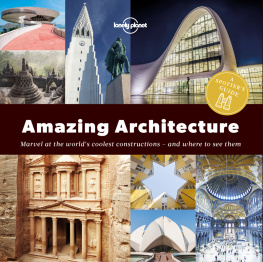

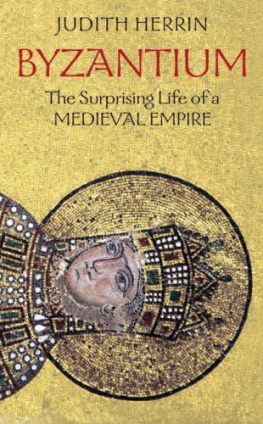

As the Roman Empire declined and fell, a new empire was born - the Byzantine. Its birth was a turning point in history; its life was to span 1,100 years. Rooted in the classical traditions of Greece and Rome, the Byzantine Greeks rejected the dying pagan gods of those cultures and evolved a living Christian civilization. Their capital was the New Rome, Constantinople; their sacred shrine, succeeding the temple of the Pantheon, was the Church of Hagia Sophia, the Holy Wisdom, consecrated to the one God alone. This great church rose in the sixth century - a symbol of Christs wisdom; a masterpiece of volume, scale, and architectural style; an embodiment of the power, grandeur, and spirit of a mighty empire, uniting East with West.

Hagia Sophia appears today much as the Byzantine historian Procopius described it more than fourteen centuries ago: [A] spectacle of marvellous beauty, overwhelming to those who see it, but to those who know it by hearsay altogether incredible. For it soars to a height to match the sky, and as if surging up from the other buildings it stands on high and looks down on the remainder of the city.... Both its breadth and its length have been so carefully proportioned, that it may not improperly be said to be exceedingly long and at the same time unusually broad. And it exults in an indescribable beauty. For it proudly reveals its mass and the harmony of its proportions, having neither any excess nor deficiency, since it is both more pretentious than the buildings to which we are accustomed and considerably more noble than those which are merely huge, and it bounds exceedingly in sunlight and in the reflection of the suns rays from the marble.

Noting that the interior of the great church seemed to be illuminated not only from without but by a radiance from within, Procopius declared:... whenever anyone enters this church to pray, he understands at once that it is not by any human power or skill, but by the influence of God, that this work has been so finely turned.

The interior is described in equally lyrical terms by a contemporary Byzantine poet, Paul the Silentiary: Whoever raises his eyes to the beauteous firmament of the roof, scarce dares to gaze on its rounded expanse sprinkled with the stars of heaven, but turns to the fresh green marble below, seeming as it were to see the flower-bordered streams of Thessaly, and budding corn, and woods thick with trees; leaping flocks too and twining olive-trees, and the vine with green tendrils, or the deep blue peace of summer sea, broken by the plashing oars of sea-girt ship. Whoever puts foot within the sacred fane, would live there, for ever, and his eyes well with tears of joy.

To Michael of Thessalonica, a twelfth-century scribe, the church was a tent of the heavens, which man, indeed, has set up, although God has surely taken part in the work. Within its triple doors, symbolizing the Holy Trinity, the building lies open forming an immense space, having a hollowness so capacious that it might be pregnant with many thousands of bodies and a height so great as to turn the head, and make the eyes stop still as it were at the zenith.

According to this Greek chronicler, the gilded roof of the church flashed in the sunlight with such brilliance that the gold seemed to flow from the dome in a molten stream. Precious metals had also been lavished on the interior of the church. The Holy Table, or altar, was of gold. Silver too abounded - 40,000 pounds of it in the sanctuary alone. The screen and the canopy above the altar were of silver, and the stalls of the priests were plated with silver. Thus enriched, the church was dedicated by Emperor Justinian on December 27, 537.

That was a ceremony to be repeated each year on the same date for nine centuries to come. The emperor led the way into the great church, where, in the words of an anonymous recorder, the first gleam of light rosy-armed driving away the great shadows leapt from arch to arch and all the princes and people with one voice hymned their songs of prayer and praise. Hand in hand with the patriarch, Justinian proceeded down the nave, prostrated himself before the altar, and entered the sanctuary. There he kissed the holy chalices, the golden patens, the corporal cloth, and the holy gilded cross - and there he played his role in the sacred drama of the Divine Liturgy.

On the day of this historic inauguration, Justinian emerged in state from his palace in a four-horse chariot. He sacrificed 1,000 oxen, 6,000 sheep, 600 stags, and some 10,000 birds before giving 30,000 bushels of meal to the poor and needy. Accompanied by the patriarch, he then proceeded to the church. Entering its royal gates, the emperor released the patriarchs hand, which he had been holding, and hastened on alone into the ambo. Extending his arms toward heaven, he cried, Glory to God, Who has deemed me worthy of fulfilling such a work. O Solomon, I have surpassed thee.

Justinians proud declaration was approved by many contemporaries. Paul the Silentiary compared the church to a pharos, a spiritual lighthouse: The sacred light cheers all: even the sailor guiding his bark on the waves, leaving behind him the unfriendly billows of the raging Pontus, and winding a sinuous course amidst creeks and rocks... does not guide his laden vessel by the light of Cynosure, or the circling bear, but by the divine light of the church itself.

The sea, Procopius notes, surrounds Constantinople like a garland. From the site of its former acropolis, the great domed monument of Hagia Sophia commands the waves. Set on a jutting triangular headland that has long been a focal point of world geography, the city confronts the confluence of two seas, north and south, and the meeting of two continents, east and west. Through the narrow, swift-flowing straits of the Bosporus (in English the Ox Ford), the waters flow south from the Black Sea (the classical Euxine washing the Pontic shores) into the Sea of Marmara (the classical Propontis), and then out through the strait of the Dardanelles into the Aegean and Mediterranean seas beyond. Between the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara, there curves inland a long, narrow natural harbor known as the Golden Horn. Shaped like the horn of an ox or stag, it became golden, as historian Edward Gibbon expresses it, from the riches which every wind wafted from the most distant countries into the secure and capacious port of Constantinople.

The ancient Greeks were the first people to develop these trade routes. Following Jason and his Argonauts, who sailed up the Bosporus into the Black Sea to seek the Golden Fleece - and following Agamemnon and his Achaeans, who fought the Trojans for control of the Hellespont - there came, in the course of recorded history, groups of seafaring colonists from the Greek seaport of Megara. The first of them settled on the Asian shore of the Bosporus, founding a colony at Chalcedon. Legend relates that the second, preparing to set forth around 658 BCE under a leader named Byzas, first consulted the oracle at Delphi on the choice of a site. Byzas was advised to settle opposite to the land of the blind men. Correctly interpreting this cryptic phrase, he founded his colony on the European shore, across the Bosporus from Chalcedon. In their blindness, the earlier colonists had established their settlement on a bay beset by winds, ignorant of the superior advantages of the secure harbor opposite, made by nature never to be stormy. There the city of Byzantium was built.

Thus, from the first, geography conditioned Byzantiums history. The colony founded by Byzas evolved from a Greek trading settlement into the vital eastern nexus of the Roman Empire. At the end of the second century CE, the city was extensively rebuilt by Septimius Severus. In the following century, Diocletian divided the empire into two and ruled over its eastern part from Nicomedia, a port at the head of a gulf on the Asian shore of the Sea of Marmara. Constantine the Great, who had served under Diocletian as a youth, reunited the two parts in CE 324, but decided to rule over both from a new eastern capital. Rejecting Nicomedia and toying only briefly - and perhaps apocryphally - with the notion of founding his capital on the site of ancient Troy, Constantine soon settled on Byzantium - whose strategic advantages he was quick to perceive. According to legend, he was encouraged by a flock of eagles that descended upon a prospective site near Chalcedon, seized the emperors stores and measuring tapes in their claws, and flew with them across the Bosporus to the city of Byzas.

Next page