our hearts to nature. Birds also appeal to our intellectual side, because they teach us how nature works. Their accessibility and diversity make them so amenable to scientific study that most modern principles in ecology, evolution, animal behavior, and natural resource management are rooted in studies of birds. Moreover, as humans increasingly change the course of the natural world, birds provide sensitive barometers for measuring the health of our natural systems.

BirdNote stories brilliantly express all these contexts, from the purely aesthetic to the technical sciences of ornithology. Tightly constructed and informative stories, interwoven with evocative natural sounds, connect us to the richly varied world of birds. I can think of no better way for the world to experience first-hand the recordings of the Macaulay Library, so it is especially gratifying that BirdNote has become such a popular radio spot and podcast. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology is privileged indeed to be closely involved with this terrific piece of media history. Our ongoing contributions to BirdNote productions reflect the Labs deep commitment to outstanding partners who are dedicated to education and biodiversity conservation.

Finally, I encourage readers of this book to take note of the link provided with the list of shows, which connects to these stories on BirdNote.org. For those interested in exploring even further, all the hundreds of thousands of bird sounds archived at the Cornell Lab are available for free browsing and listening at MacaulayLibrary.org.

Long live BirdNote! There is no end to the astounding variety of stories yet to be told from the world of birds, and likewise no end exists to the variety of sounds of nature. So, at thirteen years and counting, I trust that this great radio program is just getting started.

John W. Fitzpatrick, director,

Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Introduction

BIRDS FASCINATE US in part because, like us, they are primarily visual and vocal animals. We hear their songs and see their colorful feathers. And above all, we envy their power of flight.

Humans have been involved with birds for many thousands of years. Our remote ancestors probably valued birds and their eggs primarily as nutritious foods. But symbolic involvement with birds also began in those earlier times, as shown in prehistoric cave paintings and the presence of feathers, especially those of eagles, crows, and ravens, in ancient graves. Even Neanderthals used bird feathers or claws as personal ornaments. The antiquity of peoples relationships with birds is also recorded in the myths of many cultures. Nearly all indigenous people of the North Pacific Coast of North America have raven and eagle stories. Although details of each cultures raven stories differ, certain attributes are nearly universal: the raven is always a magical creature able to take the form of a human, animal, or even inanimate object. It is a keeper of secrets, a trickster. Raven stories tell how worldly things came to be; they may also tell children how to behave.

Birds with unusual features have long attracted special interest. The Hoopoe, a bird with a long, thin beak and a strikingly crested head, turns up in the Quran, in a story about King Solomon and the queen of Sheba. Its striking appearance made the Hoopoe conspicuous. But the bird also attracted attention because it mysteriously disappeared in the autumn, only to appear again in spring. We can look to the Greeks to find some of the earliest recordings of bird migrationas far back as three thousand years ago in the writings of Homer and Aristotle. And the book of Job in the Bible, dating back to around the second millennium BC, mentions migrations of storks, swallows, and doves.