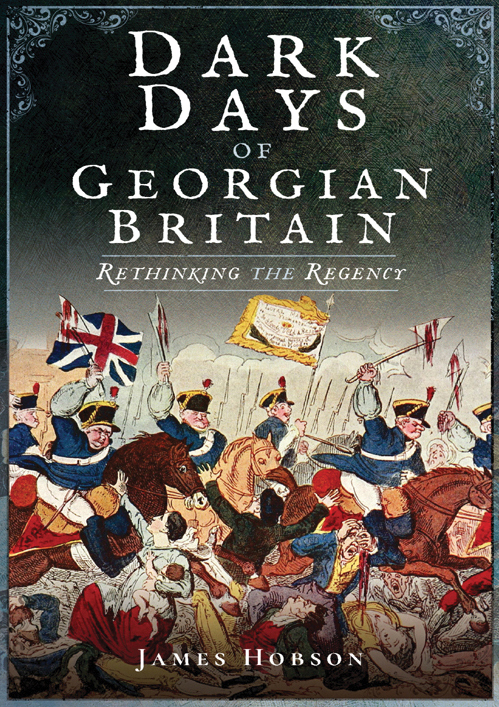

Dark Days of Georgian Britain

Dark Days of Georgian Britain

Rethinking the Regency

By

James Hobson

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright James Hobson, 2017

ISBN 978 1 52670 254 8

eISBN 978 1 52670 256 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 255 5

The right of James Hobson to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

By TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall, PL28 8RW

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For Christine, my wife.

Introduction

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her .

Jane Austen Emma (1815)

T his book is not the Anti-Austen. I am not using Emma Woodhouse as a stick to attack Jane Austen; Emma is a fictional character and it is the author who admits that she is insulated from the worst effects of these terrible years. Austen was also more than capable of making judgements about the rich and powerful and wrote about aristocrats and clerics who were neither moral, nor glamorous. This is also the basis of my argument, but my material is different war, corruption, poverty, class selfishness and political repression.

Dark Days of Georgian Britain is more of an attempt to agree with Jane, probably a wise move on my part. I accept Karl Marxs view that the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggle, and I think Jane might have at least considered the notion. Her genius would not have been enhanced with a passing reference to bread prices or trade unionism. She manages to be a moralist about society without any of this. However, some grim background might be useful, especially when the Regency is often portrayed through the TV and cinema screen as looking even lovelier than it does in prose.

The point still stands that, if you were not lucky enough to be Emma Woodhouse or one of her ilk, then this era of history was appalling in nearly every way that a period could be. This is no comment on Austen however; portraying this misery was not what she was trying to achieve, so she cannot be condemned for not achieving it. It bears repeating though: the late Regency was terrible, truly appalling, and people at the time knew it.

Indeed, when historians debate the worst year in history, the only recent year that is considered is 1816, and its earlier competitors are usually times of vicious epidemic disease or fratricidal civil war. I contend that 1800 to 1819 were the most dismal years in the last three centuries in Britain, with 1815 to 1819 being the worst. They had the full range of calamities climate crisis, war, austerity, social unrest, a rotten and corrupt system of law, welfare and government, and a ruling class too scared and arrogant to do much about it. Unlike disease and civil war, it was only the lower orders that were affected by the Regency crisis.

The rich and privileged are present in this book, but only in their role as tormentors of the ordinary people or as thoroughly bad examples. They are not presented as cardboard-cut-out villains, but I will admit to having no sympathy for them. The poor are my main interest, although they are not always presented as heroes. There was little scope for heroics when conditions were so bad.

Luckily, this is one of the first eras in history in which the voice of the poor can be heard, albeit faintly and often through the filter of people who had no regard for them. The eighteenth century was a time of rising literacy and for the first time the lower orders could sometimes speak without the squire or the vicar looking over their shoulder. We also have, faintly but with growing confidence, the voice of women. I have tried to find original stories of real people that shine a light on their life.

The book falls into four parts: the appalling experiences of the poor in the years 1811-1820; the failure of the rich to help and their tendency to make things worse; the ramshackle and the corrupt nature of the British state; and finally, some aspects of social history which show how very different we are from our Regency ancestors.

Chapter 1

The Darkness Years

This year has been a very uncommon one. The spring was exceeding cold and backward or rather there was no spring, the summer was cold and wet, or rather we had no summer. The Crop was very bad and unproductive. The Harvest was very late, the crop was not well got in. A Scarcity has taken place. The Quartern loaf is 1/6, other articles in proportion.

There never was so many beggars as thee is at present in our streets. Taxes are high and are levied with Severity. Petitions for a reform have been presented to the Prince Regent from London and other Cities, and have not been well received. Neither trade nor commerce are revived. Tradesmen and labourers are out of employ and are in a state of Starvation. The Regent and his ministers do not seem to care for the grievances under which the Nation groans under, and seem to be deaf to a reform of flagrant abuses that universally exist in the expenditure of the Public money.

Diary of Edward Lucas of Stirling, 31 December 1816.

T he title of this book is more than a metaphor. The period 1810 to 1820 was one of the darkest and coldest in the last 200 years. The causes are well known now; in April 1815 there was a colossal eruption of Mount Tambora, in present-day Indonesia. It was the biggest explosion on our planet for 80,000 years, pushing ash and pumice into the air, but more importantly, pushing sulphur above the atmospheric level of the weather. The sulphur became sulphuric acid. The earth cooled, harvests were decimated and trade and transport were hugely affected. Between 1809 and 1820 there had only been one really good harvest in Britain, that was in 1815, just before the eruption. 1816 was the worst; it was The Year Without A Summer; forty days of rain in spring in most of the country; frosts in June and July; orange and brown snow in winter; and bright yellow and reddish-brown sunsets, as clearly shown on Turners painting from this period.

The cause was not known at the time, although it was suspected by some that the weather was outside of normal variations. The Leicester Journal commented in July 1816, such inclement weather is scarcely remembered by the oldest person living.

The temporary cooling was made worse by a cyclical increase in sunspots called the Dalton minimum, which also reduced global temperatures. On some days in July 1816 the sunspots could be seen quite easily with the naked eye and some people panicked, thinking the end of the world was approaching.

Next page