www.headofzeus.com

For my brother Colonel Christopher Bates and sister Felicity Rickard

Contents

A change in life itself

ROBERT SOUTHEY

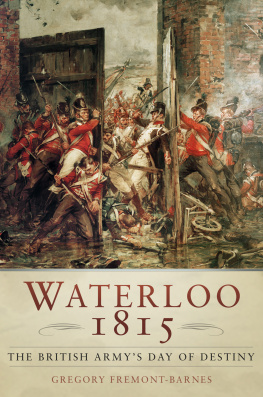

At about nine oclock in the evening on Sunday 18 June 1815, Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, commander of the British, Dutch and Belgian forces in that days battle, rode forward to meet Field Marshal Gebhard von Blcher, the Prussian general whose troops had arrived a few hours earlier, in time to drive the French army of Napoleon Bonaparte finally from the field and from waging war in Europe.

They met, surrounded by piles of dead and dying troops, the wounded and the exhausted survivors of the great, climactic conflict, as cannon smoke and the smell of gunpowder wafted acridly across the trampled, muddy, debris-strewn cornfields of the rolling farmland south of Brussels. Around them lay nearly 50,000 casualties from the 180,000 troops estimated to have taken part in the battle. There were men killed outright by musket-balls large and sluggish enough to punch huge mortal wounds in chests and stomachs and by cannon-balls which, bounding through the air and visibly bouncing off the ground like footballs, could decapitate a soldier or knock over a line of men. Those who had been wounded, if they were lucky, might survive the ministrations of sawbone surgeons and, if they were not, would die agonizingly slowly of gangrene, shock and exposure, or at the hands of the local and military scavengers who were already beginning to creep across the battlefield to see what they could pillage.

Mein lieber Kamerad! exclaimed the septuagenarian Marshal Blcher, before resorting to the one language he and Wellington had in common, that of their enemy: Quelle affaire! It was, the duke supposed unfairly the only French the old man had; but it did not stop Blcher apparently pointing to the propitious name of the farmhouse near where they were meeting: La Belle Alliance. What a name for the battle, he suggested. No, the duke thought better of the idea. In the British tradition, it would be named after the nearest small town, a couple of miles further north on the road back to Brussels: Waterloo.

It had been a battle so enormous, so terrible and so decisive that the great powers of Europe did not go to war with each other again for nearly forty years, until the Crimean War in 1854. Waterloo was also, at the time and for nearly a century afterwards, the battle of the nineteenth century as far as Britain was concerned. All its other battles were distant affairs on a much smaller scale, in the Crimea or far away on colonial frontiers. Decades later Waterloos wizened survivors would be pointed out, celebrated and eventually even photographed as veterans and heroes all, as if, like Shakespeares warriors, gentlemen in England then a-bed, or even unborn, still held their manhoods cheap they were not there. So great was the honour that some, most notably the Prince Regent, would later claim they had indeed been present at such a famous British triumph of arms. The fat, gout-ridden, rouge-smeared prince came to believe he had even led a cavalry charge. When he said so in front of Wellington, the duke replied dryly: I have heard you Sir say so before, but I did not witness this marvellous charge. Then and ever since, the fact that most of the dukes army even before the Prussians arrived were not actually British has often been forgotten, not least by Wellington himself. But what was of even greater significance for the country was that the defeat of Napoleon not only brought to an end a continental conflict that had lasted for nearly a quarter of a century, throughout the adult life of most of the troops taking part, but that it ushered in almost a century before British troops would again be engaged in Europe. Not for another ninety-nine years and sixty-six days would British soldiers open fire on a western European enemy. When they did so, on 23 August 1914, it would be thirty miles down the road from Waterloo, at Mons.

The battle of Waterloo was therefore a decisive culmination of a period in British history, but also a hinge point in it: a short, sharp break between the distant worlds of the eighteenth century and the modern, scientific, technological age, as contemporaries saw it, of the nineteenth. A single days battle (the preliminary skirmishes two days before, serious though they were, tended to be overlooked) had changed Britain irrevocably. Above all, Waterloo created a sense of national pride and a sentiment, not entirely unlike the warm glow that infuses modern memories of the Second World War 130 years later. Wellington famously described the battle as a close-run thing and so it was: it might very well have ended differently, but the victory, however achieved, helped shape the nations identity and self-esteem across the coming century.

What sort of country, though, was Britain in 1815? It was not one filled with martial ardour, not a country in which there was any sense of being all in it together. The long-running war imposed a considerable financial burden on the nation. It had cost the equivalent of six times the national income of the 1790s by the time it finished in 1815: the astonishingly precise figure cited was 1,657,854,518. The national debt almost quadrupled from 228 million to 876 million, and the interest on that debt at the end of the war was more than the entire government spending had been at its start. But the cost did not overwhelm the country and the income tax which had been introduced to fund the war was abolished in 1816. Indeed, Britain could afford to fight an entirely separate war on another continent, against the United States, at the same time that cost another 25 million a war which had ended in one of the British armys most humiliating defeats only six months before Waterloo (see Chapter 1).

The British soldiers who fought on that June day were in many ways separate from the country and the society they were defending. Britain did not use conscription for its soldiers, though it still seized and impressed sailors for its navy. It was not a peoples war, as the major conflicts of the twentieth century would be. The troops were regulars, mostly drawn from the labouring and unemployed classes, many of them from Ireland and Scotland, the majority of whom had not fought in the previous battles of the Napoleonic wars and so were raw in combat. Many of those who survived would not see their homes and families again for years and, in the days before photography and easy contact, might not be recognized when they did return. There were some who suspected it was a deliberate government policy; in the words of the short-lived radical broadsheet Black Dwarf in 1817: The army and the people are therefore separated from each other altogether and no intercourse must be allowed where it can be prevented lest the soldier should begin to remember that he is a man. Their officers were usually members of the aristocracy and gentry who had bought their commissions and were scarcely chosen for their military abilities. Quite the reverse, they were united only by the belief that their place was to command.

Yet that did not mean that the effects of the wars were not experienced indirectly by the wider population. Although Britain itself had not been invaded scattered landings in Ireland and Wales in the winter of 17967 had been easily repulsed many of the countrys young men, particularly those living near the Channel coast, had signed up for local militia units. These tended to be derided by cartoonists as full of gormless toy soldiers in ill-fitting fancy uniforms, bumpkins employable only to defend their local districts. But many had been tradesmen or were from the professional classes 40 per cent of Edinburghs volunteers were lawyers in 1797: men with something to lose, defending home and hearth, recruited earlier in the war when there was a real fear of a French invasion. Their presence, drilling and parading, formed a constant background to country life and, in the absence of a regular police force, they would be called in to keep order and put down disturbances such as those that sprang up in the years after 1815. As the war ended, there were perhaps 600,000 men in uniform in the army and navy: a huge number in a country of maybe 13 million people. By 1815 the country was having difficulties recruiting enough men of the right age and aptitude for soldiering.

Next page