Table of Contents

AVAILABLE UP CLOSE TITLES:

Rachel Carson by Ellen Levine

Johnny Cash by Anne E. Neimark

W. E. B. Du Bois by Tonya Bolden

Ella FITZERALD by Tanya Lee Stone

Bill Gates by Marc Aronson

Jane Goodall by Sudipta Bardhan-Quallen

Robert F. Kennedy by Marc Aronson

Harper Lee by Kerry Madden

THURGOOD MARSCHALL by Chris Crowe

Elvis Presley by Wilborn Hampton

Ronald Reagan by James Sutherland

Babe RUTH by Wilborn Hampton

John Steinbeck by Milton Meltzer

Oprah WINFREY by Ilene Cooper

Frank Lloyd Wright by Jan Adkins

FUTURE UP CLOSE TITLES:

Theodore Roosevelt by Michael Cooper

For Mickey and Alan Friedman

and

Jim and Becky Rebhorn

Bleacher Buddies for life

FOREWORD

EVERY KID WHO ever picked up a baseball knows the name Babe Ruth. Even those who are not quite sure what records he held or what he did to achieve them know that the Babe was considered the best ever to play the game. Around the world, even in countries where baseball is not played, people know that Babe Ruth was the epitome of excellence.

Few, however, know who the man behind the legend really was. They know he was the home-run king, the Bambino, the Sultan of Swat. But the story of who he was before he became all those things is clouded in mystery and has been sugarcoated by generations of sportswriters and fans. As a result, there are probably more stories about Babe Ruth than about any other sports figure of the twentieth century. It was widely reported, for example, that he was an orphan who was determined to find his way out of poverty through baseball. The truth, as always, is more complicated.

George Herman Ruth was not an orphan. He was a bad kid from a bad neighborhood whose parents placed him in a Catholic reform school for delinquents and orphans at the age of seven. He discovered baseball almost by chance because one of the Xaverian Brothers who ran the school thought it could help him straighten out his life, and little George fell in love with the game. In fact, nobody loved the game more and nobody played it better.

As a boy growing up, I played a lot of baseball on vacant lots or school playgrounds with my neighborhood friends. We used book satchels or rocks or whatever we could find for bases, and we rarely had more than one ball and one bat and half a dozen gloves to share for both sides. Although all of my friends had favorite players from major-league teams (mine was Willie Mays of the then New York Giants), the one player who was regarded by everyone as the all-time greatest was Babe Ruth.

Although I soon realized I was not going to be a professional baseball player, my love of the game and my fascination with the Babe only grew. His ghost haunted baseball season after season. He remained the standard against which all players who followed him were measured. Who was the boy who fought his way out of a Baltimore slum to become the idol of every kid in America?

The only way to find an answer was to write his life story. In the process I discovered a man who lived hard and played hard and who was even bigger than his myth.

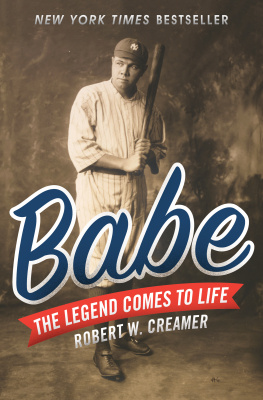

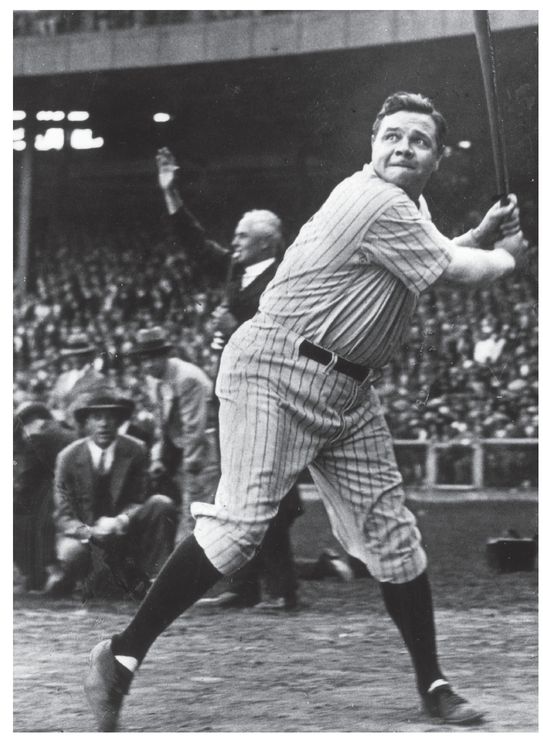

Babe Ruth at batting practice in 1927. He copied his famous swing from Brother Matthias at St. Marys in Baltimore.

INTRODUCTION

On February 14, 1914, George Ruth was outside St. Marys Industrial School for Boys in Baltimore, on one of the schools two playgrounds, when a big limousine drove through the main gates.

It was cold that St. Valentines Day. It had been snowing, and the Big Yard, as the playing field for the older boys at St. Marys was known, was icy and slippery. With no organized sport planned for their recreation period on that frosty day, George, who had just turned twenty the week before, and several of the other boys were running and sliding on the frozen turf, killing time until they had to go back inside. They noticed the big car as it drove up to the front entrance of the school, but it didnt stop their frolicking on the ice.

Inside the car were three menFritz Maisel, a native of Baltimore who played baseball for the New York Yankees and who owned the car; Brother Gilbert, the baseball coach at St. Josephs, a neighboring Roman Catholic school and a rival of St. Marys; and Jack Dunn, the owner of the Baltimore Orioles, then a minor-league team. They got out and went into the building.

Two of the men were there on a mission. Dunn was looking for a pitcher for his baseball team, which was scheduled to start spring training in a couple of weeks. Brother Gilbert wanted to make sure Dunn didnt steal his own ace left-hander at St. Josephs. Maisel was basically along for the ride, especially since it was his car.

Dunn had first heard about George Ruth from a friend named Joe Engel, a former player for the Washington Senators who had seen George pitch for St. Marys in a school exhibition game. Then Dunn heard the same name from Brother Gilbert when he went to scout a possible pitcher at St. Josephs. Brother Gilbert, wanting to keep his own player in school and pitching for St. Josephs, began to extol the natural talent of a kid named Ruth over at St. Marys. Dunn decided it was time to see for himself.

The trio first went to the office of Brother Paul, who was the superintendent of the school, and chatted while they waited for Brother Matthias, a huge yet soft-spoken man who stood six foot six, weighed 250 pounds, and was St. Marys physical-education director. Dunn learned from Brother Paul that Georges father was still alive, but that the school had legal responsibility for his affairs until he was twenty-one.

When Brother Matthias joined them, Dunn asked him whether the boy could play ball.

Ruth can hit, Brother Matthias said, never one to elaborate.

Can he pitch? Dunn persisted. After all, Dunn was in the market for a pitcher.

Sure, Brother Matthias replied vaguely. He can do anything.

Dunn decided he wasnt going to get much more information out of Brother Matthias and asked to see George. They found him on the Big Yard, wearing overalls, and Dunn asked someone to find a baseball.

Brother Gilbert began to get nervous. He knew Dunn wanted a pitcher, and he had touted this George Ruth as a terrific pitching prospect. But the truth was that Brother Gilbert had never seen George pitch. In fact, the only time he had seen George play was in one game between St. Marys and St. Josephs, which St. Marys had won 6-0. In that game, George had played catcher.

There are various accounts of what exactly took place on that cold day in February 1914. In a ghostwritten 1928 autobiography titled Babe Ruths Own Book of Baseball, Ruth said Dunn had me pitch to him for a half hour I guess, talking to me all the time, and telling me not to strain and not to try too hard.

At the end of it, Dunn and the other men went back into the school office, and a short time later they sent for young George. Dunn didnt waste any time.

How about it, young man, do you want to play baseball? he asked George.