Text: after Edmond de Goncourt

Translated from the French by Michael & Lenita Locey

Layout:

Baseline Co Ltd.

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

Nam Minh Long, 4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights of adaptation and reproduction reserved for all countries.

Except as stated otherwise, the copyright to works reproduced belongs to the photographers who created them. In spite of our best efforts, we have been unable to establish the right of authorship in certain cases. Any objections or claims should be brought to the attention of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-703-2

Edmond de Goncourt

UTAMARO

Contents

Hanagi of thegiya [kamuro:] Yoshino,

Tatsuta (giya uchi Hanagi), 1793-1794.

ban, nishiki-e, 36.4 x 24.7 cm.

Muse national des Arts asiatiques Guimet, Paris.

FOREWORD

In his Life of Utamaro, Edmond de Goncourt, in exquisite language and with analytical skill, interpreted the meaning of the form of Japanese art which found its chief expression in the use of the wooden block for colour printing. To glance appreciatively at the work of both artist and author is the motive of this present sketch. The , the title of which forms a pretty play upon words, maro being the Japanese for vessel, the seal of supremacy is set upon the artist. He was essentially the painter of women, and though de Goncourt sets forth his astonishing versatility, he yet entitles his work Utamaro, le Peintre des Maisonsvertes.

Dora Amsden

Snow, Moon and Flowers from thegiyaTea House

(Setsugekka Hanagi), Kansei period (1789-1801).

ban, nishiki-e, 36.2 x 24.9 cm.

Muse national des Arts asiatiques Guimet, Paris.

Woman Making up her Lips (Kuchibiru), c. 1795-1796.

ban, nishiki-e, 36.9 x 25.4 cm. Private Collection, Japan.

I. THE ART OF UTAMARO

To leaf through albums of Japanese prints is truly to experience a new awakening, during which one is struck in particular by the splendour of Utamaro. His sumptuous plates seize the imagination through his love of women, whom he wraps so voluptuously in grand Japanese fabrics, in folds, contours, cascades and colours so finely chosen that the heart grows faint looking at them, imagining what exquisite thrills they represented for the artist. For womens clothing reveals a nations concept of love, and this love itself is but a form of lofty thought crystallised around a source of joy. Utamaro, the painter of Japanese love, would moreover die from this love; for one must not forget that love for the Japanese is above all erotic. The : the love of beauty in an artist is not real unless he has the sensuality for it. Love and sex are at the foundation of aesthetic feelings and become the best way to exteriorise art which, in truth, never renders life better than by schematisation, by stylisation.

Among the artists of the Japanese movement of the floating world (Ukiyo), Utamaro is one of the best known in Europe; he has remained the painter of the green houses, as he was called by Edmond de Goncourt. We associate him at once with the colour prints () of his great willowy black-haired courtesans dressed in precious fabrics, a virtuoso performance by the printmaker.

In addition to romantic scenes set in nature, he dealt with themes such as famous lovers together, portraits of courtesans or erotic visions of the . But it is Utamaros portrayals of women which are the most striking by their sensual beauty, at once lively and charming, so far removed from realism, and imbued with a highly-refined psychological sense. He offered a new ideal of femininity; thin, aloof, and with reserved manners. He has been criticised for having popularised the fashion of the long silhouette in women and giving these figures unrealistic proportions. He was, to be sure, one of the prominent representatives of this style, but his portraits of women, with their distorted proportions, remain works of an art which is marvellous and eminently Japanese. In truth, the Japanese value nobility in great beauty more highly than observation and cleverness. Subtly, the evocative approach brings beauty to full flower, offers its thousand facets to the eye, astonishes by a complexity of attitudes which are more apparent than real and takes absurd liberties with the truth, liberties which are nonetheless full of meaning.

Little is known of the life of Utamaro. Ichitar Kitagawa, his original name, is said to have been born in Edo around the middle of the eighteenth century, probably in 1753, certainly in Kawagoe in the province of Musashi. It is a time-honoured tradition of Japanese artists to abandon their family name and take artistic pseudonyms. The painter first took the familiar name of Ysuke, then as a studio apprentice the name Murasaki, and finally, as a painter promoted out of the atelier and working in his own right, the name of Utamaro.

Utamaro came to Edo at a young age. After a few years of wandering, he went to live at the home of Tsutaya Jzabur, a famous publisher of illustrated books of the time, whose mark representing an ivy leaf surmounted by the peak of Fujiyama, is visible on the most perfect of Utamaros printings. He lived a stones throw from the great gates leading to the . When Tsutaya Jzabur moved and set up shop in the centre of the city, Utamaro followed and stayed with him until the publishers death in 1797. Thereafter Utamaro lived successively on Kyemon-ch St, Bakuro-ch St, then established himself, in the years preceding his death, near the Benkei Bridge.

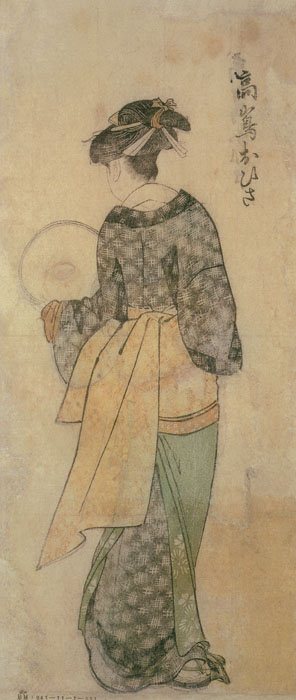

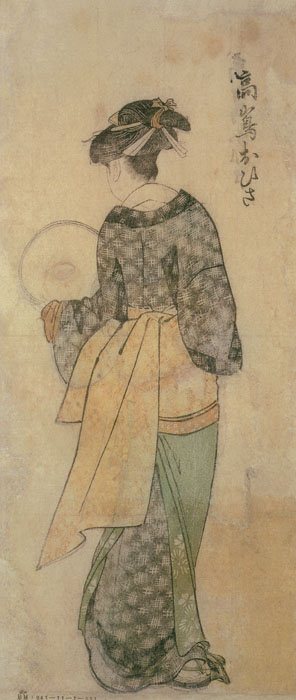

Naniwaya Okita, 1792-1793. Hosban,

nishiki-e (double-sided (back view shown)),

33.2 x 15.2 cm. Unknown Collection.

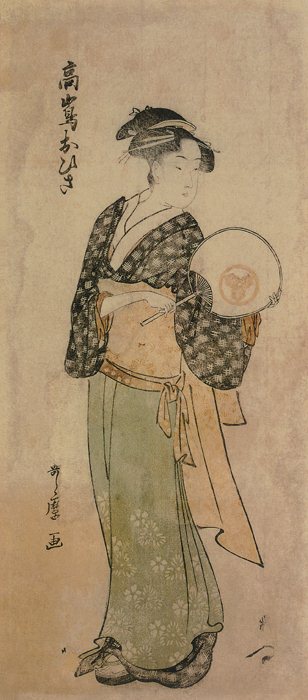

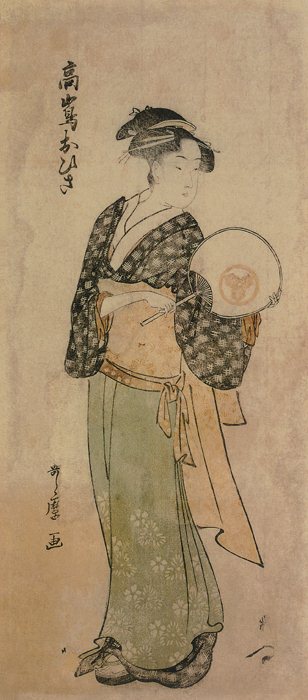

Naniwaya Okita, 1792-1793. Hosban,

nishiki-e (double-sided (front view shown)),

33.2 x 15.2 cm. Unknown Collection.

He first studied painting at the school of Kan. Then, while still quite young, he became the pupil of Toriyama Sekien. Sekien taught him the art of printing and of were lavishly illustrated by Utamaro. His collaboration with Tsutaya Jzabur, whose principal artist he soon became, marked the beginning of Utamaros fame. Around 1791, he left book illustration to concentrate entirely on womens portraits. He chose his models in the pleasure districts of Edo, where he is reputed to have had many adventures with his muses. By day, he devoted himself to his art and by night, he succumbed to the fatal charm of this brilliant underworld, until the time when, seduced by the tiny steps and hand gestures, his art undermined by excess, he lost his life, his name and his reputation.

Next page