Contents

Guide

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2020 by Louisa E. Miller

Illustrations by Kate Samworth

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition April 2020

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Carly Loman

Jacket design by Alison Forner

Jacket illustration by Kate Samworth

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-1-5011-6027-1

ISBN 978-1-5011-6037-0 (ebook)

This is for you, Dad.

Prologue

P icture the person you love the most. Picture them sitting on the couch, eating cereal, ranting about something totally charming, like how it bothers them when people sign their emails with a single initial instead of taking those four extra keystrokes to just finish the job

Chaos will get them.

Chaos will crack them from the outsidewith a falling branch, a speeding car, a bulletor unravel them from the inside, with the mutiny of their very own cells. Chaos will rot your plants and kill your dog and rust your bike. It will decay your most precious memories, topple your favorite cities, wreck any sanctuary you can ever build.

Its not if, its when. Chaos is the only sure thing in this world. The master that rules us all. My scientist father taught me early that there is no escaping the Second Law of Thermodynamics: entropy is only growing; it can never be diminished, no matter what we do.

A smart human accepts this truth. A smart human does not try to fight it.

But one spring day in 1906, a tall American man with a walrus mustache dared to challenge our master.

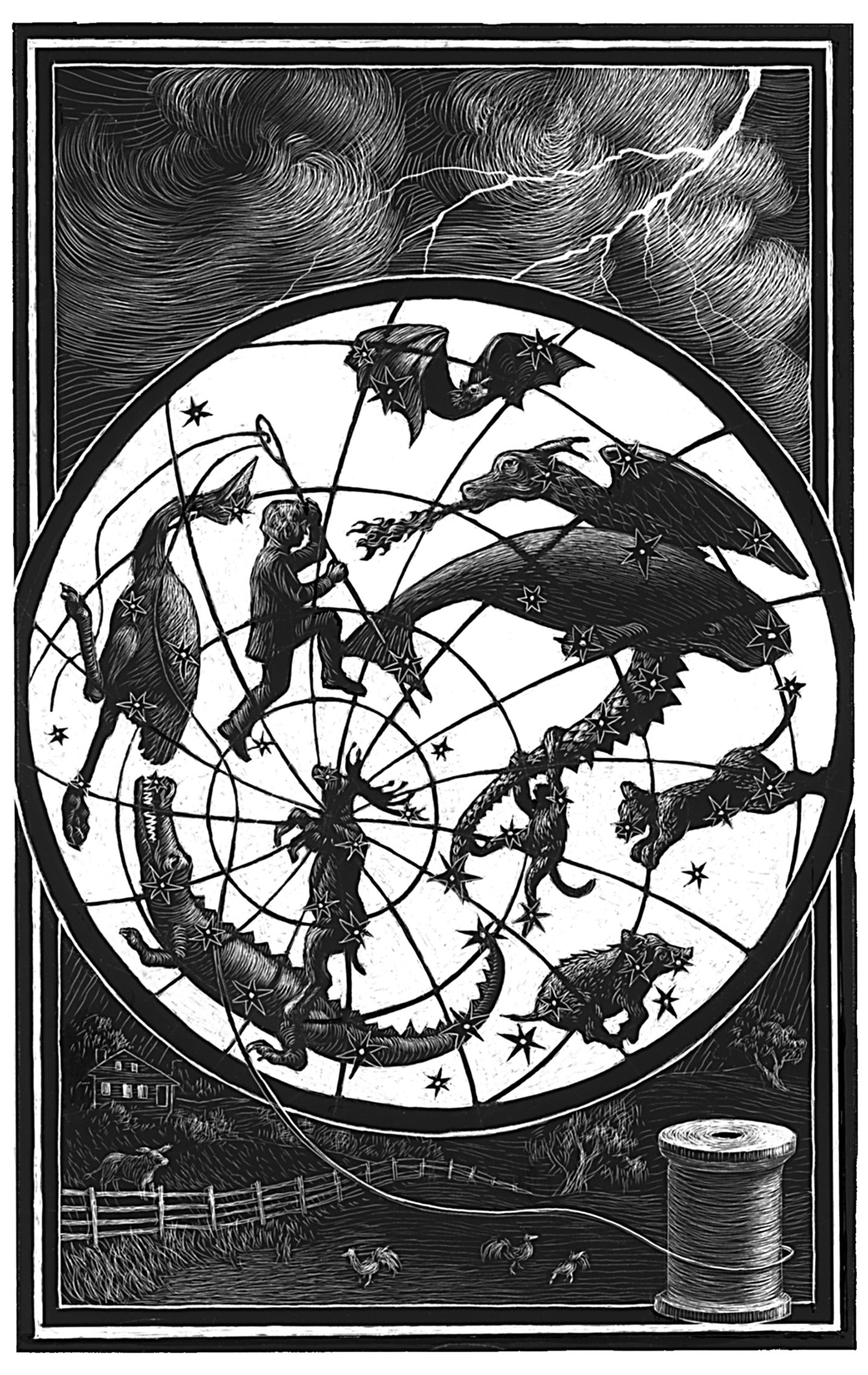

His name was David Starr Jordan, and in many ways, it was his day job to fight Chaos. He was a taxonomist, the kind of scientist charged with bringing order to the Chaos of the earth by uncovering the shape of the great tree of lifethat branching map said to reveal how all plants and animals are interconnected. His specialty was fish, and he spent his days sailing the globe in search of new species. New clues that he hoped would reveal more about natures hidden blueprint.

For years he worked, for decades, so tirelessly that he and his crew would eventually discover a full fifth of fish known to man in his day. By the thousand he reeled in new species, dreaming up names for them, punching those names into shiny tin tags, dropping the tags alongside their specimens into jars of ethanol, slowly stacking his discoveries higher and higher.

Until one spring morning in 1906, an earthquake struck and toppled his shimmering collection to the ground.

Hundreds of jars shattered against the floor. His fish specimens were mutilated by broken glass and fallen shelves. But worst of all were the names. Those carefully placed tin tags had been launched at random all over the ground. In some terrible act of Genesis in reverse, his thousands of meticulously named fish had transformed back into a heaping mass of the unknown.

But as he stood there in the wreckage, his lifes work eviscerated at his feet, this mustachioed scientist did something strange. He didnt give up or despair. He did not heed what seemed to be the clear message of the quake: that in a world ruled by Chaos, any attempts at order are doomed to fail eventually. Instead, he rolled up his sleeves and scrambled around until he found, of all the weapons in the world, a sewing needle.

He took the needle between his thumb and forefinger, laced it with thread, and aimed it at one of the few fish he recognized amid the destruction. With one fluid movement, he plunged the needle through the flesh at the fishs throat. Then he used the trailing thread to stitch a name tag directly to the flesh itself.

For each fish he could salvage, he repeated this tiny gesture. No longer would he let the tin tags sit precariously in the jars. Instead, he sewed each name directly to the creatures skin. A name stitched to its throat. To its tail. To its eyeball. It was a small innovation with a defiant wish, that his work would now be protected against the onslaughts of Chaos, that his order would stand tall next time she struck.

When I first heard about David Starr Jordans attack on Chaos, I was in my early twenties, starting out as a science reporter. Instantly, I assumed he was a fool. The needle might work against a quake, but what about fire or flood or rust or any of the trillion modes of destruction he hadnt thought to consider? His innovation with the sewing needle seemed so flimsy, so shortsighted, so magnificently unaware of the forces that ruled him. He seemed to me a lesson in hubris. An Icarus of the fish collection.

But as I grew older, as Chaos had her way with me, as I made a wreck of my own life and began to try to piece it back together, I started to wonder about this taxonomist. Maybe he had figured something outabout persistence, or purpose, or how to go onthat I needed to know. Maybe it was okay to have some outsized faith in yourself. Maybe plunging along in complete denial of your doomed chances was not the mark of a fool butit felt sinful to think ita victor?

So, one wintry afternoon when I was feeling particularly hopeless, I typed the name David Starr Jordan into Google and was met with a sepia photograph of an old white man with a bushy walrus mustache. His eyes looked a little hard.

Who are you? I wondered. A cautionary tale? Or a model of how to be?

I clicked through to more pictures of him. There he was as a boy, suddenly lamblike, with spilling dark curls and protruding ears. There he was as a young man, standing upright in a rowboat. His shoulders had filled out and he was biting his lower lip in a way that could almost be classified as sultry. There he was as a grandfatherly old man, sitting in an armchair, scratching a shaggy, white dog. I saw links to articles and books he had written. Fish-collecting guides, taxonomic studies of the fishes of Korea, of Samoa, of Panama. But there were also essays about drinking and humor and meaning and despair. He had written childrens books and satires and poems and, best of all, for the lost journalist seeking guidance in the lives of others, an out-of-print memoir called The Days of a Man, packed tight with so many details about said days of said man it had to be broken into two volumes. It was nearly a century out of print, but I found a used-book dealer who would sell it to me for $27.99.