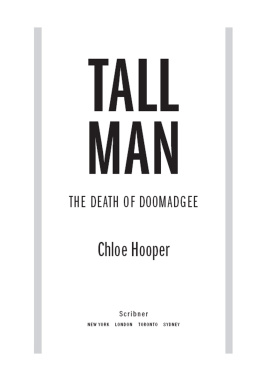

What they are running from, and to, and why.

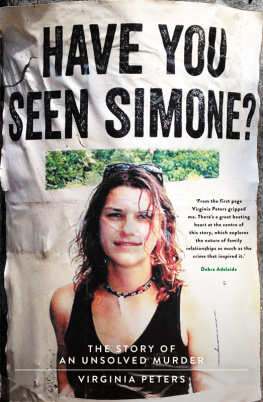

Prior to this books publication, the publisher received a letter from solicitors acting for one of the subjects in this book which raised a threat of defamation proceedings. For the avoidance of any doubt, this book does not and cannot say who is guilty of murdering Simone Strobel. No one has ever been charged with any offence relating to Simones death by the New South Wales Police Force.

Readers must not read anything in this book as concluding or even inferring that any individual mentioned in this book is guilty of murder.

This book presents facts taken from discussions with those who were present in the locality when Simone disappeared and with members of investigating authorities, and from evidence presented at, as well as the findings of, the coronial inquest into her death.

The circumstantial evidence and facts set out in this book do, of course, mean that there is a suspicion (one shared by the New South Wales Police Force) about who may have murdered Simone, but neither the author nor the publisher state anything further than this.

Monday, 14 February 2005

I first saw Simone in a cafe called Succulent, a few streets from the main beach of Byron Bay.

I came here most mornings after my run to the lighthouse. Even though the cafe looked out onto a car park, the concrete was as pleasing as the white sand that fringed the bay. Rows of cars vibrated in the heat, and in the distance the occasional bright green fronds of a Bangalow palm stood out like a beach umbrella against an ocean of blue sky. Inside, the place had a Moroccan feel: mosaic table tops, their iron feet curling like Persian slippers on the polished concrete, rusted tin lanterns hanging from the ceiling.

The swarthy barista looked up and raised two fingers at me. I shook my head and raised one back. One cap; no mother today . Id not called herand it would never have occurred to her to ring me. I was probably reacting to that, but maybe I was also preparing for the possibility she might not always be around.

Sitting in our usual spot, I surveyed the room. Nearby, a couple of women with yoga mats looked limpid-eyed after a session of ashtanga upstairs; at another table two men caved over plates of spinach and eggs. They had a clean, salty look about the earssurfers, probably. A few more tables of twos and threes created a constant buzz. The waiter arrived at my table with a coffee and a wink: No mum today?

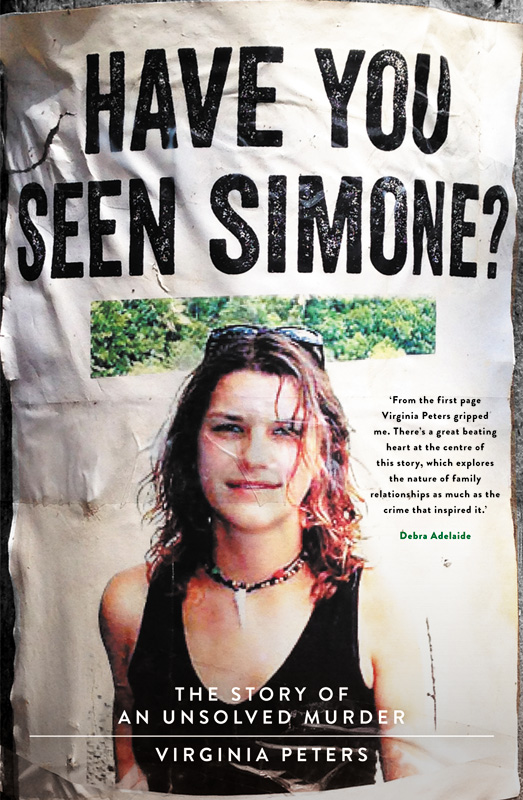

I mumbled something about us taking a break and reached for the Sydney Morning Herald , my daily fix of the real world, miles from here, when I noticed a piece of paper just below the coffee machine, taped to the white tiles of the counter front. Across the top of the A4 sheet, above a photograph, ran a heading in bold print: HAVE YOU SEEN SIMONE? The use of the girls Christian name seemed to imply I might know her.

It was not a good place to attach a notice. Legs brushed against her, blocking my line of sight. I waited for them to move, and narrowed in again.

She was standing on a beach, surrounded by thick white sandthe fine, floury sort that formed shadowy clumps. The bower of a tree drooped behind her, its stalky branches emanating from either side of her head, just above her ears. She was already statuesque, but with this suggestion of antlers she seemed even more so, like a proud young deer, shoulders and neck erect, face strongly boned, but soft enough to make her incredibly pretty. MISSING SINCE LAST FRIDAY . There was a mobile number to call.

Whoever had made this poster had kept it simple. A parent would have been more pleading, I thought. I wondered whose number it wasa friends? A lovers?

I went back to my coffee and paper , scanning the pages for news, only to find my eyes returning to the counter. There was something interesting about this girl, the vulnerability of her stance, the way her arms hung loosely at her sides.

Dont waste your time worrying, I told myself. Shes probably very self-assured. Shell show up somewhere. She probably already has, hung-over after a weekend binge. She might even be secretly thrilled to find herself the subject of a poster campaign, as though suddenly cast as the central character in a film noir . Thats what would most likely happen.

But then again, something told me it might not. She looked so alone against the counters white tiles, the white paper, the clumpy white sand, too surrounded by space, by a sort of nothingness.

*

I spent the rest of the day at home writing. The short story form, I found, seemed to suit my circular way of thinking. I wore small holes in the page thinking about problems associated with love and domesticity in modern society. I was very self-conscious about my subject matter. Like many writers, I wrote fiction that was largely autobiographical, with wet patches of imagination.

I was doing a creative writing degree at university. The last time I saw my supervisor, hed held the edges of my story as though it might stain his fingers. I cant read this, hed said. These people are just awful.

I felt a flash of sweat beneath my arms. I cant stand them either, I said with a tinkering laugh, as though he and I were co-conspirators. Everything he wrote was about crime, prostitutes, crooked cops.

This guy, hes such a prat, he said, waving the pages high in the air. Why in Gods name does she stay with him?

I was shocked. I wanted to laugh out loud. My husband? Was Rodd really a prat? Id never considered this before. I couldnt wait to tell him. Wed laugh our heads off.

Your problem is that nothing ever happens in your stories. Nothing . He wheeled across the carpet in his roller chair and leaned in close to me. Write about something you really care about.

What did I really care about? Family? My mother? That night, I went home to my three children and my prat husband and looked at them. Critically. I knew the theory was that people wrote stories either to make sense of life or to give it some meaning. Something would have to happen to this family for me to make sense of it, I decided, and possibly something catastrophic. But I felt fairly certain that nothing ever would. I had an innate confidence we would remain perfectly comfortable, remote, coddled from the world of misfortune to the point of ignorance. And although this was a blessing, I felt numbed by it, as though this safe world I inhabited was ultimately sterile and insignificant.