Table of Contents

FROM THE PAGES OF

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Raskolnikov was not used to crowds, and, as was said previously, he avoided society of every sort, especially recently. But now all at once he felt a desire to be with other people. Something new seemed to be taking place within him, and with it he felt a sort of thirst for company. (page 13)

Man grows used to everything, the scoundrel! (page 29)

Can it be, can it be, that I will really take an axe, that I will strike her on the head, split her skull open... that I will tread in the sticky warm blood, break the lock, steal and tremble; hide, all spattered in the blood... with the axe... Good God, can it be? (page 60)

Fear gained more and more mastery over him, especially after this second, quite unexpected murder. (page 80)

At first he thought he was going mad. A dreadful chill came over him; but the chill was from the fever that had begun long before in his sleep. Now he suddenly started shivering violently, so that his teeth chattered and all his limbs were shaking. (page 89)

You think I am attacking them for talking nonsense? Not a bit! I like them to talk nonsense. Thats mans one privilege over all creation. Through error you come to the truth! (page 194)

Porfiry Petrovich was wearing a dressing-gown, very clean clothing, and trodden-down slippers. He was about thirty-five, short, stout, even corpulent, and clean shaven. He wore his hair cut short and had a large round head which was particularly prominent at the back. His soft, round, rather snub-nosed face was of a sickly yellowish color, but it also had a vigorous and rather ironical expression. It would have been good-natured, except for a look in the eyes, which shone with a watery, sentimental light under almost white, blinking eyelashes. The expression of those eyes was strangely out of keeping with his somewhat womanish figure, and gave it something far more serious than could be guessed at first sight. (page 238)

Extraordinary men have a right to commit any crime and to transgress the law in any way, just because they are extraordinary.

(page 247)

Legislators and leaders, such as Lycurgus, Solon, Muhammed, Napoleon, and so on, were all without exception criminals, from the very fact that, making a new law, they transgressed the ancient one, handed down from their ancestors and held sacred by the people, and they did not stop short at bloodshed either. (page 247-248)

A minute later Sonia, too, came in with the candle, put down the candlestick and, completely disconcerted, stood before him inexpressibly agitated and apparently frightened by his unexpected visit. The color rushed suddenly to her pale face and tears came into her eyes... She felt sick and ashamed and happy, too. (page 301)

Must I tell her who killed Lizaveta? (page 385)

Who is the murderer? he repeated, as though unable to believe his ears. You, Rodion Romanovich! You are the murderer, he added almost in a whisper, in a voice of genuine conviction. (page 433)

Youre a gentleman, they used to say. You shouldnt hack about with an axe; thats not a gentlemans work. (page 517)

BARNES & NOBLE CLASSICS

NEW YORK

Published by Barnes & Noble Books

122 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10011

www.barnesandnoble.com/classics

Dostoevskys Prestupleniye i nakazaniye was originally published in Russian in 1866.

Constance Garnetts translation of Crime and Punishment was first published in 1914.

Published in 2007 by Barnes & Noble Classics with new Introduction,

List of Characters, Notes, Biography, Chronology, Inspired By,

Comments & Questions, and For Further Reading.

Introduction, List of Characters, and For Further Reading

Copyright 2007 by Priscilla Meyer.

Note on Fyodor Dostoevsky, The World of Fyodor Dostoevsky and

Crime and Punishment , Notes, Inspired by Crime and Punishment ,

Comments & Questions, and revisions to the Constance Garnett

translation by Juliya Salkovskaya and Nicholas Rice

Copyright 2007 by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,

recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the

prior written permission of the publisher.

Barnes & Noble Classics and the Barnes & Noble Classics

colophon are trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Crime and Punishment

ISBN-13: 978-1-59308-081-5 ISBN-10: 1-59308-081-6

eISBN : 978-1-411-43201-7

LC Control Number 2004102189

Produced and published in conjunction with:

Fine Creative Media, Inc.

322 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10001

Michael J. Fine, President and Publisher

Printed in the United States of America

QM

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FIRST PRINTING

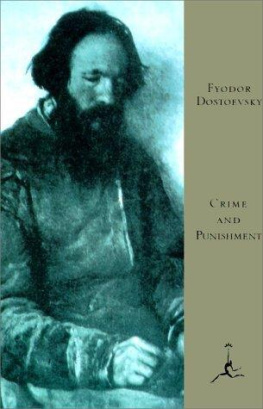

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was born in Moscow on October 30, 1821. His mother died when he was fifteen, and his father, a former army surgeon, sent him and his older brother, Mikhail, to preparatory school in St. Petersburg. Fyodor continued his education at the St. Petersburg Academy of Military Engineers and graduated as a lieutenant in 1843. After serving as a military engineer for a short time, and inheriting some money from his fathers estate, he retired from the army and decided instead to devote himself to writing.

Dostoevsky won immediate recognition with the 1846 publication of his first work of fiction, a short novel titled Poor Folk . The important Russian critic Vissarion Grigorievich Belinsky praised his work and introduced him into the literary circles of St. Petersburg. Over the next few years Dostoevsky published several stories, including The Double and White Nights. He also became involved with a progressive group known as the Petrashevsky Circle, headed by the charismatic utopian socialist Mikhail Petrashevsky. In 1849 Tsar Nicholas I ordered the arrest of all the members of the group, including Dostoevsky. He was kept in solitary confinement for eight months while the charges against him were investigated and then, along with other members of Petrashevskys group, was sentenced to death by firing squad. At the last minute Nicholas commuted the sentence to penal servitude in Siberia for four years, and then service in the Russian Army. This near-execution haunts much of Dostoevskys subsequent writing.

The ten years Dostoevsky spent in prison and then in exile in Siberia had a profound effect on him. By the time he returned to St. Petersburg in 1859, he had rejected his radical ideas and acquired a new respect for the religious ideas and ideals of the Russian people. He had never been an atheist, but his Christianity was now closer to the Orthodox faith. While in exile he had also married.

Dostoevsky quickly resumed his literary career in St. Petersburg. He and his brother Mikhail founded two journals, Vremia (1861-1863) and Epokha (1864-1865). Dostoevsky published many of his well-known post-Siberian works in these journals, including The House of the Dead , an account of his prison experiences, and the dark, complex novella Notes from Underground.

The next several years of Dostoevskys life were marked by the deaths of his wife, Maria, and his brother Mikhail. He began to gamble compulsively on his trips abroad, and he suffered from bouts of epilepsy. In 1866, while dictating his novel The Gambler to meet a deadline, he met a young stenographer, Anna Snitkina, and the two married a year later. Over the next fifteen years Dostoevsky produced his finest works, including the novels Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868), The Possessed (1871-1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1879-1880). His novels are complex psychological studies that examine mans struggle with such elemental issues as good and evil, life and death, belief and reason. Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky died from a lung hemorrhage on January 28, 1881, in St. Petersburg at the age of fifty-nine.

Next page