While still a teenager, during the Second World War, my mother-in-law began drawing portraits of hospitalized soldiers. I never discussed this with her. By the time I began to contemplate a book set in Detroit during the War, she had been dead some twenty years. But it was a heartening moment when I realized that this vanished woman was offering me, from beyond the grave, with characteristic generosity, another gift: the premise for a novel.

My heroine, Bianca Paradiso, has few connectionsof appearance, of character, of familywith my mother-in-law, who was born Lormina Paradise and who composed her soldier-portraits in various places, including New York City. But I retained, as an act of fealty, her surnamegoing it one better by restoring its original spelling. And I proceeded over the years of the books writing with a strong sense that it must serve as a tributeto my mother-in-law, and to my parents, whose Midwest I would seek to capture, and not least to Detroit itself, my beleaguered and beloved hometown, in all its clanking, gorgeous heyday.

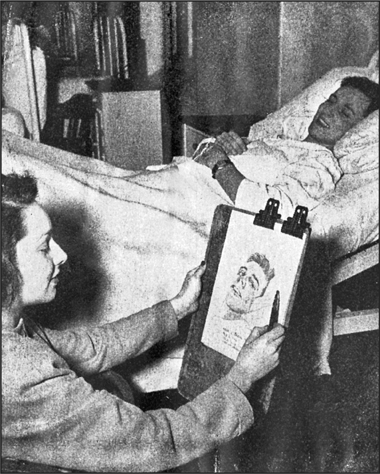

My mother-in-law gave the portraits to the soldiers themselves. What Im left with are, literally, copies of copies of copies. A few of these have been scattered throughout these pages, as well as a solitary photograph: artist, bed-ridden soldier, and the portrait that binds them. Its a small image that seemed to summon me to write a large and grateful book.

PART ONE

The War Comes Home

CHAPTER I

When the streetcar halts at Woodward and Mack, the young soldier who climbs aboard with some difficultyhe looks new to his crutchesis surpassingly handsome. Everybody notices him. His hair, long for a soldiers, is shiny black. His eyes are arrestingly blue. That gaze of his is slightly unnerving and suggests a sizable temper, maybe. Or maybe not, for the crooked grin he releases at seeing himself securely aboard is boyish and winsome. Everybody in this dusty car feels heartened by him. A nation capable of producing soldiers as stirring as this young soldierhow could it possibly lose the War?

Although she doesnt allow herself to stare openly, nobody is more observant of the handsome wounded young soldier than someone called Bea, whose true name is Bianca: Bianca Paradiso. A tall girl wearing a red hat, she stands in the middle of the car. The War has been unfolding for what feels like ages and those tranquil days before the soldiers overran the streets seem to belong to her childhood. The olive drab and navy blue of the boys uniforms have reconstituted the palette of the city. Bea is an art student. She examines minutely the citys streets and streetcars, parks and store-window displays and billboards, and of course its automobiles. Her teacher last quarter, Professor Evanman, spoke of automobiles as the citys blood vesselsthis is, after all, the Motor Cityand he urged his students to view Detroit as a living creature. The advice struck powerfully: the city as a living creature. Bea is eighteen.

She cultivates these days an enhanced receptivity to color, including the heavy black of this soldiers hair, and the hovering, weightless, gas-fire blue of his eyes, to say nothing of the emphatic fresh white of the plaster bandage encasing his left leg. Bea is heading home from a two-hour class in still-life painting. Her professor this term is Professor Manhardt, who would never counsel his students to contemplate anything automotive. Professor Manhardt is a purist. He, too, offers inspiring advice. An artist never stops mixing paint Thats one of Professor Manhardts maxims, and while heading home from class Bea typically entertains a drifting armada of colors without objectsbig floating swatches and swirls of pigment.

Yes, servicemens uniforms have colored the city for a long time, but its only recently, in this sodden late spring of 1943, that youve begun to see many of the wounded. Theres a special light attending them, like El Grecos figures. Each glimpse of a wounded soldier forces you into a fearful medical appraisal. How bad is he hurt? Thats always the first question in everybodys mind. And Please, God, not too badly Thats the follow-up prayer. Please, God. Fortunately, nobody Bea personally knows has been wounded or killed, so far at least, although a high school classmate, Bradley Hake, has long been missing in action in the Philippines.

Well, this one, the very good-looking boy on the Woodward Avenue streetcar, isnt hurt too badly. Though his leg is bandaged all the way above his knee, and though he grimaced on the car step, he exudes a brimming youthful well-being once aboard. Its so good to be home, his grin declares. Good to be alive in a month in which, as the newspapers daily report, American boys by the hundreds are dying overseas. Yes, truly it is wonderful to be back in Detroit, on this last Friday in May, the twenty-eighth of May, after a record-breaking stretch of rainy days, riding a streetcar up Woodward Avenue, the citys central thoroughfare, with a mixed crowd of people who aremen and women, white and coloredheading home for supper.

Its approaching five oclock and the streetcar is full, with recent arrivals like Bea left standing. Streetcars are always full, ever since the War started. Of course theres not a chance in the world the soldier will be left standing. Its only a matter of whos to have the honor of first catching his eye and offering up a seat.

This privilege falls to a badly shaved, grizzled little man wearing a patched jacket and a tan corduroy cap. His hands, although scrubbed, are still grimed from a day at the factory. Bea observes everything. As he rises from his seat he instinctively doffs his tan cap, revealing a threadbare scalp on which a nasty-looking boilhis own modest woundgleams painfully. If the young black-haired soldier had been his own flesh and blood, the grizzled little man couldnt regard him with deeper paternal satisfaction. The man with the boil has been granted an opportunity both honorable and precious: the chance for a small but conspicuous display of patriotism.