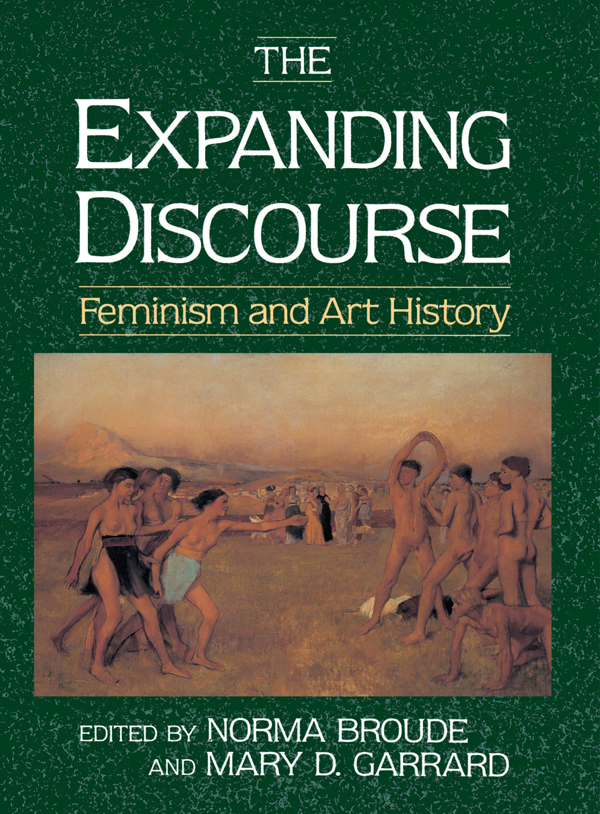

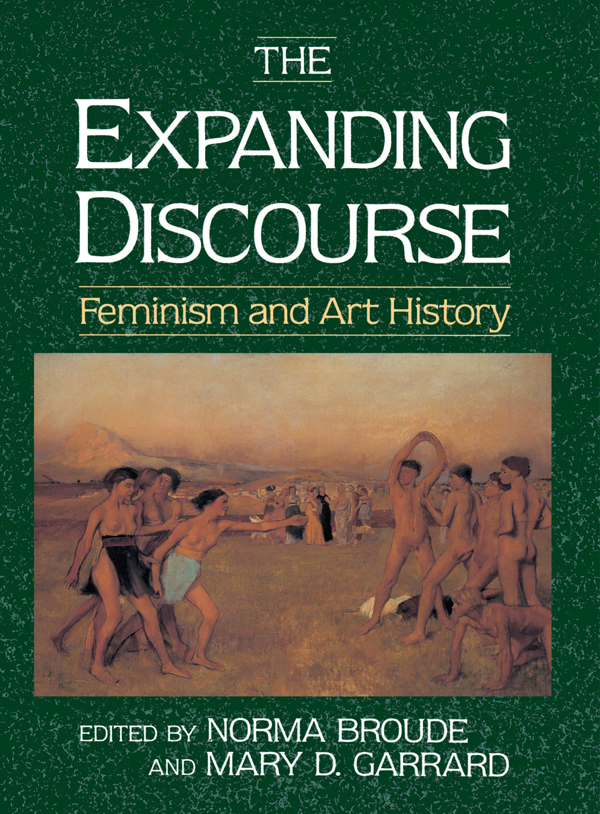

THE EXPANDING DISCOURSE: FEMINISM AND ART HISTORY.

First published 1992 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1992 by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Designed by Abigail Sturges

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Expanding discourse feminism and art history / edited by Norma

Broude and Mary D. Garrard.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-06-430391-8 (cloth) / ISBN 0-06-430207-5 (pbk.)

1. Feminism and art.I. Broude, Norma.II. Garrard, Mary D.

N72.F45E961992

704.042dc20

91-58341

ISBN 13: 978-0-06-430207-4 (pbk)

The twenty-nine essays assembled in this volume represent what is to our minds somethough certainly not allof the best feminist art-historical writing of the last decade. In gathering materials for our first volume in 1981, we found ourselves literally working to define a new genre of art-historical investigation, one that was distinguished more by an attitude than by a methodology, and which had not yet been given a name or a clear identity. Our selections came from a wide array of sources: some were conference papers; a few came from the ground-breaking, now defunct Feminist Art Journal; others were unpublished. A surprising number of pieces came from published books and from mainstream journals such as The Art Bulletin , and many of these had not been written from a self-consciously feminist point of view. We pulled these disparate contributionson topics and periods ranging from prehistory to the twentieth centurytogether into a new whole, to demonstrate the possibility of a continuous feminist perspective on art history in every cultural period.

A decade later, our task was entirely different. We were confronted by a rich harvest of scholarship in art history, nourished by new theoretical and critical perspectives and by the new interdisciplinary fields of womens studies and gender studies. The problem now was what to select from that wealth of publications that might best represent its abundance, diversity, and main conceptual threads. One of our earliest decisions was to limit the scope of this volume to the period from the Renaissance to the present, since much of the work done by feminist art historians in the last decade has focused on this time span. We felt that the connections among the essays, as well as the usefulness of the book, would be strengthened by this chronological focus. And considering the plethora of examples of feminist art-historical scholarship in articles and essays, we also decided not to include any excerpts from books, nor examples of feminist art criticism. By now, these are exemplary categories in their own right. The former is represented, for example, by such publications as Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (Thames and Hudson, 1985 and 1991); Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign, 190714 (University of Chicago Press, 1988); Gloria Feman Orenstein, The Reflowering of the Goddess (Pergamon Press, 1990), and H. Diane Russell, Eva/Ave: Women in Renaissance and Baroque Prints (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1990, and The Feminist Press, 1991). The latter category is represented, for example, by Arlene Raven, Cassandra L. Langer, and Joanna Frueh, eds., Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology (UMI Research Press, 1988, and HarperCollins, 1991).

Our selection has been guided as well by a distinction that is elusive but important. All of the essays included here take, in our view, a feminist as opposed to a gender-conscious approach to art and art history. Gender-focused analysis purports to aim for an even-handed exploration of sexual difference, and therefore proceeds from what appears to be a value-neutral position. For example, a recent trend in gender studies has been the investigation of gendered subjectivity as the underpinning for art movements that have been masculinist preserves, such as Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. Such gender-conscious analyses may show us, by implication, how and why it was that women had no access to the Abstract Expressionist and Minimalist myths, but this is not their stated mission or goal. Their focus remains male centered, like the canonical art history that enshrined these styles in the first place, and whose values they now self-consciously name but still often tacitly accept and perpetuate. In looking at male subjectivity in isolation, such analyses leave untouched the cultural assumption that artistic agency is a male prerogative, thus reifying both the values and the power mechanisms of the styles in question. In a society still largely patriarchal and still gender imbalanced, such purported neutrality/ it seems to us, is premature and effectively pro-masculinist.

Feminist scholarship, on the other hand, proceeds from the recognition that our histories and the values that shape them have been falsified, because of the asymmetrical power positions of the sexes. Seeing the writing of history as a process of continual correction and expansion, feminist scholars find their mission in the need to set things right. Their subject is not neutral material, but a nest of live distortions here, a basket of telling omissions there. Feminist scholars share a commitment to change history, by creating a fuller and more accurate account of the part played both by real women and by thematized and constructed Woman in its making. It is important, we believe, to sustain this feminist project as long as it serves a corrective need.

We extend our gratitude to the contributors to this book, first for their creative and ground-breaking work, but also for their enthusiastic support of this project and their cooperation in bringing this book to fruition. We are especially grateful for the trust and professional respect implied in the ready agreement, on the part of every contributor, to be included in a book whose contours were as yet unknown.

We are most deeply indebted to Cass Canfield, Jr., our editor at HarperCollins (and before its name change, Harper & Row). It is to Casss extraordinary vision that both Feminism and Art History and The Expanding Discourse owe their existence, in the first case when his intuition proved more reliable than that of a substantial number of naysaying editors at other houses, and in the second case when he persuaded us of the need for a sequel volume. We have once again enjoyed the support and assistance of the admirable professional staff at Harper, especially Bronwen Crothers, Bitite Vinklers, and our designers, C. Linda Dingier and Abigail Sturges.

And, once again, we thank one another, for inspiration and criticism, patience and tolerance, creative differences and constructive disagreements, and for the joys and pleasures of a fruitful collaboration.

MARILYNN LINCOLN BOARD is Assistant Professor of Art History at the State University of New York, Geneseo. Her other publications include articles on G. F Watts, Alice Neel, and Nancy Spero. Two books in progress explore the iconography of Spero and Watts.