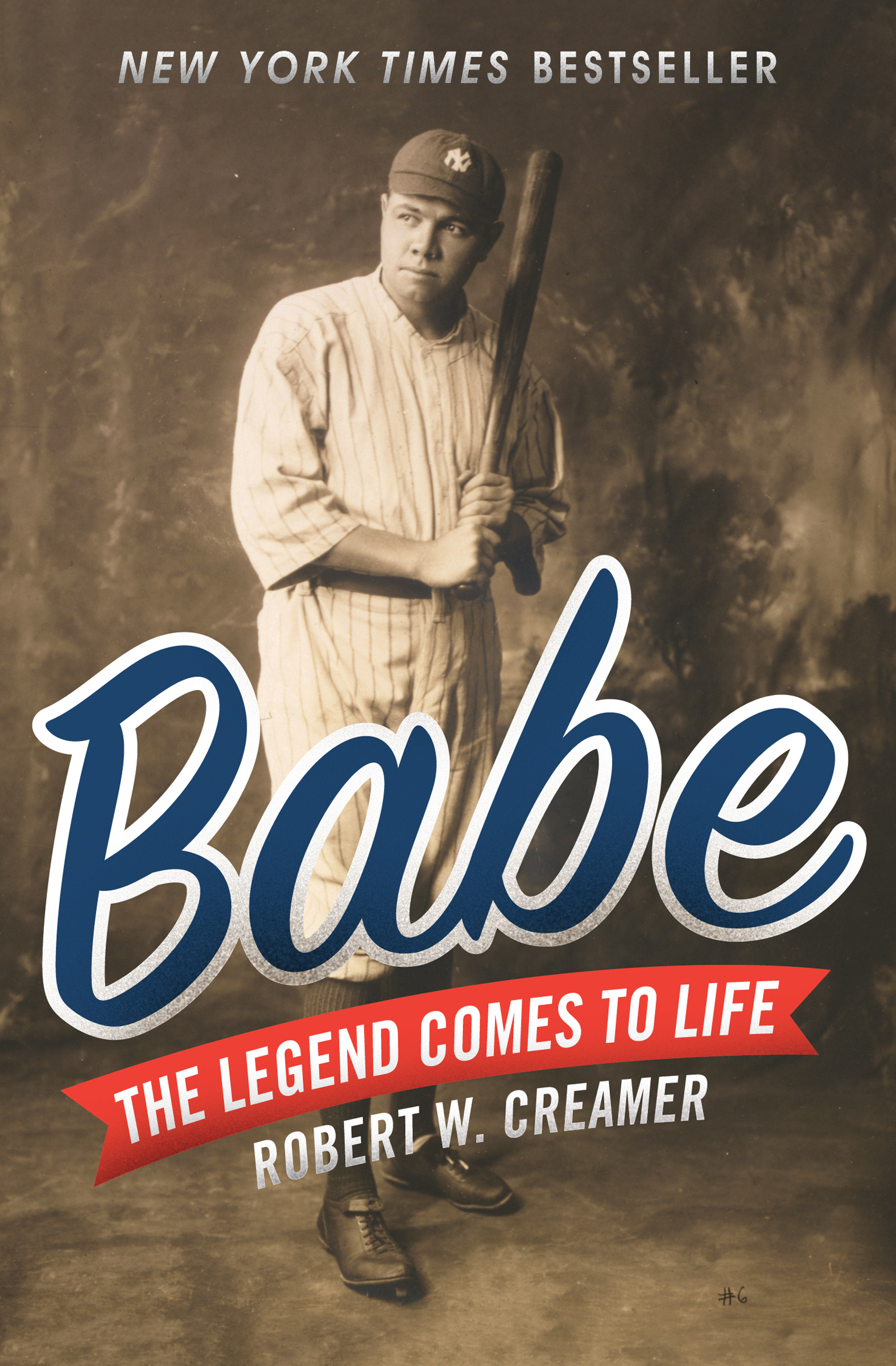

Babe

Robert W. Creamer

For

Miggy Schelz

AUTHORS NOTE

A CERTAIN FLATNESS of perspective may be evident in some of the descriptions of Ruths adventures, but I did not want to invent motive and detail when I could not be sure of the facts. I have tried to keep surmise, conjecture and amateur psychoanalysis to a minimum. In a few instances I have edited stilted dialogue from old accounts to make it sound the way it probably was spoken, but I have not imagined any conversations or thoughts. All derive from one source or another.

Some of the baseball detail may prove tedious to the casual reader, who is given permission to skip such passages. Baseball fans are expected to wade through the whole thing.

ROBERT W. CREAMER

PART ONE 18941919

CHAPTER 1

Legend and Truth:

Babe Ruth Lives

I APOLOGIZE FOR NOT having talked to everybody. There were so many. Each week I would think, There, now Ive finished with that section. Now I know all there is to know about that. And a few days later I would learn of someone new or someone I had not thought of or someone I never would have thought of, and he would have one more window on the past for me to raise. A quick insight, an illuminating moment. Pete Appleton, for instance. The only thing I remembered about Pete Appleton was that his real name was Pete Jablonski, and I was wrong about that; it turned out to be Jablonowski. I had to look up his record to learn that he had pitched in the major leagues off and on for fourteen seasons. The clipping that came to my desk had Pete Appleton telling of Ruth phoning down to a hotel lobby from his room, asking the switchboard to page any Yankee player thats around down there. Appleton, who was new to the ball club, took the call, and Ruth said, Hey, keed, how about coming up and playing some cards with me? He was lonesome, Appleton explained. He could not come downstairs to the lobby because hed be mobbed by people, especially women. This was 1933. (Where was Claire?) There was nothing in Appletons little story about booze and broads and gluttony and raising hell. Just an edgy, lonesome man in a hotel room.

And, said Appleton, He had the prettiest swing of all. The prettiest. An odd but strikingly accurate word to describe what Ruth did so much better than anyone else. Have you ever seen that old film clip of Ruth taking batting practice? If you like baseball you remember the pretty things about the gamethe individual moments of craftsmanship and, sometimes, artistry within the mathematical precision of three strikes, three outs, four balls, four bases, nine innings, nine men. Ruth, easing along at three-quarter speed in batting practice, stepping into the pitch, flicking the bat around, meeting the ball cleanly, cocking the bat back for the next pitch, is for meand maybe Pete Appletonthe epitome of baseball, its ideal expression.

This book had its genesis, I suppose, in my memory, because I saw Ruth when I was a boy. I saw him hit home runs in Yankee Stadium, and I remember that they all seemed to be a hundred feet high in the air as they passed first base. I remember watching him swing and miss, his huge torso twisting violently so that he ended up with his face more than 180 degrees around from the plate, staring intently up into the stands, right at me. God, how I remember that feeling: Babe Ruth is looking right at me. I remember him in right field one day when a little dying-quail hit began to fall into no mans land, that point of inaccessibility at the extreme range of center fielder, right fielder and second baseman, and I can still see Ruth waddling in from right field and in and in as he tried to get to the ball. (I think now that maybe the second baseman and the center fielder held up a little, giving way to the king.) He had his right arm extended, the glove held low, and after his long, inept run the ball glanced off the heel of his glove and fell safely. That was in 1933 too, when he was thirty-nine and his fat was old; I learned later that those who had played with him in his prime hated it when people like me, who saw him only in those last years, recalled him like that. They remembered when he could run (he stole fifty bases his first four seasons with the Yankees) and field and throw and do everything on a ballfield.

Correspondence followed with Peter Schwed of Simon and Schuster, in the course of which it was decided that I would attempt a thorough, detailed biography of the Babe. There had been several books written about him, all of them informative to varying degrees, but all necessarily limited in scope, one way or the other. His autobiography, done with Bob Considine and Fred Lieb, was written when Ruth was desperately ill, at a time when it was difficult for him to speak and awkward for his collaborators to press him for nitpicking details and specific information. Two unauthorized biographies appeared at about the same time, one in 1947 and the other in 1948. The first, by Tom Meany, was lively and entertaining, but it was more a colorful portrait than a biography. The second, by Martin Weldon, was earnest and detailed but contained assumptions and mistakes that were surprising in a book so thoroughly researched. Ruths widow wrote a memoir of her husband with Bill Slocum, Jr., in 1959 that shed a good deal of light on aspects of his personal life, but it degenerated into a philippic against organized baseball for its rejection of the Babe after his playing days were over. Lee Allen, the baseball historian, wrote a book for boys in 1966 that was a meticulous account of Ruths playing days but which glossed over the unsavory episodes. Daniel M. Daniel wrote an early authorized biography in 1930 that contained firsthand material. Louis J. Leisman published a 36-page pamphlet in 1956 called I Was with Babe Ruth at St. Marys that was of considerable help in understanding what Ruths boyhood was like. In 1959 Roger Kahn did a piece for Esquire that punctured some of the fatuous myths about Ruth and reaffirmed with fresh testimony the extraordinary impact and continuing hold he had on the people of his generation. By far the most revealing and rewarding work on Ruth was a novella-length soft-cover memoir written in 1948 by Waite Hoyt, who had been the Babes teammate for more than a decade during the heroic years.

What I have tried to do in this book is go beyond the gentle inaccuracies and omissions of the earlier accounts and produce a total biography, one that, hopefully, would present all the facts and myths, the statistical details and personal exuberance, the obvious and subtle things that combined to make the man born George Ruth a unique figure in the social history of the United States. For more than any other man, Babe Ruth transcended sport, moved far beyond the artificial limits of baselines and outfield fences and sports pages. As I write this, he is dead and buried for more than twenty-five years, and it is nearly forty years since he played his last major league game. Yet almost every day, certainly several times a week, you read and hear about him. As Henry Aaron moved toward Ruths career record of 714 home runs, he said, I cant recall a day this year or last when I did not hear the name of Babe Ruth. Sometimes the references come in comic profusion. When Willie Sutton was released from prison, amid the odd adulation we Americans like to give to excrescences on the fabric of society, Time

Next page