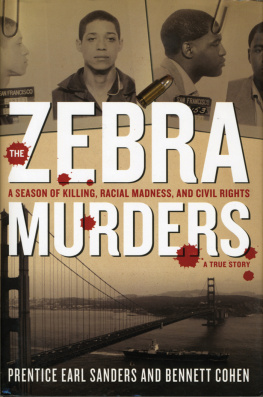

THE

ZEBRA

MURDERS

THE

ZEBRA

MURDERS

A SEASON OF KILLING, RACIAL MADNESS, AND CIVIL RIGHTS

PRENTICE EARL SANDERS

BENNETT COHEN

ARCADE PUBLISHING

NEW YORK

Copyright 2006, 2011 by Prentice Earl Sanders and Bennett Cohen

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sanders, Prentice Earl.

The zebra murders : a season of killing, racial madness, and civil rights / Prentice Earl Sanders and Bennett Cohen.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61145-043-9 (alk. paper)

1. Sanders, Prentice Earl. 2. San Francisco (Calif.). Police Dept--Biography. 3. Serial murder investigation--California--San Francisco--Case studies. 4. Serial murders--California--San Francisco. 5. Hate crimes--California--San Francisco. 6. Whites--Violence against--California--San Francisco. 7. African American detectives--California--San Francisco--Biography. 8. Discrimination in law enforcement--California--San Francisco. 9. Racism--California-San Francisco. 10. San Francisco (Calif.)--Race relations. I. Cohen, Bennett. II. Title.

HV8079.H6S36 2011

364.15232092--dc22

2011004529

Printed in the United States of America

To my wife, Espanola, my daughter, Marguerite, and my son, Marcus: You have given me the strength, courage, and inspiration to meet the challenges of life every day. Thank you for your unconditional love.

And to the memory of Rotea Gilford

Contents

Prologue

IN 1969 PETE TOWNSHEND of the Who produced the only album by a little-known band called Thunderclap Newman, with a song that became the groups sole hit: Something in the Air. The song reached number one on the British charts and thirty-seven in America. While it may not have topped the charts in the States, the lyrics, which declared that the revolution had arrived and spoke of calling out the fomenters and handing out guns and ammo, perfectly captured the hunger for change that had become like a religion for American youth, and the growing romanticization of violence as a means to that change. The song became a fixture in popular culture and was subsequently included in the sound tracks of numerous films that wanted to capture the spirit of the era, from Easy Rider to The Strawberry Statement and The Magic Christian.

The rhythms on the ghetto streets of the Fillmore and Hunters Point in San Francisco and of West Oakland across the bay during the fall, winter, and spring of 1973 to 1974 were more akin to the funky pulse of Sly Stone, Tower of Power, and the Pointer Sisters than the feathery strains of Thunderclap Newman and Something in the Air. Yet the sentiment was the same, driven by the passing of the promise felt during the 1960s and the desire, as Malcolm X put it, to change the system by any means necessary.

This was a time when the entire world seemed caught up in a confusing maelstrom of political chaos, bloodshed, and violence. Native Americans clashed with the FBI at Wounded Knee. Chile fell to Pinochets fascist junta. The Yom Kippur War raged in the Middle East. Arab terrorists fired on the Athens airport, hijacked planes, took over a train in Austria, and killed schoolchildren in the Israeli town of Maalot. The IRA, Basque separatists, and the Red Army Faction took on the institutions of Europe while the Weather Underground, SLA, and Black Liberation Army did the same in the States. It was a time when even the president, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, had to stand naked as the scandal of Watergate swirled around him and his administration crumbled at his feet. Yet for all the mayhem plaguing the globe, nowhere seemed to be more at the center of the storm than the seven miles square that form the city of San Francisco.

For six months from October 1973 to April 1974, a string of killings that came to be known by the code name Zebra afflicted San Francisco like a curse. Though little remembered or talked about today, the Zebra murders were among the most violent and prolonged cases of domestic terrorism in the history of the United States. This was not a single catastrophic event. Rather, it was an ongoing wave of random terrorist attacks that ultimately numbered nearly two dozen in total and left fifteen dead, eight injured, a population shaken, and a major U.S. city on the brink. It was a time, sad to say, that in many ways presaged our own.

In the wake of 9/11, people in their effort to come to terms with the catastrophe reached for various parallels: Pearl Harbor, the Cuban missile crisis, the assassination of JFK. What sprang to my mind was the flood of terror that washed over San Francisco nearly thirty years earlier.

I was in the Bay Area during the Zebra murders, so I thought I knew a bit about them. By my recollection, a small, radical fringe group inside the San Francisco temple of the Nation of Islam, an organization far removed from the Nation of Islam that exists today, committed a series of attacks in what I understood to be an attempt to alienate whites from blacks and instigate a race war. As I looked further into the Zebra murders, however, I realized that all I really knew was the surface of the story, and that a deeper truth lay beyond the public face. Besides terrorism, the issue at the center of this story was racism, and two very different ways of reacting to it: you can lash out and become part of the madness, or you can struggle to keep your balance and find a purposeful, nonviolent way to fight for change.

I knew the killers chose to do the former. What I didnt know was the story of two other men who were black and similarly outraged by racism, who chose to do the latter. And who chose the course of justice over vengeance while pursuing the very culprits behind the Zebra murders. I didnt know about these men, Earl Sanders and Rotea Gilford, who were the first African American inspectors of Homicide in the history of the San Francisco Police Department, because their story had gone untold for thirty years.

What led me to them was a simple sense of disbelief. I had assumed that the San Francisco of 1973 must have had numerous black officers, and I couldnt imagine that murders committed by an insular group of African Americans such as the then Nation of Islam could be solved without black policemen being deeply involved. Yet thats exactly what the reports I read implied, with every black officer mentioned always relegated to the periphery of the action rather than positioned at the heart of it.

I decided to dig deeper. An Internet search brought up a San Francisco Chronicle article from 1995 about an African-American SFPD Homicide inspector named Earl Sanders being promoted to lieutenant, who listed the Zebra murders as one of his more famous cases. More searching revealed that Sanders had since been made an assistant chief, second-in-command of the department, and the highest-ranking black officer in the department ever. So, with little expectation of an answer any time soon, I called his office and left a message, saying I was a writer in Los Angeles and wanted to talk to him about a case called Zebra.