PLEASURE BOUND

VICTORIAN SEX REBELS AND THE NEW EROTICISM

Deborah Lutz

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY  New York London

New York London

Copyright 2011 by Deborah Lutz

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lutz, Deborah.

Pleasure bound: Victorian sex rebels and the new eroticism / Deborah Lutz.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-08067-4

1. Sex customsGreat BritainHistory19th century. 2. ArtistsGreat BritainSexual behavior. 3. Great Britain Social life and customs19th century. I. Title.

HQ18.G7L88 2011

306.77094209034dc22

2010027029

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For P.J.L.

Contents

Dante Gabriel Rossettis Beata Beatrix , a painting of Lizzie Siddal, finished after her death. Rossetti captures the moment Dantes Beatrice dies.

Edward Burne-Joness King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid , with the maids eyes full of an inward-directed melancholy.

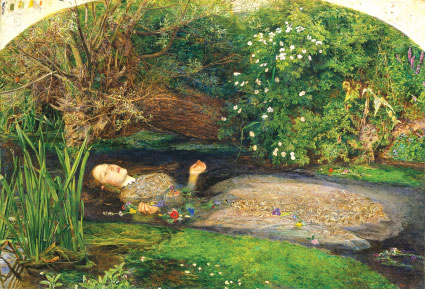

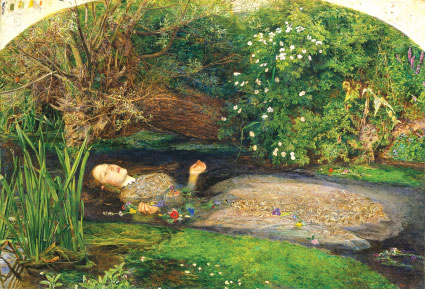

John Everett Millaiss Ophelia , modeled by Lizzie Siddal. He pictures Ophelias death as orgasmic.

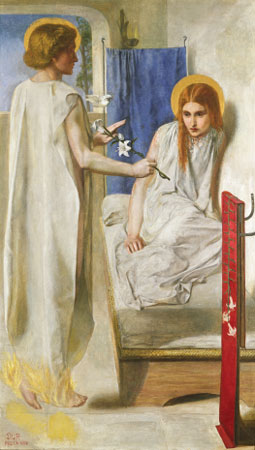

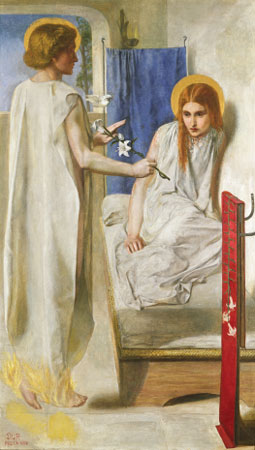

Dante Gabriel Rossettis Ecce Ancilla Domini! , an annunciation scene modeled by a young Christina Rossetti as the virgin Mary.

Dante Gabriel Rossettis Astarte Syriaca , modeled by Jane Morris, who was given an androgynous body.

Simeon Solomons The Mystery of Faith , with a beautiful man carrying a reliquary containing the host.

Dante Gabriel Rossettis The Blue Bower , modeled by Fanny Cornforth, who appears to be sitting inside a blue-and-white Chinese porcelain pot.

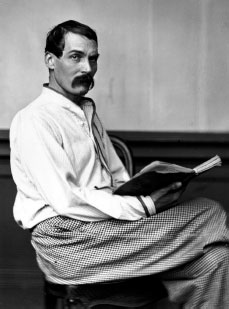

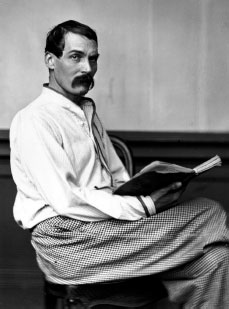

Richard Francis Burton in 1864, looking worthy of Swinburnes crush.

Oscar Wilde, around 1894, when he wrote The Importance of Being Earnest and was busy feasting with panthers.

Acknowledgments

I WANT TO BEGIN by expressing my gratitude to my sister, Pamela Lutz, whose tenderness provides a backdrop to all my best work. I owe Maggie Nelson a great debt for being a brilliant and enthusiastic reader of this book and for helping me to understand more about pleasure. Benjamin Friedman has my gratitude for his unwavering attention to the minute and for his special ability to locate clusters. And for his willingness to share rooms, cities, and architecture with me. I am grateful to Kristofer Widholm for those countless hours we spent in that sunny kitchen, sharing the same workspace. Thanks to my mother for her pride in me. Wayne Koestenbaum taught me about pornography and the erotics of collaboration. Jean Mills shows me how to push through and gives me her fire in the woods. Thanks to Elaine Freedgood for her unflagging encouragement and for telling me about materiality. Melissa Dunn demonstrated the value of stepping outside of academia. Talia Schaffer I thank for her many words of support and for telling me about womens crafts and their collaborative sharing. Conversations about sexuality with Duc Dau and Will Fisher provided me with ideas, early and late. The kindness, wit, and enthusiasm of my colleagues at Long Island University helped me clear space to write; James Bednarz, Rachel Szekely, Tom Fahy, Katherine Hill-Miller, and John Lutz remain especially in my mind. I am grateful to my agent, Renee Zuckerbrot, for her astute professionalism and her cheerful persistence. At W. W. Norton, Amy Cherry enriched this book with her wise and sensitive editing. And thanks to Deborah Rubin, who persuades me to find pleasure, even in what seems most impossible.

I wish to thank Long Island University for two grants that made the pictures possible.

Introduction

D ID I TELL you that I saw Powell when he was here and that he carried off a little picture of mine that I painted in Rome? I have had it photographed and I write a line under it from Hermaphroditus Love turned himself and would not enter in, penned the painter Simeon Solomon to his intimate friend Algernon Charles Swinburne in the first cool days of autumn in 1869. This little painting depicted Swinburnes poem about the erotic attractions of a fellow who is neither a woman nor a man. Swinburne and Solomon were groping their way toward a new view of the sexual body, at a time when the artists and writers of their set were testing, in their work and lives, the boundaries of sexual propriety. If one was neither female nor male, then might all gender rules get thrown out the window? A month earlier, in a momentous break from tradition, Girton, the first college for women at Cambridge, was established. Respectable gentlemen prowled the night streets of London for young grenadiers to bend them over in a public toilet.

Solomon and Swinburne joined, in 1860s London, two loosely overlapping groups of men who were more than usually involved in questions of erotic freedom and expression. Not only did many of them navigate the fringes of sexual deviance with their bodiesfrequenting flagellation brothels, sleeping with a best friends wife, cruising for male-male anonymous sexbut they carried the pleasures of the body into their work. Rather astonishingly, out of these two clansthe Cannibal Club and the Aesthetessprang most of the sexually themed writing and painting (including out-and-out pornography) of the latter half of the nineteenth century. Much of what they dipped their hands into feels strangely modern to us today. Dante Gabriel Rossetti painted sickness and death with sensual longing. Cropping up are memoirs penned solely to recount sexual exploits, failures, and torment. Richard Burton brought out how-to manuals on sex positions, like a Victorian Dr. Ruth. Littered throughout their work are glimmerings of what feels like the future: the femme fatale, S-M implements, Christian symbolism turned homoerotic.

Yet all the while these fellows remained deeply dyed in Victorian thinking and beingsteeped, even in their acts of rebellion, in their contemporary scene. Forming the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, the young artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt made a gesture of defiance against the establishments adoration of painters before Raphaelthe master of three-dimensional, Renaissance perspective. Rossetti and his brothers (which also included his sister Christina) called themselves pre-Raphael because they imitated the flat, one-dimensional perspective of the quattrocento (fifteenth-century Italy) artists, including painters like Fra Angelico whose style seemed splendidly primitive alongside the floridity of Raphael. The Brotherhood had largely broken up by 1853, but in the early 1860s another set, this one more sensually attuned and politically radical, began to pool around Rossetti.

![Advait - Mudras for Sex: 25 Simple Hand Gestures for Extreme Erotic Pleasure & Sexual Vitality: [ Kamasutra of Simple Hand Gestures ]](/uploads/posts/book/81294/thumbs/advait-mudras-for-sex-25-simple-hand-gestures.jpg)

New York London

New York London