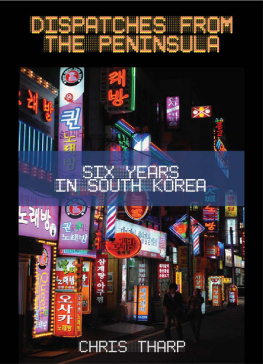

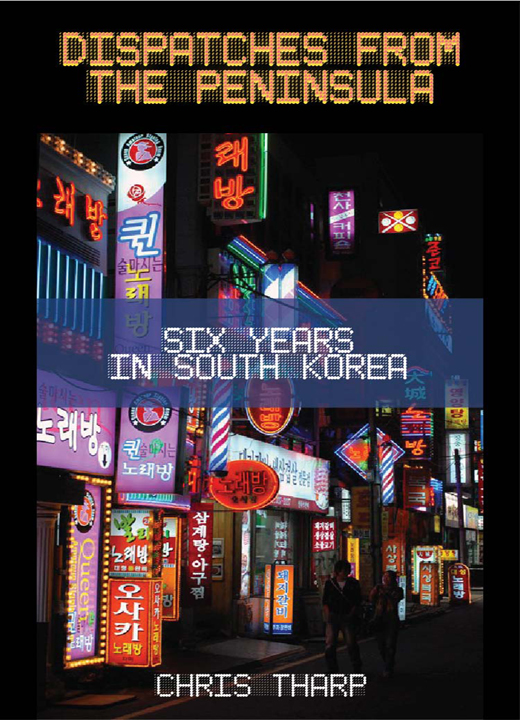

Dispatches from the Peninsula

Six Years in South Korea

By Chris Tharp

Praise for

Dispatches from the Peninsula

Tharp is like some punk-rock Huck Finn, as aware and humane as he is blithely non-PC, drama springing up around him with every choice he makes: another country, another drink, another thought he maybe should have kept to himselfbut his brain is bigger than his mouth, and Dispatches from the Peninsula gives us the whole show. And somehow, amid all its intelligence and humor, the book packs a deeper wallop too, as a serious meditation on the lifelong experiment of growing up.

Lawrence Krauser, author of Lemon, The Joy of Google, and The Day in Question

Tough and true is Tharps journey in South Korea. I found myself back there, welcoming anew Koreas wonder, her wrangle, the distinct spirit of the peninsula and her people. All along the way, Tharp is an observant and steady companion.

Cullen Thomas, author of Brother One Cell

Dispatches from the Peninsula

Six Years in South Korea

By Chris Tharp

Published by Signal 8 Press

An imprint of Typhoon Media Ltd

Smashwords Edition

Copyright 2011 Chris Tharp

eISBN: 978-988-15161-5-2

ISBN: 978-988-15161-1-4

Typhoon Media Ltd: Signal 8 Press | BookCyclone

Hong Kong

www.typhoon-media.com

www.bookcyclone.com

www.signal8press.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for brief citation or review, without written permission from Typhoon Media Ltd.

Cover design: Clarence Choi

Cover and author photos: Will Jackson

For Chaunce and Glo

Contents

CHAPTER 1: NEON CROSSES

The first thing I noticed was the crossesred, lit-up crossesattached to the steeples of the citys many churches, floating in the darkness of the early August evening. They popped out in contrast to all the restaurant and shop signs in the blocky circles, squares, and right angles of the Korean script known as Hangul. There were churches everywhere, each displaying its own garish cross, reminding you of Christs sacrifice with a burning, neon fervor. Despite my agnosticism, I found all this incandescent evidence of Christianity somehow reassuring: At least some of them worship the same God as us. This assuaged my Western anxiety, andin my mindreduced the likelihood of me being maimed, killed, or eaten.

The bus I traveled on was a limousine bus, though there was neither a wet bar nor a sunroof (not to mention any smooth surfaces off of which you could snort cocaine), and it wasnt stretched out longer than any bus Id ridden on before. It was nice, but unless youre a touring rock band, there are very few ways you can dress up a bus. This bus simply served as transportation from the airport to several key points in the city of Busan, South Koreas largest seaport and second biggest metropolis and my new home. Calling the bus a limousine was fine with me: I could imagine I that was riding in style and forget the fact that, despite having traveled over the worlds largest ocean to a country where I didnt even know the word for hello, no one had bothered to pick me up at the airport.

The bus careened through the car-clogged city at obscene speeds, only to jerk to a stop within minuscule distances, sending bags sliding and causing my head to slam into the seat in front of me. Despite the trappings of affluence on the roadshiny new cars, high-definition digital reader boards, working traffic lights, a pothole-free surfaceKorean bus drivers drove Third-World style. Later I would find that the drivers of the blue and orange city buses are worse: they pilot with even more violence, and the smashed-together payloads of standing passengers just endure the jostling without complaint. At least I had the privilege to sit, though Im sure my fingers left divots in the plastic armrests as the driver barreled through the crowded streets. He smoked skinny cigarettes and loudly sang along with Korean trot music, its mournful vibratos and Casio keyboard cha-cha beats blaring from the speakers. Korean bus drivers, it seemed, were culturally mandated to drive like meth addicts on their way to a score.

As we shot up the highway, over the Nakdong River and away from the airport, I took in the approaching skyline. A ridge of medium-sized skyscrapers reached up in front of an imposing mountain. I took this to be the core of the city, the downtown. Of course I soon realized that these werent skyscrapers as I knew them, but rather a cluster of apartment blocks, and that we were still deep in the suburbs. This first visible line of urbanization was merely a sliver of a disconcertingly long city that snaked its way along the coast, up valleys, and between rises of ancient fortress-topped mountains. Korea is an extremely mountainous country, with only about thirty percent of its land suitable for building. The cramped panorama of apartment towers that jutted in front of me served as a testament to this. Every bit of available space was utilizedpeople were literally stacked on top of each otherso it was crowded. With the exception of the crosses, this was Asia as I had imagined it. I was in Korea, and it was already weird.

Jimmy, my local contact, didnt want to come pick me up at the airport. Something about traffic, he had muttered in halting English a few days before, over a trans-Pacific phone connection. We had spoken one last time before I boarded the plane to fly over and work in the language school where he served as vice-director. Like many Koreans who speak any English, he had adopted an English nickname, drawing out the second syllable as he spoke it: Hello, this is Jimeeeeee. I had called him from the airport, deftly navigating the forlorn payphone (Korea has one of the highest rates of cell phone ownership on the planet; its amazing that payphones even exist) and receiving instructions on which bus to catch. I was to get off at the Marriott Hotel in Busans famous Haeundae Beach, porter my bags (a years worth of shit) to the nearest payphone, give him a call, and wait for his arrival. Upon stepping off the plane, this was the warm embrace I was wrapped in.

After over an hour of blazing through the city, the limousine bus arrived at Haeundae Beach, a one-and-a-half-kilometer stretch of imported sand, hotels, and raw fish restaurants that is one of Koreas most popular tourist attractions. In the summer, the hordes descend southward from Seoul, fleeing the choking combination of smog and humidity that smothers that city during the hottest months, turning the beach into a wall of bodies and parasols. As we pulled up to the Marriott, I took in the surrounding buildings: most were brightly-lit love motels, with motifs of palm trees, sexy girls, and ocean waves plastered on the side. One architectural monstrosity loomed prominent: it housed a Bennigans, TGI Fridays, and Starbucks. Sixteen hours of traveling and here it was, the mysterious Orient, splayed out before me in its very Western glory. Perhaps I wasnt as far from home as I thought.

Unlike most Koreans, Jimmy drove an economy-sized car. Koreans are smallish people living in a smallish country, but the cars they drive dont reflect this. Most drive large, Korean-made, four-door sedanswith the odd SUV, even. But Jimmy rolled up in a Hyundai Tico, the Korean equivalent of the old Geo Metro or AMC Gremlin. When he got out to help me with my bags, I saw that he was shockingly tall and thin as a famine victim, with small glasses and a very reasonable haircut in the style of most East Asian middle managers.

Next page