FOR MICHAEL

Published by Princeton Architectural Press

A MCEVOY GROUP COMPANY

202 Warren Street, Hudson, New York 12534

www.papress.com

2018 Princeton Architectural Press.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Sara Stemen Image research: Nolan Boomer

Designer: Benjamin English

Special thanks to: Janet Behning, Nicola Brower, Abby Bussel, Tom Cho, Barbara Darko, Jenny Florence, Jan Cigliano Hartman, Susan Hershberg, Lia Hunt, Valerie Kamen, Simone Kaplan-Senchak, Jennifer Lippert, Kristy Maier, Sara McKay, Eliana Miller, Wes Seeley, Rob Shaeffer, Paul Wagner, and Joseph Weston of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

NAMES : Volner, Ian, author.

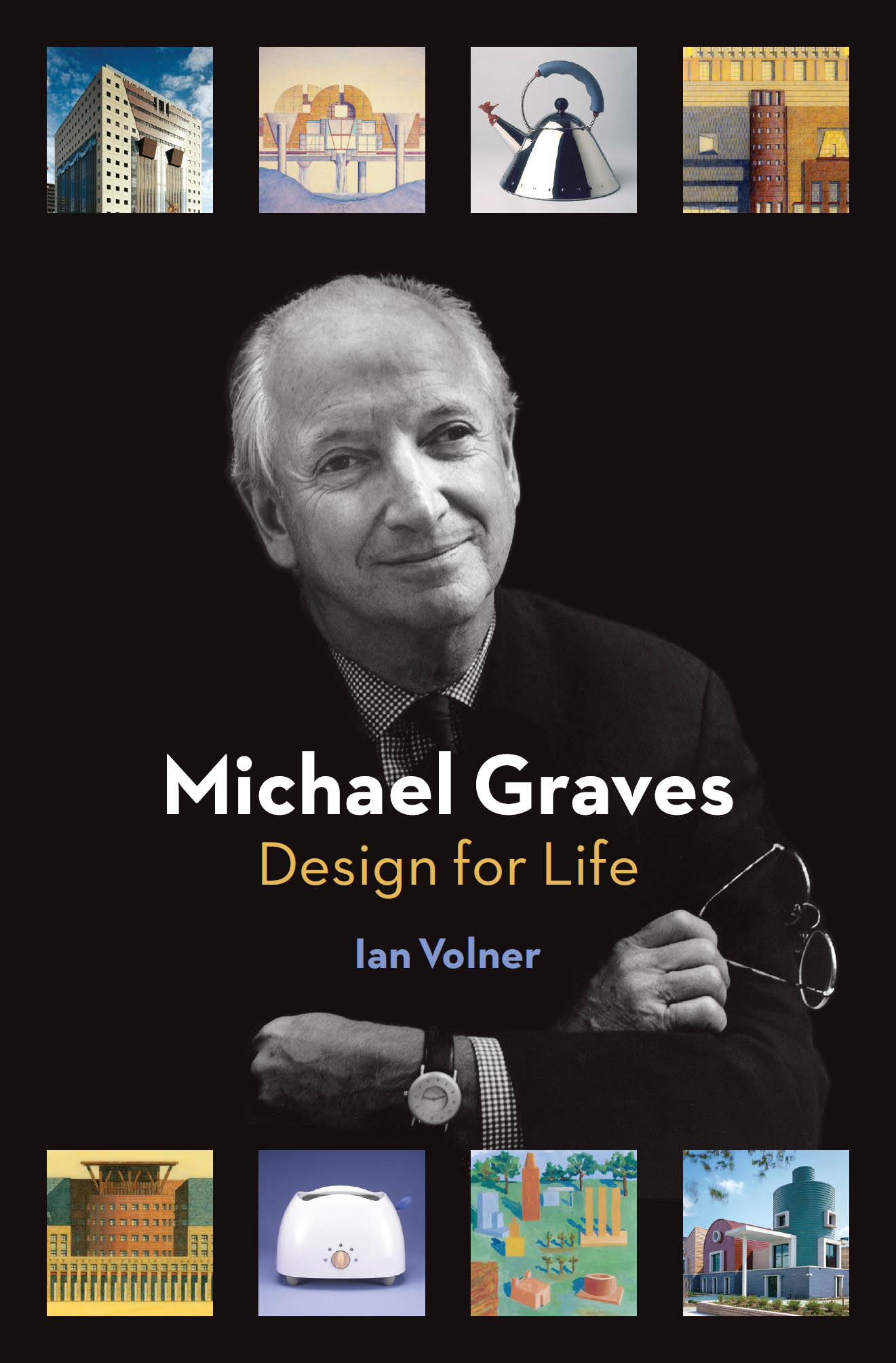

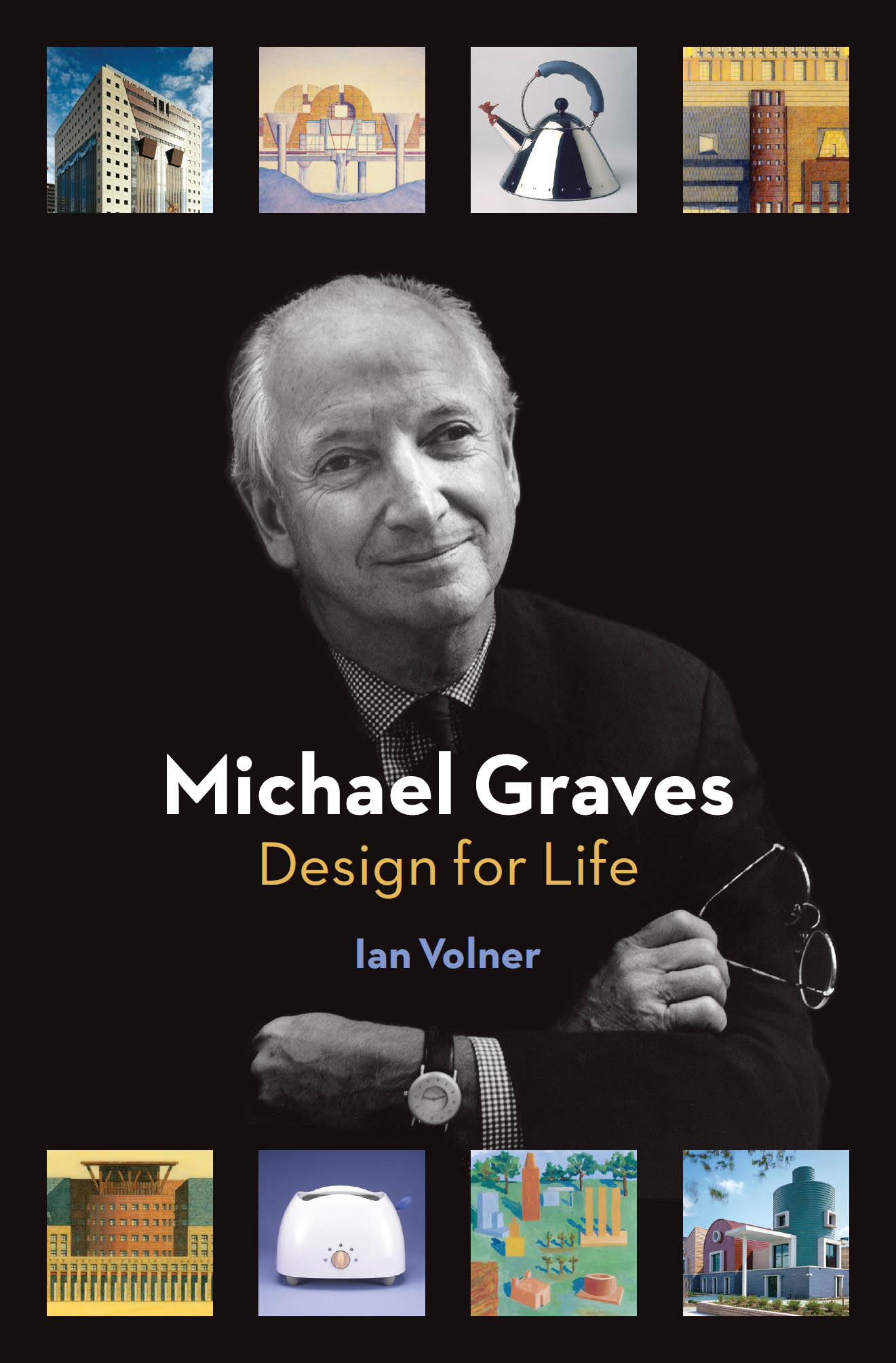

TITLE : Michael Graves : design for life / Ian Volner.

DESCRIPTION : First edition. | New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

IDENTIFIERS : LCCN 2016059450 | ISBN 9781616895631 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781616896850 (epub, mobi)

SUBJECTS : LCSH: Graves, Michael, 19342015Criticism and interpretation.

CLASSIFICATION : LCC NA737.G72 V65 2017 | DDC 720.92dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016059450

Contents

AND THE SONG

HAD FINISHED:

THIS WAS THE STORY.

John Ashbery, The Double Dream of Spring, 1970

I REQUEST, CAESAR,

BOTH OF YOU AND OF

THOSE WHO MAY

READ THE SAID BOOKS,

THAT IF ANYTHING

IS SET FORTH WITH

TOO LITTLE REGARD FOR

GRAMMATICAL RULE,

IT MAY BE PARDONED.

Vitruvius, De Architectura, I.1.17

Michael (in wire-frame glasses) and Peter Eisenman (in hat) with colleagues in the basement of the Princeton School of Architecture, circa 1964

Prologue

Trois rappels MM. les architectes

Le Corbusier

F ROM THE MOMENT he or she sits down to write, the biographers goose is pretty well cooked. There is no getting out from under the demands of the genrethe author must attempt to connect the life with the work. This is a dicey methodological proposition in any case, but especially in architecture, a creative endeavor with too many moving parts to be reduced, la Citizen Kane, to some long-lost childhood sled. And yet the present subject lends himself, more so than most architects, to the biographical treatment. Through his intense industry, as well as sometimes extraordinary happenstance, his work and his life entered into something like a cyclic loop, the one perpetually feeding back into the other. Whats more, examining the two together befits his particular architectural ethos, which took into its compass the personal and the universal, the monumental and the everyday. If ever a designers individual history afforded a handy guidebook for understanding both his own designs and the design of his times, it was this one, and the only thing to establish in advance is: Why should this designer, or his times, matter? And why now?

Heres one possible answer. Over and again during the last three and a half years, as I have researched, written, and edited this book, I have been put in mind of Bruno Latours landmark 1991 anthropological study, We Have Never Been Modern. Certainly its operating premisethat continuity is a more informative model of history than repeated disjuncturehas come to seem more and more pertinent. But it is Latours title that keeps coming back, albeit with a curious twist. In considering the life and afterlife of Michael Graves, his impact not just on the design profession but on the built environment as a whole, Ive begun to suspect that, in many of the ways that count, we have never stopped being Postmodern.

No doubt we had thought the moment long since come and gone. Postmodernist architecturePoMo as it is often called, with a slight sneerburst onto the American scene in the late 1970s amid a flourish of flattened columns and multihued facades.

At least Modernism had enjoyed a good three decades of unchallenged supremacy before the wrecking crews arrived. Postmodernism lasted scarcely half as long before being muscled aside by another ism. Only months before the Yonkers colonnade came down, New Yorks Museum of Modern Art debuted its Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition. Heralding an abstract and technically daring new approach from a roll call of soon-to-be-familiar names (among them Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid), the show was godfathered by Philip Johnson, Americas premier gadfly-tastemaker and until lately a major advocate of Postmodernist playfulness. The critics panned it, but Johnsons involvement sent a clear signal. For lovers of the nostalgic, the ironic, and the colorful, the lamps were going out all over architecture.

Theyve stayed that way ever sinceor so weve been told. The scholar Jean-Louis Cohen has characterized Postmodernism as a hesitation within the discourse, a moment when the profession apprehended with a start that much of the social promise of Modernism, its vision of a pristine utopia of glass and steel, had not been borne out. The reaction was less a radical break than a corrective reflex, almost like an immune response. Bubbling up through the academy in the early 1960s, the Postmodernist tendency began as a measured critical attack on the disruptions to the traditional urban fabric wrought by Modernist interventions; practice soon took up the cause, trying to mend that fabric by returning to its traditional constituents. Soon, Postmodernism was everywhere, manifesting in symptoms such as applied ornament, polychromatic surfaces, and familiar typological outlines.

These were already in evidence in what is generally recognized as the ur-Postmodernist project, Robert Venturis Vanna Venturi House, built for his mother in 1964. An idiosyncratic variant was popularized on the West Coast by Charles Moore, as in his collage-like Moore-Rogger-Hofflander condominium in Los Angeles of 1975. The architects dubbed the Chicago Seven (Stanley Tigerman foremost among them) would carry the banner for the movement in the Midwest, and Robert A. M. Stern and Jaquelin Robertson (and eventually Philip Johnson) would give it establishment cred in the East. Countless other firms would follow.

But, most importantly, there was Michael Graves. If Getty Square was PoMos Pruitt-Igoe, Gravess Portland Building of 1982 was perhaps its Seagram Building, the epochal moment of its architectural ascendancy. It thrust the Postmodernist movement to the forefront of the design world, and Graves himself to unprecedented international fame. During the 1980s he was indisputably the most celebrated, the most talked-about, American architect of his generation.

And thenthe fever broke. By the early 1990s other architects were vying with Graves for the covers of magazines, for major design awards, and for the idolatry of students at architecture schools everywhere. But what I have come to believe in the course of preparing this biography is this: when the hesitation of Postmodernism subsided and the architectural organism resumed its customary forward movement, its behavior was forever changed. For not only did Michael Graves himself not go away (in many ways his renown, and that of his office, only grew), but the problems and principles that concerned him most have never vanished. Quite the opposite: they remain a crucial part of design culture worldwide and are deeply embedded within practice as a whole, perhaps nowhere more so than in the very places where Gravess influence has been most effectively suppressed.

Next page