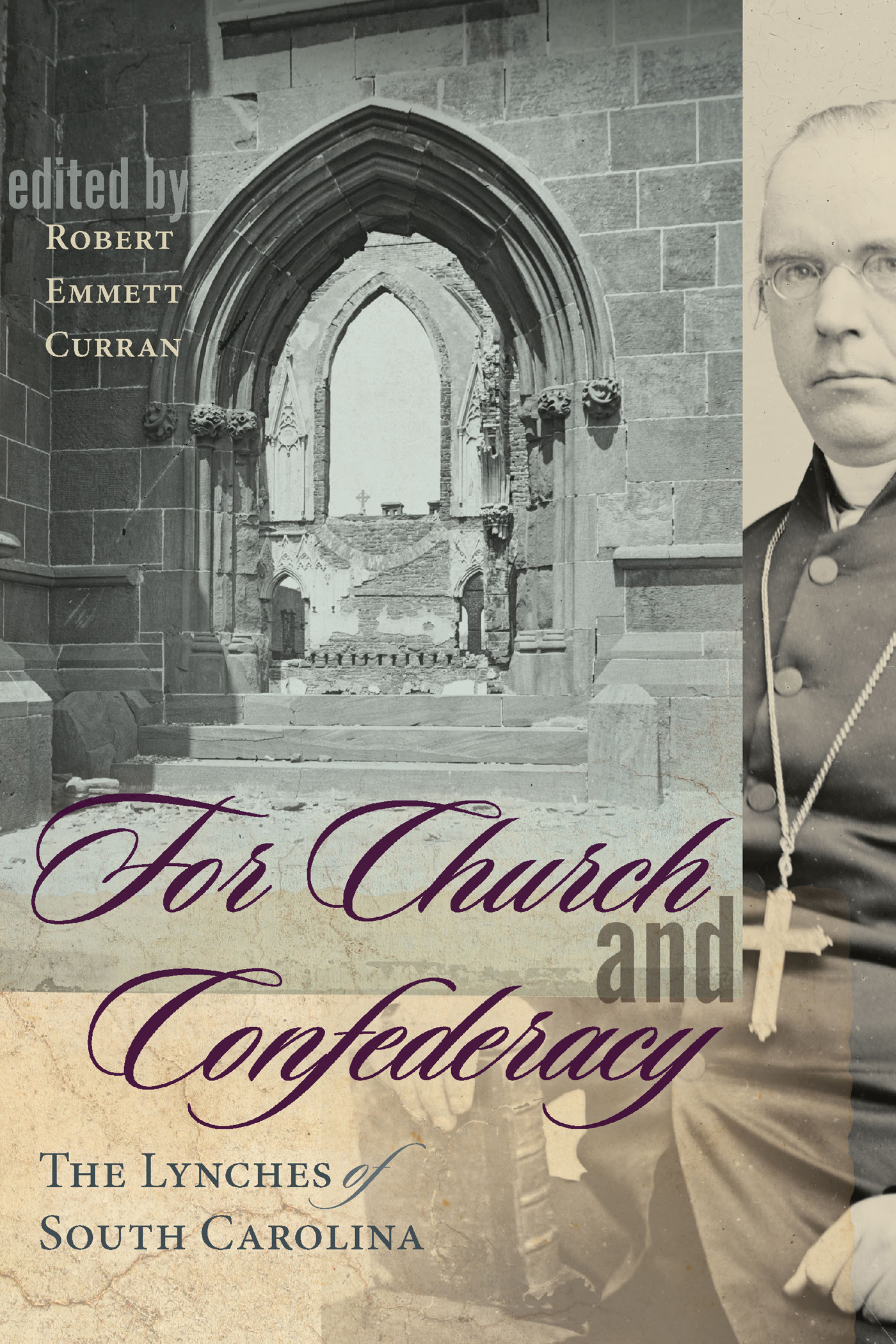

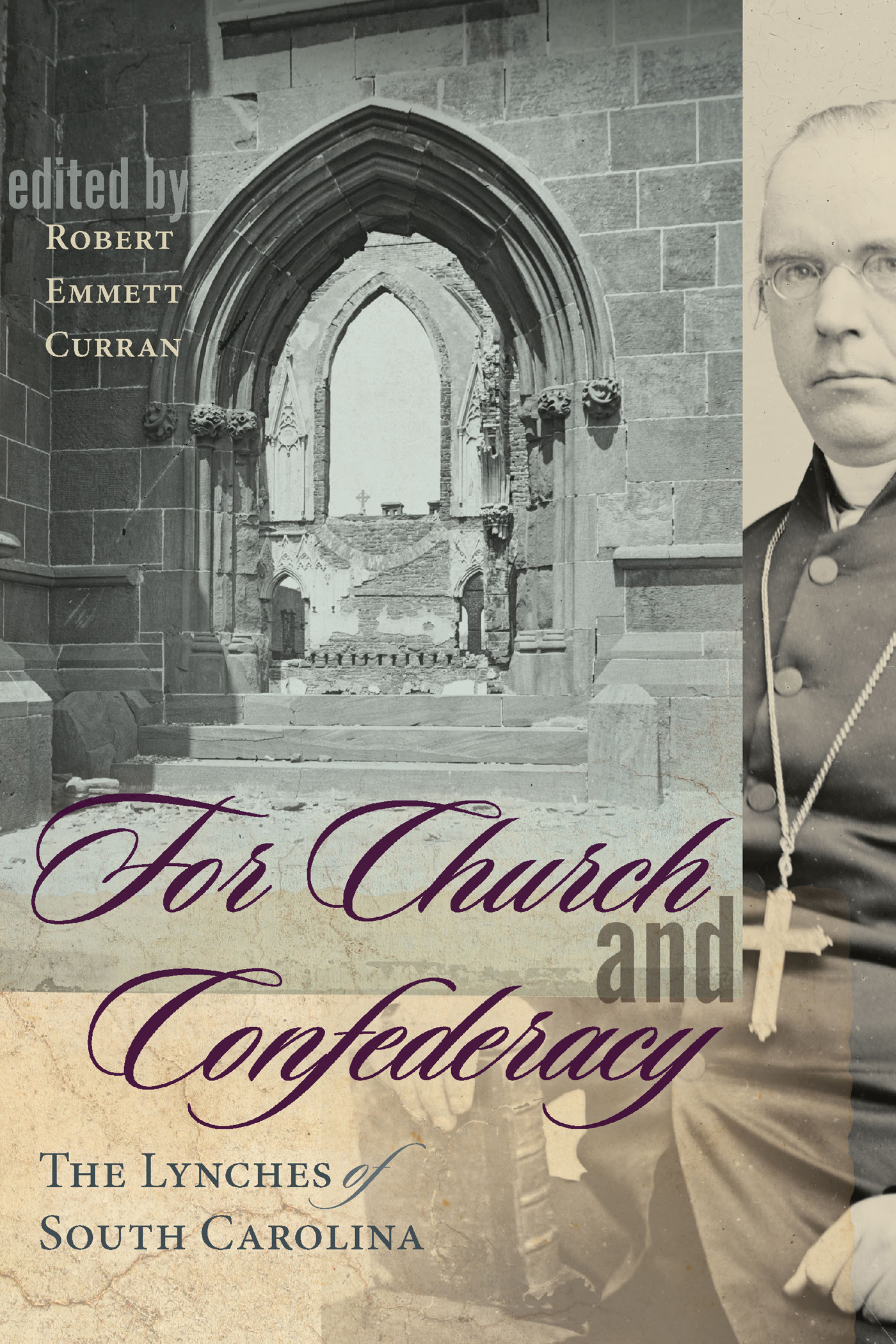

FOR CHURCH AND CONFEDERACY

For Church and Confederacy

THE LYNCHES OF SOUTH CAROLINA

EDITED BY Robert Emmett Curran

THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS

2019 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN 978-1-61117-917-0 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-64336-021-8 (ebook)

Front cover photographs: Ruins of Roman Catholic Cathedral, Charleston, South Carolina, by George Barnard; and Bishop Lynch, Brady-Handy photograph collection, courtesy of the Library of Congress

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In the course of collecting this material, I have incurred many debts, nowhere more so than with the Catholic Diocese of Charleston Archives, where the archivist, Brian Fahey, and his associate, Melissa Bronheim, did the invaluable work to make this volume possible: from locating materials, directing me to others, scanning documents, confirming sources, securing permissions, and much other assistance that greatly facilitated the production of this edition. Others to whom I would like to express my appreciation include Tricia Pyne, director, and Alison Foley, associate archivist, of the Associated Archives of St. Marys Seminary and University; Constance Fitzgerald, OCD, archivist of the Baltimore Carmel; William Kevin Cawley, senior archivist, and his assistant, Joseph Smith, of the University of Notre Dame Archives; George Rugg, curator of the University of Notre Dame Special Collections; Martha Jacob, OSU, and Sr. Cabrini, OSU, of the Ursuline Sisters of Louisville Archives; Edie Jeter of the Diocese of Richmond Archives; Timothy Meagher, director, and W. John Shepherd of the Catholic University of America Archives; Debbie Lloyd, OSU, archivist of the Ursuline Sisters of Brown County (Ohio) Archives: Gillian M. Brown, of the Catholic Diocese of Savannah Archives; and Stephanie Brooks, Library Express Leader, Eastern Kentucky University, especially for securing documents from the Library of Congress Manuscripts Division.

At the University of South Carolina Press I am particularly indebted to the anonymous reviewers. Their critiques and recommendations greatly improved this volume. Especially valuable was their identification of a number of persons who had escaped my recognition. But most of all I am grateful to Linda Fogle, assistant director for operations at the press, who inherited my manuscript in very difficult circumstances. Her experience, sound judgment, and steady encouragement were primarily responsible for bringing it into print.

Grants from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University provided me with the funds to make several visits to the archives of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston, as well as to have hundreds of documents scanned for my transcribing and annotating back in central Kentucky. For this assistance I am most grateful. Finally, to my wife, Eileen, who has graciously endured, for more than a decade now, a life she hardly anticipated when we moved here for our retirement, that of being a scholars widow, I can only offer an appreciative love for all she has put up with and for all she has meant to me and continues to mean.

INTRODUCTION

Many summers ago I was looking for a text on the Civil War to use in the History of the American South course I was preparing to offer the following spring semester. So I packed away a number of possibilities as I headed off on vacation to the deep woods of Maine, just across from Mount Desert Island. One of the volumes was The Children of Pride, Robert Manson Meyerss collection of letters of the Charles Colcock Jones family in Georgia during the Civil War era. I knew that Children had won a National Book Award but had no particular expectations about the work. But as I got into the story of the Joneses, it more and more swept me up. Even in high summer, the days proved too short (we had no electricity in the cabin we were renting) in keeping up with Charles Colcock Jones and his family as the Civil War played out through their correspondence. I remember saying to myself: This reads just like Gone With the Wind, only better! Only later did I learn that Margaret Mitchell had spent a great deal of time with the Jones collection at Tulane University when she was preparing to write her bestseller. Needless to say, I added Children to my booklist.

Three decades later I was researching a book that I hoped to write about Catholics and the American Civil War. That research took me to Charleston, South Carolina, to the Archives of the Catholic Diocese on Broad Street in the old district of the city. While looking through the papers of Patrick Lynch, Charlestons bishop during the war, the archivist, Brian Fahey, asked whether I had ever seen the correspondence of the Lynch family. He thought I might find it quite useful in tracing Catholic involvement in the war. He proceeded to bring out a calendar of Lynch family correspondence that seemed to go on and on and on. There were in fact more than 1,600 letters written over a forty-year period. Since I had but one day in Charleston, I could not really give them any attention just then, but Brian steered me to the Lowcountry Digital Library, where the South Carolina Historical Society had very conveniently scanned the correspondence between 1858 and 1866, which is where I finally had the opportunity to peruse them. It was like reliving that special summer long ago as I followed the Lynches up to the war and through it, in the many different ways in which they participated and felt the wars impact.

THE JONESES AND THE LYNCHES

The parallels between these two prominent families were immediately evident. Both the Joneses and the Lynches operated multiple plantations, in Georgia and South Carolina respectively, on which scores of enslaved African Americans labored. Both families were extraordinarily involved within their respective faith communities, with the Joneses counting three ministers in their extended family and the Lynches a bishop as well as three nuns within two generations of the nuclear family. Both counted notable members of the medical profession in their communities. Both families in their political affiliation were staunchly Democratic, but whereas political issues tended to be in the Joneses bloodstream, for the Lynches they were very much confined to the epidermis of their social lives. As the volume and frequency of their correspondence suggest, both the Joneses and Lynches were close-knit families, the Joneses encompassing a network of extended relatives, the Lynches a more intimate clan of siblings. For both families, the matriarchs were the ones providing cohesion and final authority.

If there were striking parallels between the two families, there were also important differences. The Joneses were a small nuclear family with a large network of relatives throughout Georgia. The Lynches were a typically large Irish-American family (parents and a dozen children), but they had no other kin (at least within a recognizable degree of affinity) within a thousand miles. The Joneses had deep roots in America, having been in the country for at least six generations, about as native as any Anglo-Americans in the Deep South could be.

Among the landed aristocracy of the South, wealth was a given for them. The three plantations and 130 slaves that Charles Colcock Jones possessed in Liberty County had come to him through inheritance and marriage. That wealth enabled him and his sons access to the finest academies and colleges in the North for their education and professional training. It insulated them from the need to use their professions as moneymaking operations. So Joseph Jones, a doctor, could easily boast that making money is not the end and aim of my life.

Next page