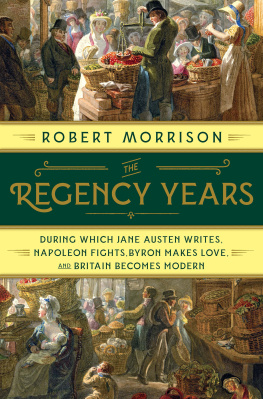

THE

REGENCY YEARS

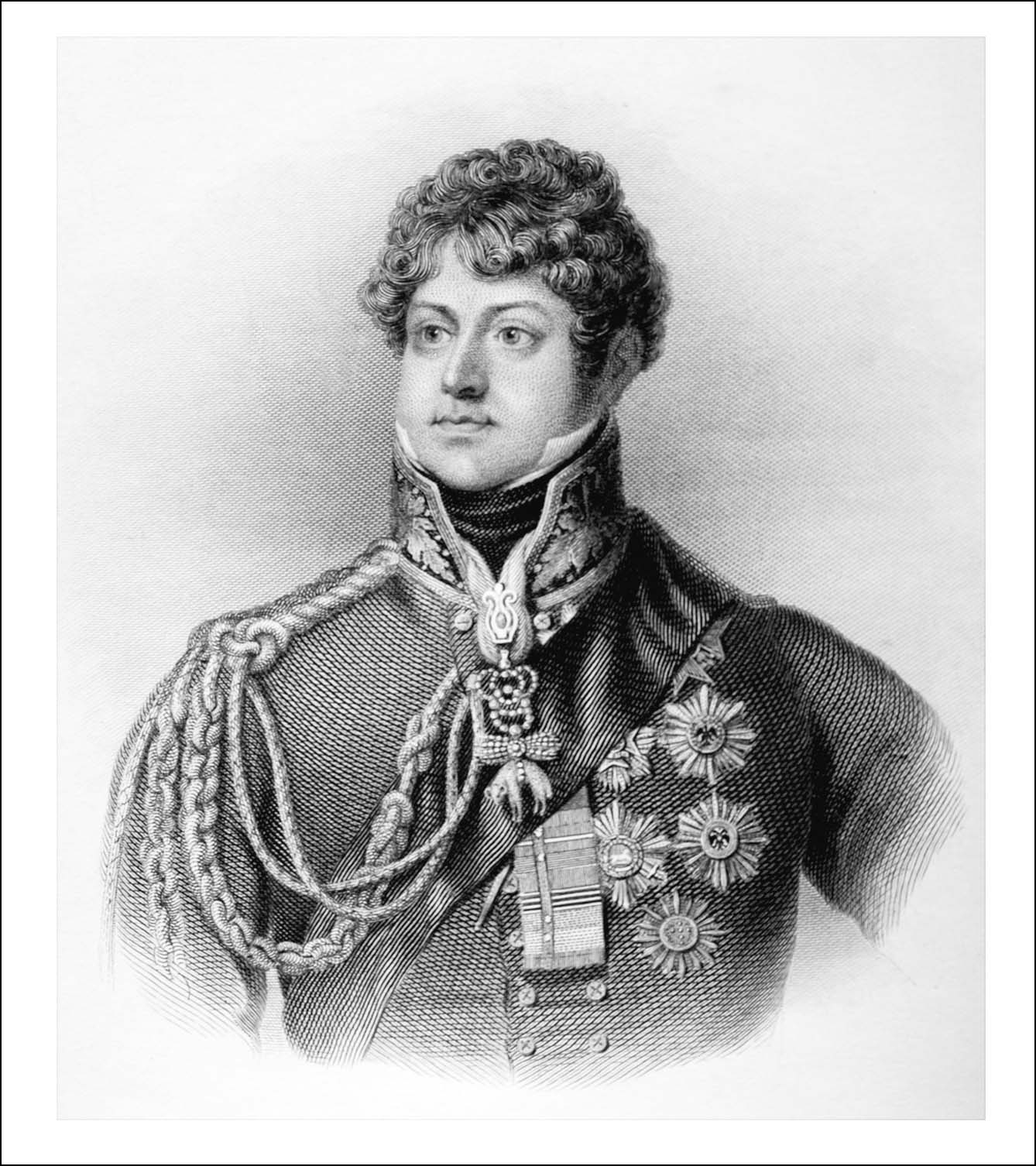

The Prince Regent, engraved by A. Heath

THE

REGENCY

YEARS

During Which Jane Austen Writes,

Napoleon Fights, Byron Makes Love,

and Britain Becomes Modern

ROBERT MORRISON

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923 / NEW YORK LONDON

For Carole

Again and Always

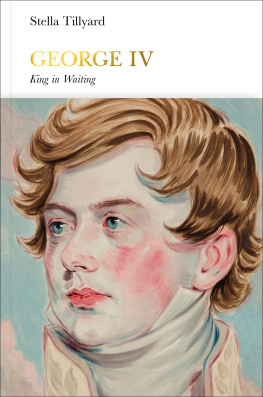

The Regency began on February 5, 1811. King George III had been crowned in 1760, and had presided over both the loss of the American colonies and Britains struggles against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. But he was replaced as Britains ruler because he suffered from some form of insanity, which struck him down several times during his long reign, and which in late 1810 cast him into darkness, clearing the way for the Regency of his dissolute eldest son, George, Prince of Wales, who ruled Britain as Prince Regent until January 29, 1820, when George III died and the Regent became King George IV. Despite its brevity, the Regency was a time of major events, from the Luddite Riots and the War of 1812 to the Battle of Waterloo, the explosion of Mount Tambora, and the Peterloo Massacre. And it had a glorious cast, including Jane Austen, Beau Brummell, Lord Byron, John Constable, John Keats, Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, J. M. W. Turner, the Duke of Wellington, and of course the Regent himself. But there were dozens of other figures who made a decisive contribution to the period, including athletes (Tom Cribb), artists (Mary Linwood and Thomas Rowlandson), engineers (Thomas Telford), explorers (John Franklin), inventors (Charles Babbage), journalists (Pierce Egan), novelists (Mary Brunton and Maria Edgeworth), poets (John Clare), reformers (Elizabeth Fry and Robert Owen), and scientists (Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday). While I recognize the deep continuities between the Regency and the decades that both preceded and followed it, I believe the Regency is perhaps the most extraordinary decade in all of British history. It is certainly the period that most definitively marks the appearance of the modern world.

In fiction, the Regency is brought most vividly to life in William Makepeace Thackerays magnificent Vanity Fair (184748) and in the novels of Georgette Heyer, including Regency Buck (1935) and An Infamous Army (1937). Popular studies began with William Cobbetts History of the Regency and Reign of King George the Fourth (183034), continued through a number of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century accounts, and culminated in the 1970s and 1980s in a spate of shorter surveys, including those by Joanna Richardson, Donald Low, and Carolly Erickson. There have been a host of books on individual aspects of the Regency, including its architecture, art, fashion, furniture, politics, prizefighters, and rakes. There have also been a number of studies that fold the Regency into a longer historical survey, including Paul Johnsons magisterial The Birth of the Modern (1991), or that see it variously as a part of the Age of Atonement, the Age of Elegance, the Age of Improvement, the Age of Revolution, or the Age of Wonder. Several studies, too, have been devoted to an examination of the Regency world of individual authors, including, most prominently, Austen and Byron.

Yet despite the wealth of interest, this book is the first in more than three decades to focus solely on the Regency years, and in its account of the periods remarkable diversity, upheaval, and elegance, it pushes well beyond the scope of any previous work on the decade. It builds on the key sources about the Regency, including the memoirs and journals of Frances Burney, Joseph Farington, Rees Howell Gronow, and Henry Crabb Robinson. More importantly, it taps the rich stores found in recent biographies of leading figures, including Percy Shelley and the Duke of Wellington, as well as in new editions of works by Regency authors, from well-known writers like Jane Austen to lesser-known figures such as the courtesan Harriette Wilson and the diarist Anne Lister, who during the Regency recorded in code her joyous experiences of same-sex love.

Above all, this book ranges across the decade to mark the moment when Thackeray and Charles Dickens were boys, Benjamin Disraeli and Thomas Macaulay were teenagers, and John Keats and Thomas Carlyle (both born in 1795) were young men. It considers Britain at home and abroad, at war and at peace, at work and at pleasure. It brings the central figures of the period into dialogue with one another, as Turner chats with Constable, Lady Caroline Lamb pursues Byron, Wellington spies Napoleon across the battlefield, Keats watches Edmund Kean on stage, and Mary Russell Mitford enthuses over a lecture by William Hazlitt. In its dreams of equality and freedom, its embrace of consumerism and celebrity culture, its mass radical protests in support of parliamentary reform, and its complicated response to the burgeoning pace of industrial, technological, and scientific advance, the Regency signals both a decisive break from the past and the onset of the desiring, democratic, secular, opportunistic society that is for the first time recognizably our own.

The Regent and the Regency

In Ireland there were government crackdowns and bitter outbreaks of sectarian violence; in Scotland landlords were clearing their estates for sheep farming by forcing thousands of Highlanders from their homes; and in England there were riots in the industrial Midlands and widespread despair in the agricultural districts. And this was to say nothing of the monumental struggle Britain was waging in Europe against Napoleonic France, or the anger building between America and Britain that led less than a month later to the two countries descending into the War of 1812.

Long before Moira finished, the Regent was very nearly in convulsions, and Moira suggested that he return the next day in order to allow the Regent time to compose himself.these meetings caused him, and the turmoil that continued to sweep through the country, the Regent rarely took more than a sporadic interest in domestic politics. The result was repeated and often ferocious attacks on him by satirists, caricaturists, political enemies, and discarded friends, all of which created an image of him as self-indulgent, incompetent, and lachrymose that has endured from his day to ours.

Nonetheless, if widely despised and too often oblivious in matters of state, the Regent in matters of taste and style left a profound impact on his era, for in his love of both elegance and excess, violence and restraint, learning and lasciviousness, the low-brow and the high-minded, he embodied many of the extremes that have come to define his Regency, not only within court circles but also much further down the social hierarchies. His love of prizefighting, horse racing, and the theater set the tone for the age, as did his delight in consumerism. Gamblers bet wildly, like him, on cards and dice, losing far more than they could afford and racking up cripplingly high debt loads. The Regents vast consumption of food and especially drink empowered male and female debauchees from across the social spectrum. His days and nights of committed libertinism inspired rakes of both sexes, who throughout his Regency enjoyed an unabashed revelry of promiscuity and pornographic obsession.

Next page