First published 1982 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

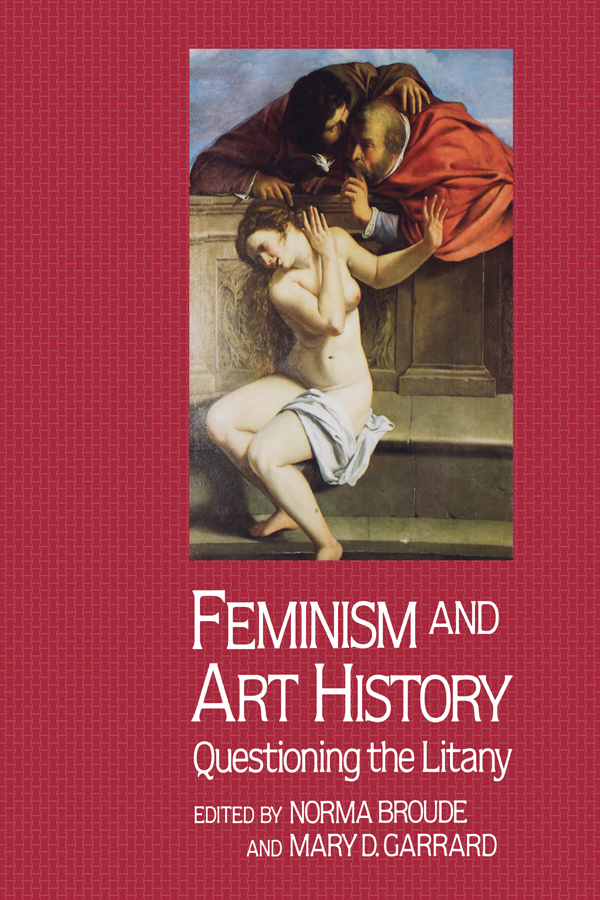

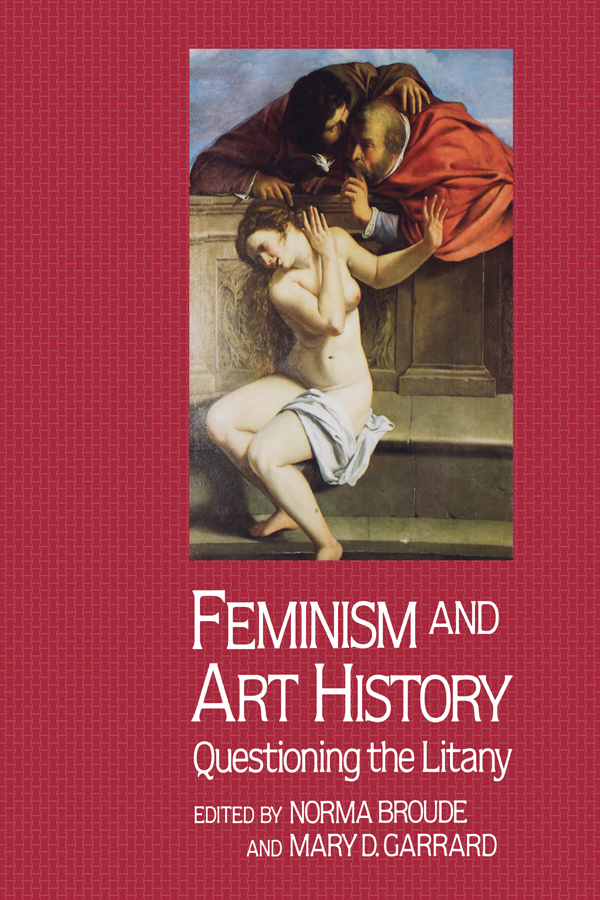

FEMINISM AND ART HISTORY. Copyright 1982 by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Book designed by C. Linda Dingier

Page layout by Abigail Sturges

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Main entry under title:

Feminism and art history.

(Icon editions)

Includes index.

1. Feminism and artAddresses, essays, lectures.

2. Feminism in artAddresses, essays, lectures.

I. Broude, Norma. II. Garrard, Mary D.

N72.F45F44 1982 701.03 81-48062.

AACR2

ISBN 13: 978-0-06-430117-6 (pbk)

Just over ten years ago the first feminist challenge was levied at the history of art with the publication in 1971 of Linda Nochlins essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, a consideration of the social and sexual prerequisites for the emergence of artistic genius. That was closely followed by the College Art Association (C.A.A.) session chaired by Nochlin in 1972 entitled Eroticism and the Image of Woman in Nine-teenth-Century Art, in which raw sexism in the creation and use of female imagery was so memorably exposed.

In response to these efforts, a session entitled Questioning the Litany: Feminist Views of Art History was held at the annual College Art Association Meeting in New York in 1978, under the sponsorship of the Womens Caucus for Art. Co-chaired by H. Diane Russell and Mary D. Garrard, the sessions purpose was to gather papers whose subjects were, in one way or another, reconsiderations from a feminist perspective of some of the standing assumptions of the discipline of art historypapers that held out, collectively, the possibility of the alteration of art history itself, its methodology and its theory, an aim to be distinguished from the additions to art history that were being provided in the same period by the rediscovery of numbers of forgotten women artists. In the following year, 1979, at the C.A.A. meeting in Washington, D.C., the Womens Caucus for Art sponsored a second Questioning the Litany session, chaired by Christine Mitchell Have-lock, in which the approach taken in the first session was continued and extended.

It was early in 1979 that the two of us decided to create and co-edit this book. The initial stimulus for this collection of essays was provided by the Questioning the Litany sessions themselves, the interest they generated, and the exhilarating sense of possibility the papers contributed to them had suggested. That stimulus is reflected in the books subtitle, and in the fact that four of the essays included herethose by Luomala, Alpers, Sherman, and one by Broudewere first delivered at a Questioning the Litany session.

In projecting the book, however, we decided to go beyond recording the particular programs of 1978 and 1979, and to collect papers and articles written over the past decadeand even earlierthat would best represent the full scope of the challenge that feminism has placed before art history. Thus, two of the seventeen essays included were first published in the pioneering Feminist Art Journal the one by Mainardi on quilts in 1973, and the one by Hofrichter on Judith Leyster in 1975. Another four of the essays were originally published in The Art Bulletin, the scholarly journal of our disciplines professional organization, the College Art Association of America. The earliest of them, Kahrs Delilah, was presented at a C.A.A. meeting in 1970 and published in The Art Bulletin in 1972; it was followed by Duncans Happy Mothers, read in 1972 and published in 1973; Broudes Degas, read in 1975 and published in 1977; and Nochlins Lost and Found published in 1978.

In making our selections for this volume, some choices were obvious ones while others came harder, since feminist revisionist activity has occurred with greater vigor in some historical periods than in others. Much to our regret, space limitations, and the desire to have a reasonably balanced coverage of major historical periods, prevented our including some excellent work that surely belongs in a collection of this kind.

By bringing together in one volume both new essays and many that have been published elsewhere, we hope to provide a context in which the individual importance of each essay may be better understood in relation to the larger issue and task before us. As a compendium of important recent ideas on the subject, the book will, we hope, be of use to scholars, students, and general readers unfamiliar with the effect of feminist thinking on art history. Beyond that, however, we would like to see this collection stimulate more work in the same vein. Each of the essays in the book is a ground-breaking effort, both for the historical period it addresses and for the specific ways in which its subject is reexamined. Many more artists, periods, and cultures deserve new critical scrutiny; the possibilities are infinite.

In planning and preparing this book for publication, we are fortunate to have had encouragement and assistance from many quarters. First, we must acknowledge the invaluable support that came from the Womens Caucus for Art in providing a continuing forum for these ideas. In particular, we thank Judith K. Brodsky, who was president of the Caucus at the time of the first Questioning the Litany session, and who has been especially encouraging from that time to now. We would also like to thank innumerable other friends in the Caucus and in the Coalition of Womens Art Organizations, whose enthusiasm for this project has helped to sustain us.

We are grateful for support from our own institution, The American University, and from the College of Arts and Sciences, which awarded us a Mellon Faculty Development Grant to facilitate this project. Among the friends and colleagues at the University who encouraged our project, we would particularly like to mention Ann Ferren, Kay Mussell, and Roberta Rubenstein. We have greatly appreciated the confidence and backing of the Art Department, and we are especially thankful for the continuous interest and enthusiasm that has come from our students, our sharpest and most valued critics.

We would like to express special appreciation to the contributors to this volume. They have all been marvelous to work with. The book has benefited in a variety of ways from their suggestions and advice, and our own job as editors has been made much easier by their cheerful cooperation and patience.

We would like to thank Madlyn Millner Kahr and Cass Canfield, Jr., for believing in this book.

And, finally, we would like to express our gratitude to each other, for the qualities of intellectual stimulus, psychological complement, creative disagreement, and mutual appreciation that are the essence of a productive partnership, and of a whole that is more than the sum of its parts.

Notes

. Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, Art News, 69, no. 9, January 1971, pp. 22-39, 67-71. The papers read at Nochlins C.A.A. session were published in Woman as Sex Object, Studies in Erotic Art, 1730-1970, ed. by Thomas B. Hess and Linda Nochlin, Art News Annual 38, Newsweek, Inc., New York, 1973. They include Nochlins Eroticism and Female Imagery in Nineteenth-Century Art, pp. 8-15.