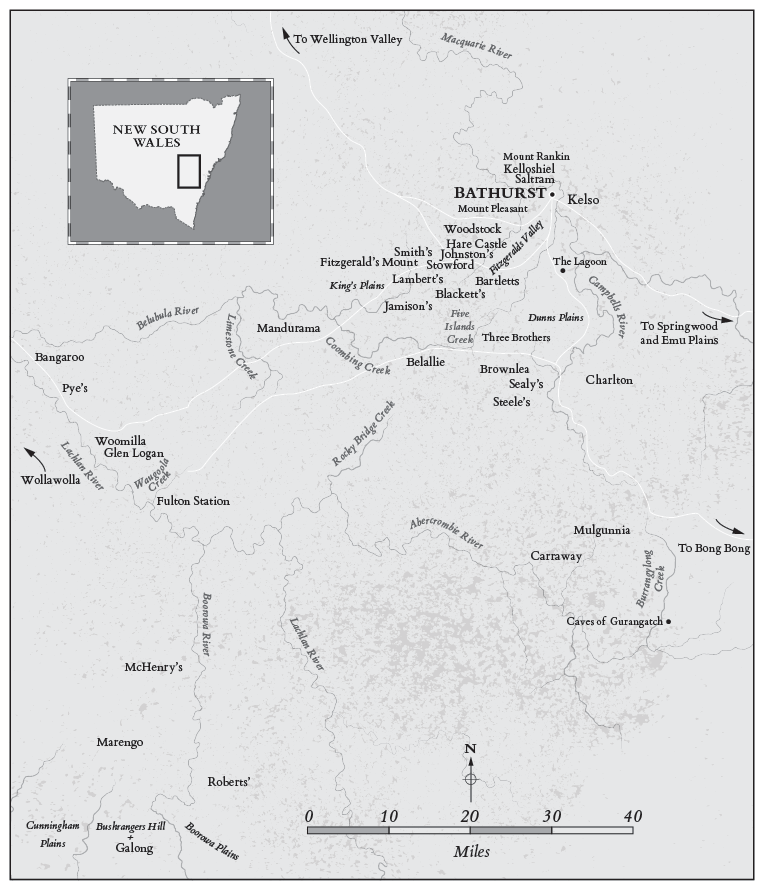

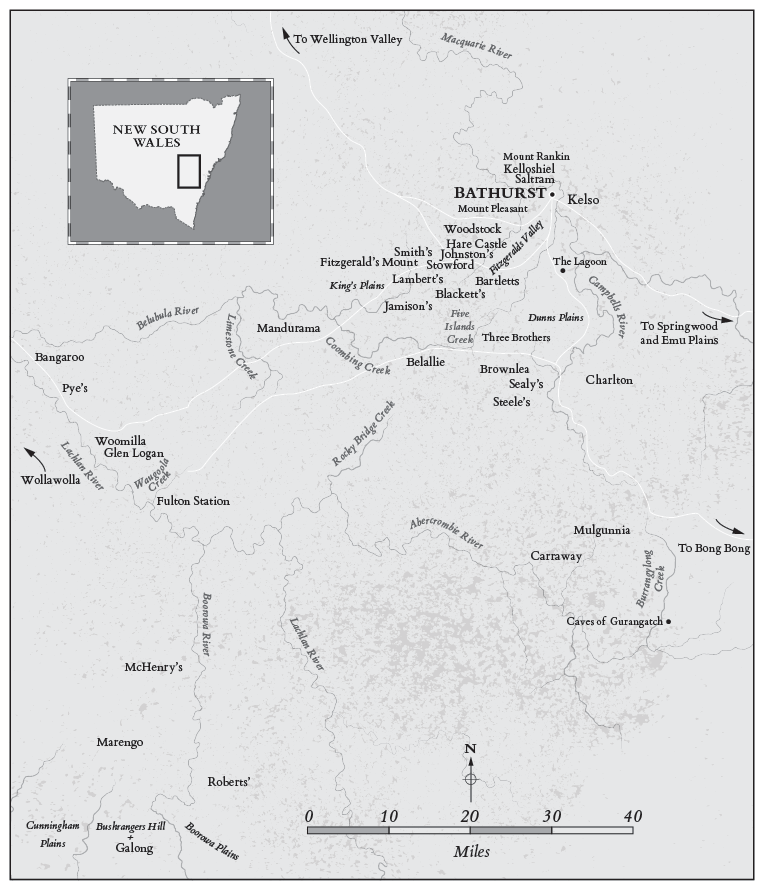

The key locations of the Ribbon Boys insurrection

For Anthony Peter Thompson

All of true blood, bone and beauty were doomed to Port McQuarie, Toweringabbie, and Norfolk Island and Emu Plain. And in those places of tyranny and condemnation, many a blooming Irishman rather than subdue to the Saxon yoke were flogged to death and bravely died in servile chains, but true to the Shamrock and a credit to Paddys land.

Ned Kellys Jerilderie letter, 1879

The wages of rebellion

Gaol, Bathurst Settlement, Monday 18 October 1830

Captain Horatio Walpole and his detachment of the 39th Regiment arrive from the Lachlan River with seven wounded captives; three others have been sent to Bong Bong. The foot soldiers executed a forced march from Sydney to Bathurst, where they were joined by a cavalcade of veteran soldiers, volunteer settlers and mounted police. Walpole has quelled the most wide-spread convict insurrection since the Castle Hill rebellion of 1804. After six days on the road, the wagon still leaks blood.

Incited by the death of the Irish folk hero Jack Donohoe, the rebels liberated eighty government servants from their Bathurst farms. They amassed enough arms, cattle and farming supplies to establish a hidden camp beyond the limits of the colony.

Ralph Entwistle looks out at the faces swarming like flies around the wounded. He sees Patrick Sullivan standing on the street gawping at his bleeding brethren. Martin Grady, riding close to Captain Walpole for protection, is unable to meet Ralphs eyes. The Boys have been brought in, the infamous Ribbon Boys, and their wounds become them.

Ralph lifts his damaged body onto one buttock against the splintered wood. He cannot find the face of George Mole. He asks Robert Webster if he has seen the boy. Webster shakes his head and throws Ralph a look of caution. They are within earshot of Lieutenant Thomas Evernden, superintendent of the mounted police.

Those still able to walk Robert Webster, John Kenny, James Driver and Dominic Daley are herded off to the cells by Constable James Parker, an Irish lifer on his Ticket of Leave. Patrick Gleeson helps the wounded William Gahan hobble alongside the constable. They start giving him the patter in the hope he will go on one side for them or at least go light.

Now, why are the government servants calling you the Ribbon Boys? Parker asks.

Gahan whispers, You have heard of the secret society sworn to punish all bad masters? Men who do dark deeds like arson and murder to avenge the Irish?

Constable Parker cranes forward to trade in secrets. Yes, the Ribbonmen?

They say we are like them, but younger and more handsome. Gahan smiles with his crooked yellow teeth.

Gleeson laughs at this.

The men ask Parker about the fate of their wounded comrades Michael Kearney, Tom Dunne and John Sheppard. They were the first rebels captured by Lieutenant Macalister, who escorted them to the hospital in Argyle County. Parker has no news of their condition.

The Protestants, Driver and Webster, are thrown into the general lock-up. Ralph is carried on a pallet to a solitary cell. This separation from the Boys is his first punishment. Lieutenant Evernden regards him as the leader of the insurrection.

The first time Ralph Entwistle was incarcerated was in a cramped dungeon cell where he breathed in the foetid air of a dozen Lancashire men sweating fear. Here, his pallet rests upon a trundle bed on a dirt floor that has been swept clean with a branch of eucalyptus; the scent lingers. In New South Wales, prison walls are made of red bricks instead of ancient stones.

The iron door clangs as Constable Shaw Strange pulls the bolt and cracks it open. He slides a bowl of gruel into the cell, and secures the door again.

Ralph reaches over to grasp the bowl then hurls it against the wall. The peephole opens at the clatter and the constable surveys the mess.

Here is the temper that stole your liberty. He clucks. Others starve so that you may eat.

The magistrates eat while the convicts starve, Ralph replies.

Ralphs body seems grotesque in this narrow room. A British bulldog by width and strength, grief has bowed his wide shoulders. He sits up, looking at his chafed ankles in their iron cuffs. He considers his injured leg. He cannot turn back the torn leg of his trousers; it has stuck to the crusted blood. His head pounds in time with his heart.

Ralph had not expected to live so long. He is twenty-six, only a year older than his mother was when she died. He unwinds her kerchief from his neck and, with his stumpy fingers, worries away at the satin threads. The letters E. Lee have almost been picked clean.

The origin of rebellion

King Street, Bolton, Lancashire, Sunday 30 June 1811

Ralph was seven when his mother died. He remembers the muffled sound of a lullaby hummed through her breast and the crackle in her voice and the death rattle. She was laid out upon a table in the front room of their cottage, stiff as a sparrow after an early frost.

In the front window sat his grandfathers loom. Ellen Lee had taken over the weaving when the old man died. She could make just enough money to feed them both. Ellen taught Ralph his letters so that he could read to her from the bible as she worked. She died from asthma. The doctor said the disease came from kissing the cotton thread through the shuttle.

On the day of the funeral, Ralph nestled under the old timber frame and would not come out. He could smell the waxiness of wear upon it, remember her clogs gliding across the floorboards, feel the sway of her body working the rhythm of the warp and woof as she sent the shuttle flying. The ribbons of cotton would sing amid the clatter and clack. He thought, I will sit at this loom until I die too .

I suppose the old thing must go now, said his Aunt Annie to the minister.

There is no market for hand looms these days, he replied.

Were it not the Reverend Cartwright invented the power looms and put good folk out of work so their families might starve? asked Aunt Annie.

I shall not take the loom, but I will have the cloth and the boy for the orphanage.

That you will not, said Aunt Annie. His father is alive and has work for him in the timber yard.

Relatives scuttered like clouds across Ralphs vision that morning his four older half-brothers, his aunt and uncle, two married half-sisters, and finally his sobbing father. Ralph did not recognise him until he was told to kiss him.

The minister led the procession down the lane and the neighbours shed tears as rare as chickens teeth over the poor little boy following along behind. The family reached the stony churchyard. After prayers at the graveside, the men took up the ropes and lowered the coffin down into a narrow pit. The minister picked up a clod of earth and threw it upon the lid of the coffin.

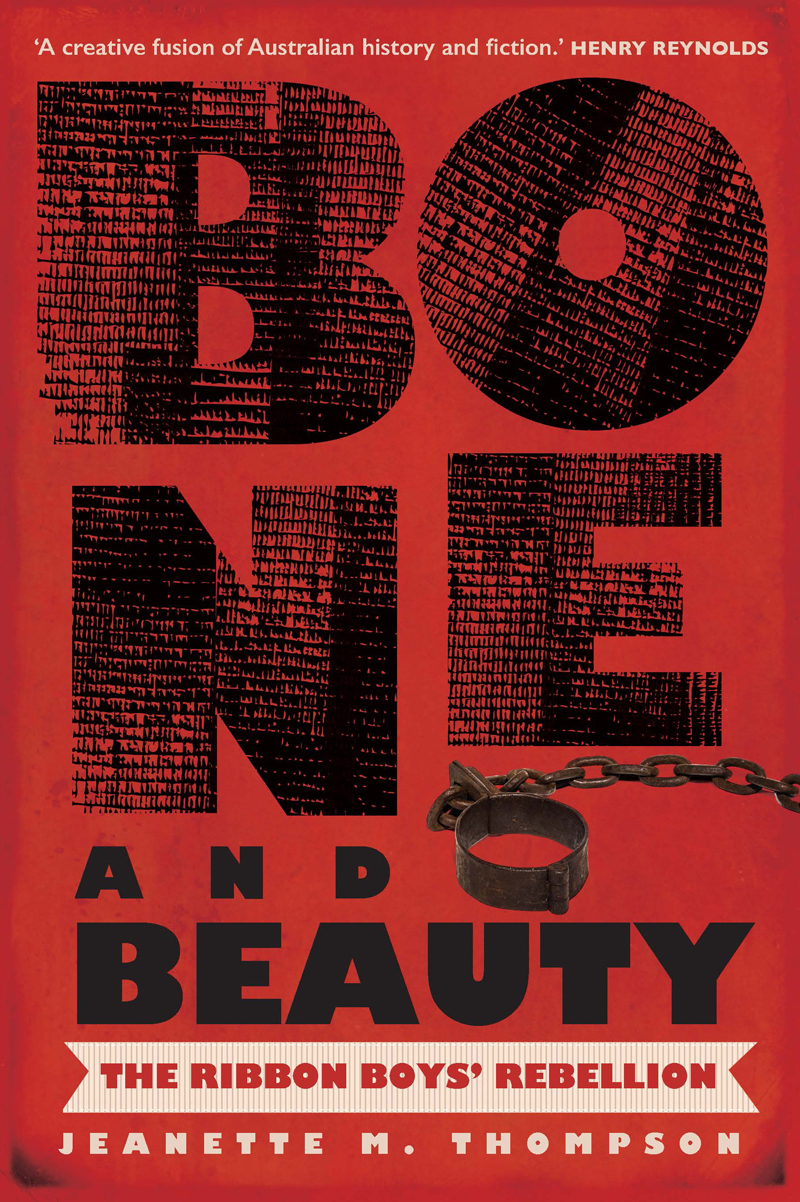

Jeanette M. Thompson graduated as Doctor of Creative Arts from the University of Technology Sydney. Bone and Beauty grew out of Jeanettes research into Australian colonial history and creative nonfiction writing. She has been a lecturer in childrens literature, Charles Sturt University, and a tutor for the Family History Unit, University of Tasmania. Her research and community writing have explored ways of making history accessible and engaging for a wide variety of audiences.

Jeanette M. Thompson graduated as Doctor of Creative Arts from the University of Technology Sydney. Bone and Beauty grew out of Jeanettes research into Australian colonial history and creative nonfiction writing. She has been a lecturer in childrens literature, Charles Sturt University, and a tutor for the Family History Unit, University of Tasmania. Her research and community writing have explored ways of making history accessible and engaging for a wide variety of audiences.