ELEANOR GORDON-SMITH is a philosopher, radio producer and recovering debater working at the intersection of academic ethics and the chaos of ordinary life. Currently at Princeton University, she has contributed to This American Life, The Australian, the Sydney Morning Herald, Meanjin, The Ethics Centre and ABC Radio Nationals The Philosophers Zone.

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Eleanor Gordon-Smith 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

ISBN: 9781742235875 (paperback)

9781742244389 (ebook)

9781742248905 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

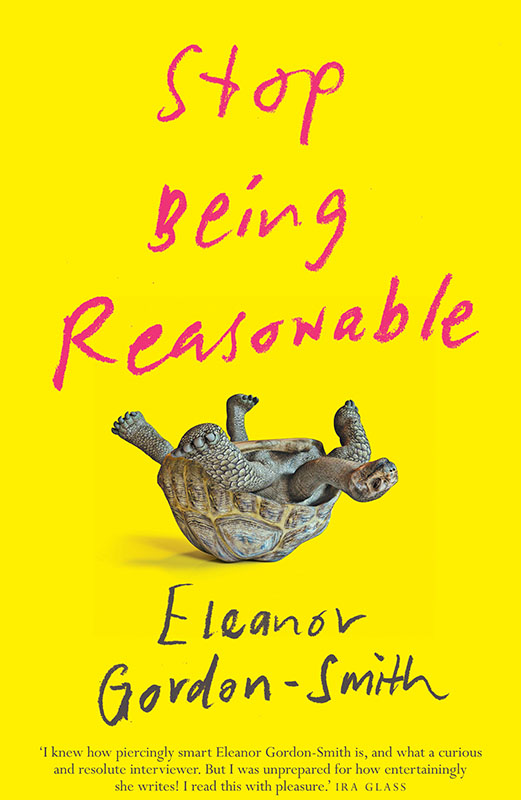

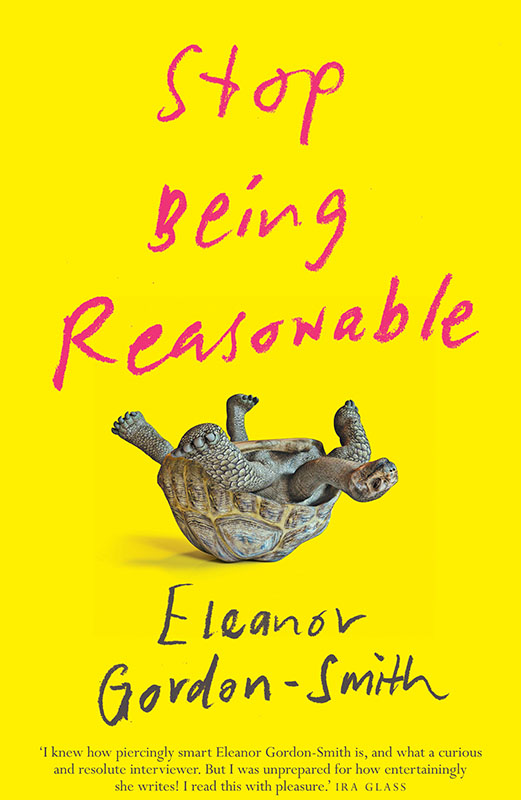

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Design by Commitee

Cover image Digital Storm, Bigstock

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Contents

To Claire, Michael, Marie, Jackie, Brush, and their grace when I was sixteen and always right.

Chapters 4 and 5 contain material that readers may find confronting or disturbing.

Everything was protein powder and nothing hurt

S OMEWHERE IN THE TECHNOLOGICAL BELT OF California, where the only thing more precisely engineered than the software is the people or maybe the peoples teeth lives an organisation called the Center for Applied Rationality. For the low price of US$3900 the Center will sell you a four-day workshop on reasoning during which participants eat, sleep, and do nine hours of back-to-back activities together daily under one (presumably rationally designed) roof. This year, just like every other year, the Center will receive hundreds of applications from people who want to attend because, as they put it, Everyone I know is irrational, and I want to fix them.

Easy punchline. Good group to laugh at. But it turns out many of us make a version of the same mistake when we think about persuasion. We think we know what it is to change our minds rationally, and the only question is why other people dont do it more often. The ideal mind-change is calm. It reacts to reasoned argument. It responds to facts, not to our sense of self or the people around us. It resists the siren song of emotion. People like to talk about the public sphere if there is such a thing then its convex edge reflects this idealised image back at us. Think of the number of programs dedicated to the mind-changing magic of two sides saying opposite things. Topical Debate, promises the BBCs Question Time. Big Ideas, offers the ABC. Adventures in democracy, proclaims the Q&A program. The branding of these things even bakes in a little reward: how brave I am, for attending the Festival of Dangerous Ideas; how clever, for my sub-scription to the Intelligence Squared debates. The proper way to reason, at least according to our present ideal, is to discard ego and emotion and step into a kind of disinfected argumentative operating theatre where the sealed air-conditioning vents stop any everyday fluff floating down and infecting the sterilised truth.

Years ago I used to share this view. Ill tell you why, even though it will rightly make you want to take my lunch money: when I was at school I was a champion debater, which is another way of saying I spent my weekends wearing a blazer and telling people in precisely timed intervals exactly how wrong they were. My teammates and I constructed arguments for twenty hours a week, putting premises in the crosshairs with the unblinking accuracy of people whose whole egos were on the line. We werent bad, either. Eventually we made it to the world championships in Qatar where we wore blazers embroidered with the Australian coat of arms in gold and competed in what looked, in hindsight, like a scene in an apocalypse movie just before the purge begins: all of us in matching uniforms on fleets of white buses being shepherded through the desert haze to auditoriums where we would sit locked up together for an hour surrounded by stopwatch-wielding officials. Debating left me with an attitude to persuasion that was as precise as Euclidean geometry: find the foundation, show why its wrong. Buttress analysis with evidence. Emotion is for decorative flourishes only do not expect it to be load-bearing. Of course I knew you could change minds by appealing to things like emotion or your opponents sense of self, but doing that seemed kind of base. It felt nobly sportsmanlike to arm yourself with argument alone. It was the intellectual equivalent of turning up at dawn for your duel: it was how you were meant to fight.

I began changing my mind about this picture after I made a piece for US radio program This American Life in 2016. The project had seemed simple: turn around to my own catcallers men who had wolf-whistled or made sexual comments on the street and try to reason them out of doing it again. I spent hours giving these men all the evidence, all the reasoning, all the fancy footwork with premises. But in dozens of conversations I walked away defeated. Over and over again they walked away from our conversations as sure as theyd ever been that it was okay to grab, yell at or follow women on the street.

These men didnt seem fundamentally irrational, or unstuck from reality in a funny sort of way I quite liked a few of them. One told me he modelled his courtship rituals on the animal kingdom: Im just another paradise bird, flaunting my shit, he said triumphantly, as though this explained everything that needed to be explained. Thats a good line. He made me laugh. But I couldnt change their minds. The experience deflated me not just as a person and as a woman but as someone who had always been optimistic about our ability to talk each other into better beliefs. We finished recording in November 2016, right after the US general election, and it was not a good moment to be suddenly pessimistic about rational debate and persuasion.

But when the piece aired, a strange thing happened. I was inundated with interview requests. Could I write a ten-step guide to changing minds? Would I accept an award for the successful use of rational persuasion in public? What advice did I have for talking people out of workplace harassment? I was astonished. Large numbers of people had apparently listened to the conversations that I had walked away from feeling dejected and defeated, and heard instead instances of persuasive success. I think the explanation is that these conversations bore a sort of waxwork-like resemblance to what we think good mind-changes look like. I said one thing, my catcallers said the opposite thing, and each of us tried to explain why we were right. I had stayed calm, they had been prepared to hear me out. I had used statistics. It looked for all the world like a rational debate, and the fact that I had failed to achieve anything with this approach to changing minds disappeared under the shadow of the unquestioned assumption that I deserved congratulations for even trying. I started to smell a rat a big one that lives in the sewers and never takes a shower.

Next page