No Way But Gentlenesse

No Way But Gentlenesse

A memoir of how Kes, my kestrel,

changed my life

Richard Hines

For Jackie, John and Katie

There is no way but gentlenesse to redeeme a Hawke

Edmund Bert, An Approved Treatise of Hawkes and Hawking, 1619

CONTENTS

In February 2012 I walked to the ruins of Tankersley Old Hall, a sixteenth-century mansion set in farmland close to my home in South Yorkshire. It was a cold overcast afternoon with drizzle in the air, and as I stood there my eyes went up to the high, crumbling ledge in the wall before me. The stones which had once surrounded the nest had fallen away, but in 1965 that was where my first kestrel had spent the first month of her life.

Id kept the kestrel, which Id called Kes, in a Second World War air raid shelter in my older brother Barrys garden. One evening, Barry told me he had come up with an idea for his second novel, a story about a lad named Billy Casper who trains a kestrel called Kes. The book, A Kestrel for a Knave, became a Penguin Twentieth-Century Classic and was made into the film Kes, directed by Ken Loach. In one scene Billy calls his kestrel to the glove in the very field in our mining village where, forty-seven years ago, I trained and flew my own kestrel, Kes.

Two other kestrels that I trained also came from that high ledge, hatching from their reddish-brown blotched eggs. I could remember how, once, my excitement had turned to despair when I reached into the nest hole. Empty, I had thought, cursing the fact I was too late, that all the young kestrels must have fledged. Yet when I reached in further, burying my arm shoulder-deep in the stonework, a gasping young hawk had lashed at my hand with its talons.

Today, almost half a century later, a kestrel called: kikiki... kikiki... I could see his blue head and tail, as with fast, shallow wingbeats the male kestrel flew out of the ruins of Tankersley Old Hall and landed on a telegraph pole. Moments later, he launched into flight again and then hovered over a verge of tall grasses beside the cart track opposite the ruined Hall. His long wings flickering, his tail fanned, and his head looking down, he hovered in the air, dropped a few feet, hovered again, then, closing his wings, plunged into the tall vegetation with his yellow legs outstretched. A minute or two later he flew up and over a hedge in the direction of the pit village where Id been brought up, half a mile away across the fields and meadows.

Turning back to gaze at the nest ledge I wondered how my life might have turned out if kestrels hadnt nested there and I hadnt trained Kes. Back then, in the mid-1960s, I could never have guessed my experiences would spark an obsession for hawks that would transform my life.

... you must by kindness make [the hawk] gentle and familiar with you...

Nicholas Cox, The Gentlemans Recreation, 1674

I was born in 1945, and brought up in Hoyland Common, five miles south of the town of Barnsley in South Yorkshire. Rockingham Colliery was the reason for the existence of the village. Had things turned out differently in 1875 the site of the village might still be farmland today. In March of that year, as the pit shaft of Rockingham Colliery was being sunk, gas ignited by the blasting set a seam of coal on fire and sent flames leaping into the sky. If relays of men hadnt rhythmically pumped water into the shaft and quenched the flames, the colliery would have been destroyed and the village of Hoyland Common wouldnt have existed.

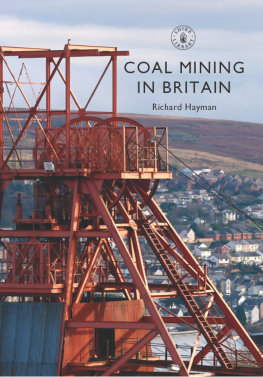

From our small rented terraced stone cottage with its low ceilings and deep windowsills I could see Rockingham Collierys winding gear, half a mile away across the fields. Silhouetted against the sky, the winding gear consisted of two large black wheels that turned as the cables holding the cage, a lift, sent clean-faced miners or empty pit tubs the small trucks which carried coal plunging to the depths. Later they hauled the cage back up again, the miners faces now black with coal dust and the pit tubs full of coal. For a place so embedded with coal dust the irony is that no part of the pit village, with its streets of stone and brick Victorian terraced houses, was more than a few hundred yards away from the fields of crops, grazing cows or flower meadows which surrounded it. The floor of the Little Wood, which was a stones throw away from the colliery slag heap, was covered with bluebells in spring. Sometimes as I lay in bed I could hear lapwings calling peewit... peewit in the night, and on spring mornings I would wake to the song of skylarks.

Our terraced cottage had no bathroom and I can remember having my baths in a tin bath in front of a blazing coal fire when I was little. My mother, who had shoulder-length dark, wavy hair and strikingly blue eyes, seemed to be moved by my vulnerability as I sat with my eyes shut tight, while waiting for her to rinse the soap from my hair. She would dip my fingers into the large pan of clean warm water, before saying, Dont ever let anyone pour water on your head, without you first checking it isnt too hot, and only rinsed my hair after Id confirmed the water was the right temperature. Bath time was the only time my mother was openly affectionate, although I know she must have occasionally felt affection towards me when I was asleep, because some mornings Id wake and find lipstick on my cheek. Showing affection seemed to embarrass my mother, but my dad, with his brushed-back dark wavy hair, dark eyebrows and gentle blue eyes, was the opposite and openly showed his emotions. The first two or three days of my life, before Mother returned home, had been spent in a maternity home in a nearby village. The rules didnt allow Dad to visit his newly born son. Instead, Mother held me up to a window, and as Dad stood outside in the grounds, his eyes filled with tears. When I was at infant and junior school I loved it when Dad returned home from the night shift at the colliery. After hed greeted me with a smile and All right, son? hed cook my breakfast while I sat in my pyjamas reading the Dandy or Beano. Our rented cottage not only lacked a bathroom, there was no lavatory either. So we had to walk about thirty yards to use a shared lavatory in someone elses backyard. That was our life until 1955, when one momentous day, along with Barry, who was six years my senior, I helped our parents carry all our furniture out of the terraced cottage, then further up Tinker Lane. Our new semi-detached and stone-fronted house had been built in the 1880s. My parents bought it for three hundred and fifty pounds and added a bathroom and indoor lavatory.

I can recall an awful occasion from around this time, when Dad had been working the morning shift and Id returned home from school to find a neighbour sitting in our house waiting for me. She told me Dad had had an accident at the colliery and Mother was at the hospital with him. Mother eventually returned home white-faced from visiting the hospital, and later I overheard her telling the neighbour that my dad had been shovelling coal on his hands and knees when a lump of muck a large piece of coal or rock had fallen on him, pinning my dads chest to the floor and breaking his back. Luckily the doctors diagnosis was wrong. It turned out that Dads back wasnt broken after all, and he was transferred from hospital to a miners rehabilitation home in Firbeck, a village on the Yorkshire/Nottinghamshire border. Those weeks without Dad were awful and I recall running up to greet him on the day he came in through the door, smiling and carrying a suitcase and a wooden lampstand hed made in the miners rehabilitation home. Soon he was back working on the coalface deep underground. The pit would continue to take its toll of lives.

Next page