A New Yorker cartoon from 1998 showed a beggar on the streets of the city, holding a sign that says Expert on Russia. For most of the early twenty-first century Russia was a niche interest, pushed off the front pages by the War on Terror, the Great Crash, the Rise of China. Economically it was an aberration and politically, compared to the Cold War, an irrelevance. Russian university departments closed; the secret services culled their Russian speakers; development agencies pulled, or were pushed, out. Russia just wasnt in.

How things have changed! Writing in mid-2017, barely a day goes by without Russia on the front page: invading Eastern European countries; hacking the US election; subverting the Liberal World Order; splitting Europe; bombing Syria to smithereens while (allegedly) bamboozling the world with its next-generation, full-spectrum, hybrid war and weaponized propaganda. Russian President Vladimir Putin is the international Bond villain of the age (he must be delighted). The secret services are busy hiring Russian speakers again. Today everyone pretends to be an expert on Russia though they may never have visited the country or speak the language. Russia is most definitely in: seen either as the greatest evil in the world, or, for a new generation of far-right worshippers, the great hope.

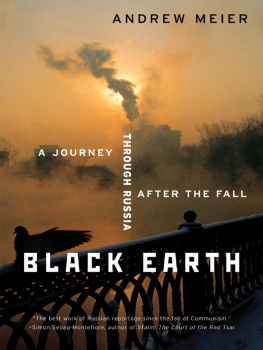

What is missing among all the Russomania, Russophobia and Putinophilia is any sense of what the Russian people are like. They tend to be reduced to either authoritarian-loving dupes dumb enough to believe their lying leaders every word, or to passive victims broken into submission. Charlotte Hobsons Black Earth City, a memoir of her year in Russia in the early 1990s, is a sublime lesson in putting away ones preconceptions.

Hobsons great talent is to bring people and places alive in a few lines. Her place is Voronezh, the provincial southern capital home, over the centuries, to exiles and industrialists, a frontier town for chancers and those running away from something, and for foreign students who wanted to experience something more exotic than Moscow or St Petersburg. Hobson arrived in time to catch the last moments of the Soviet Union and stayed for the all-defining days which came after. She met poets and tycoons-in-waiting, dreamers and cynics; she witnessed hyperinflation and explored the nightmares of Soviet history which lie hidden under every picnic in the woods. She fell in love and carefully recorded the fears and aspirations of a generation coming of age in a country shedding its Soviet skin for a new Russian freedom.

Its hard not to read her sumptuous record now without thinking of what would come later. Were there already signs of how crooked reforms would become? How democracy would turn to what Russians call dermocracy, shitocracy? Can we already spot the coming of Putinism? Todays wars? As one is drawn into the lives of Voronezhs young, it is tempting to imagine where they are today: who has become a corrupt bureaucrat, and who is fighting in Ukraine; who has found Orthodox Fundamentalism, who is living in Kensington, and who has drunk himself to death.

Can one glimpse the future catastrophes among the parties and kisses? Is the worm which will turn and return Russia to authoritarianism already there in Hobsons funny book? And if so, where is it? In Russias denial of its own dark past? In the Wests cack-handed attempts to develop the economy? In the way Hobsons Russian boyfriend turns away from her?

But while one can read Black Earth City through a dark screen where young people enjoy themselves, unaware of impending tragedy, one can read it another way, too. The world Hobson writes about is full of ideas, daring and wit. It is open to the West, hungry for friendship, ready to welcome an Anglichanka blown in from Edinburgh. Is this warm, ebullient Russia really gone? Has it really become submerged beneath the Kremlins nausea-inducing television which sees a Western conspiracy behind everything? Its impossible to think, while reading Black Earth City, that all is lost. There is so much energy here, so little genuine enmity, so many bridges across which one could build contacts, so many different subjects to engage with and people one wants to get to know.

Black Earth City is not an overtly political book; it is a book about people living through tumultuous political times, but it becomes even more important to republish it as Russia becomes a political problem. More than just a tender portrait of the Russian people, Black Earth City also shows how one can engage with something you thought strange and dangerous yet turns out to be far closer to home than you ever imagined. It would have been easy for Hobson to make her Russian characters caricatures, bizarre foreigners. Instead she enters their minds so gracefully they become almost family: Voronezh might be just down the road.

Peter Pomerantsev, 2017

BBC Breakfast News

19 August 1991: 6 a.m.

On the screen, tanks rolled silently through a leafy boulevard in north Moscow.

Mikhail Gorbachev is no longer in charge of the Soviet Union, the newsreader was saying. It was the early-morning rush hour and yellow buses were weaving in and out, dodging the gun barrels. Commuters pressed their faces against the windows and gaped. Within the past three hours, the Soviet news agency TASS has announced that Mr Gorbachev cannot continue in office because of the state of his health. All power has been transferred to a right-wing Emergency Committee, headed by Vice-President Gennady Yanaev. Tanks have been moving towards the centre of Moscow for several hours. Russian television and radio stations are broadcasting only the Emergency Committees announcement and the camera cut, suddenly, to show the corps de ballet in Swan Lake pattering across a stage in their tutus Tchaikovsky and Chopin. This appears to be a military coup.

*

There was a time before I went to school when my mother and I visited Russia once a week. Welcome to Russia, the lady always said. It was an overheated flat just outside Southampton, full of photographs of ballet dancers. In Russias front room, where I was sent to play, two unfriendly, stiff-legged pugs lay snoring on the carpet. I didnt object, however, because of the miraculous house that sat on top of the television. It had gingerbread walls and spun sugar icicles hanging off the roof and its path was paved with chocolates and lined with jelly flowers. While my mother declined Russian nouns, I climbed up on a chair and passed the time in awed and loving contemplation of the house. She always bribed me not to touch it. A Curly Wurly on the way home if you leave the house alone. Every week the temptation was too great. A little piece of the back wall and an icicle or two would disappear, and she and the lady emerged at the end of her lesson to find sugary smears across my cheeks and a welling of guilty tears. Thus I discovered that Russia was forbidden, and that it tasted of gingerbread.

My mother never gave up her Russian lessons. Between driving four children to school, delivering stews to her parents, knitting jerseys like hairy beasts and cooking for a stream of guests, she would pull a tattered exercise book out of her handbag and memorise Russian vocabulary. Sometimes she taught me a few words: snyeg idyot its snowing sounded like little hooves. On Saturday mornings, Id climb into her bed while she did her homework. Lying in the curve of her waist and watching the strange letters flow from her green felt-tip, I pondered the information that my grandfather Igor was born in a yellow house in Moscow and bound in swaddling clothes. We had an icon from that house, a Madonna encased in silver-gilt with glass jewels in her crown, and Russian Easter eggs made of wax with velvet ribbons. All of these and my grandfather, wrapped like a swiss roll: I turned the images over in my head and grinned to myself under the bedclothes.