THE AUTHOR

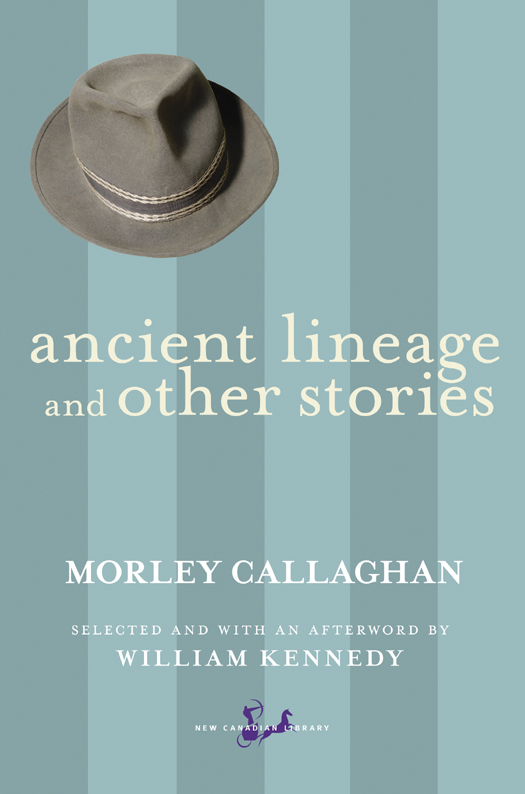

MORLEY CALLAGHAN was born in Toronto, Ontario, in 1903. A graduate of the University of Toronto and Osgoode Law School, he was called to the bar in 1928, the same year that his first novel, Strange Fugitive, was published. Fiction commanded his attention, and he never practised law.

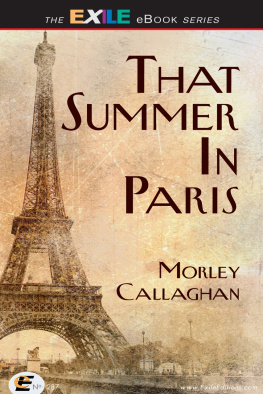

While in university, Callaghan took a summer position at the Toronto Star when Ernest Hemingway was a reporter there. In April 1929, he travelled with his wife to Paris, where their literary circle of friends included Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Joyce. That Summer in Paris is his memoir of the time. The following autumn, Callaghan returned to Toronto.

Callaghan was among the first writers in Canada to earn his livelihood exclusively from writing. In a career that spanned more than six decades, he published sixteen novels and more than a hundred shorter works of fiction. Usually set in the modern city, his fiction captures the drama of ordinary lives as people struggle against a background of often hostile social forces.

Morley Callaghan died in Toronto, Ontario, in 1990.

Copyright 2012 by the Estate of Morley Callaghan

Afterword copyright 2012 by William Kennedy

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Callaghan, Morley, 1903-1990

Ancient lineage and other stories / Morley Callaghan.

(New Canadian library)

eISBN: 978-0-7710-1819-0

I. Title. II. Series: New Canadian library

PS 8505. A 43 A 52 2012 C 813.52 C 2012-905252-3

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited

One Toronto Street

Toronto, Ontario

M 5 C 2 V 6

www.mcclelland.com/NCL

v3.1

CONTENTS

THE NEW CANADIAN LIBRARY

General Editor: David Staines

ADVISORY BOARD

Alice Munro

W.H. New

Guy Vanderhaeghe

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

The text for the stories in this collection is Morley Callaghan: The Complete Stories (Exile Editions, 2005). The original publication date of each story follows the text.

A GIRL WITH AMBITION

A fter leaving school when she was sixteen, Mary Ross worked for two weeks with a cheap chorus line at the old La Plaza, quitting when her stepmother heard the girls were a lot of toughs. Mary was a neat, clean girl with short, fair curls and blue eyes, looking more than her age because she had very long legs, and knew it. She got another job as cashier in the shoe department of Eatons, after a row with her father and a slap on the ear from her stepmother.

She was marking time in the store, of course, but it was good fun telling the girls about imaginary offers from big companies. The older salesgirls sniffed and said her hair was bleached. The salesmen liked fooling around her cage, telling jokes, but she refused to go out with them: she didnt believe in running around with fellows working in the same department. Mary paid her mother six dollars a week for board and always tried to keep fifty cents out. Mrs. Ross managed to get the fifty cents, insisting every time that Mary would come to a bad end.

Mary met Harry Brown when he was pushing a wagon on the second floor of the store, returning goods to the department. Every day he came over from the mail-order building, stopping longer than necessary in the shoe department, watching Mary in the cash cage out of the corner of his eye. Mary found out that he went to high school and worked in the store for the summer holidays. He hardly spoke to her, but once, when passing, he slipped a note written on wrapping paper under the cage wire. It was such a nice note that she wrote a long one the next morning and dropped it in his wagon when he passed. She liked him because he looked neat and had a serious face and wrote a fine letter with big words that were hard to read.

In the morning and early afternoons they exchanged wise glances that held a secret. She imagined herself talking earnestly, about getting on. It was good having someone to talk to like that because the neighbors on her street were always teasing her about going on the stage. If she went to the butcher to get a pound of round steak cut thin, he saucily asked how was the village queen and actorine. The lady next door, who had a loud voice and was on bad terms with Mrs. Ross, often called her a hussy, saying she should be spanked for staying out so late at night, waking decent people when she came in.

Mary liked to think that Harry Brown knew nothing of her home or street, for she looked up to him because he was going to be a lawyer. Harry admired her ambition but was shy. He thought she knew how to handle herself.

In the letters she said she was his sweetheart but never suggested they meet after work. Her manner implied it was unimportant that she was working at the store. Harry, impressed, liked to tell his friends about her, showing off the letters, wanting them to see that a girl who had a lot of experience was in love with him. Shes got some funny ways but Ill bet no one gets near her, he often said.

They were together the first time the night she asked him to meet her downtown at 10:30. He was waiting at the corner and didnt ask where she had been earlier in the evening. She was ten minutes late. Linking arms, they walked east along Queen Street. He was self-conscious. She was trying to be very practical, though pleased to have on her new blue suit with the short stylish coat.

Opposite the cathedral at the corner of Church Street, she said, I dont want you to think Im like the people you sometimes see me with, will you now?

I think you are way ahead of the girls you eat with at noon hour.

And look, I know a lot of boys, but they dont mean nothing. See?

Of course, you dont need to fool around with tough guys, Mary. It wont get you anywhere, he said.

I cant help knowing them, can I?

I guess not.

But I want you to know that they havent got anything on me, she said, squeezing his arm.

Why do you bother with them? he said, as if he knew the fellows she was talking about.

I go to parties, Harry. You got to do that if youre going to get along. A girl needs a lot of experience.

They walked up Parliament Street and turned east, talking confidently as if many things had to be explained before they could be satisfied with each other. They came to a row of huge sewer pipes along the curb by the Don River bridge. The city was repairing the drainage. Red lights were about fifty feet apart on the pipes. Mary got up on a pipe and walked along, supporting herself with a hand on Harrys shoulder, while they talked in a silly way, laughing. A night watchman came along and yelled at Mary, asking if she wanted to knock the lights over.