ALPINE WARRIORS

Bernadette McDonald

CONTENTS

He who is in pursuit of a goal will remain empty once he has attained it.

But he who has found the way will always carry the goal within him.

Nejc Zaplotnik, Pot

Introduction

I PAWED THROUGH THE SLUSH from a late-summer snowstorm, searching for the cable attached to the narrow ridge leading to the top of Triglav, Slovenias highest mountain. Stepping carefully, I made my way up toward Alja Tower, the small metal building that sits on the summit. A modest structure, it is a symbol to all Slovenians of their territorial sovereignty. In response to foreign oppression, the priest Jakob Alja actually bought the summit of Triglav in 1895 for one florin, as if to say, We are the masters of our own lands. When I reached the summit, I could hardly believe my eyes. Dozens of people were gathered near the tower, laughing and talking, eating lunch and celebrating their ascent. Young students threw snowballs and clowned for their cameras. An elderly woman, flanked by her two mountain guides, wept quietly. A radiant smile lit the face of a man with neither arms nor legs.

I walked up to a group of young climbers. Is this some kind of national holiday? I asked.

Not at all, a particularly athletic woman replied. Its just the weekend.

But why are there so many people up here?

Because its the weekend and we have time, she repeated, smiling patiently. We are Slovenians and this is Triglav. It is our duty to climb it. Every Slovenian must climb it at least once.

I gazed over at the crying woman, who was possibly relieved that she had reached the top or maybe fearful of the descent to come. Then I looked back at the man with no limbs, whose friends loved him enough to carry him up two thousand metres in less than ideal conditions. I tried to imagine how they felt on the top of their Triglav the national symbol of Slovenia. And I wondered about the character of a nation that feels its citizens must climb its highest mountain to be truly Slovenian.

For the next few years I immersed myself in the rich, complex, contradictory and often divisive world of Slovenian climbers, who are among the finest alpinists in the world. Sometimes we talked over glasses of fine local wine; sometimes I climbed with them. These alpinists had made some of the worlds most impressive climbs: Makalu South Face, Lhotse South Face, Everest West Ridge Direct, Dhaulagiri South Face, and many more. Edmund Hillary is a household name, but many great Slovenian climbers and a few from neighbouring Croatia and Bosnia are almost unknown, even though their remarkable achievements formed the backbone of Himalayan climbing for 25 years, during a golden era of alpinism from the mid-1970s onward. That explosive and exciting period of bold ascents was not an accident. The climbers of the time were blessed with legendary leadership, infused with dogged determination, supported by national training programs, and inspired by feelings of solidarity that propelled them up some of the most iconic climbs in history.

Although I dont speak their language and I live 13,000 kilometres away, I felt drawn to both the history and the heroism of this community of climbers. As I learned more about Slovenian alpinists climbing at the end of the Second World War and onward to more recent times, I found some common threads in their wildly different personalities. The first is a self-sufficiency and drive forged by the history of a country under almost constant political threat and deeply wounded by internal conflict. Slovenian climbers, like their Croatian and Serbian neighbours, were shaped by the chaos of two world wars, foreign occupation, dictatorship, religious intolerance and, ultimately, civil war.

The second common thread is their fierce ability to defend their nation, language, culture and, as alpinists, their reputations sometimes, even among themselves. In the postSecond World War years, when the standard of living was low, sports and the arts provided rare opportunities to prove individual excellence. Slovenian climbers competed for coveted positions on Yugoslavian expeditions, and they performed well at times even better than their European rivals.

Third, every Slovenian climber I have met seems indelibly stamped by the nations landscape, with its deeply shaded, forested valleys, impossibly clear rivers, cerulean blue lakes and endless supply of mountains steep, shimmering, limestone towers rising up in every direction. Most climbers freely admit that their souls are defined by their beloved home mountains, which have always had a symbolic almost mythical importance in Slovenia.

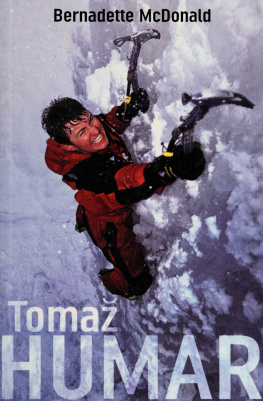

Finally, another thread binds Slovenian climbers. It seems an unlikely one: a man and his book. Although the importance of this man and his writing took me some time to fully appreciate, I first became aware of him in 2006 while doing research for a biography of Toma Humar, one of Slovenias most controversial climbers.

I remember the day well. Toma stood at his living-room window with a book in his hand. The late-afternoon light shone gold on its worn cover. He fondled it, his oversized hands turning it over and over. He handed it to me. The pages were thin and torn. Some were stained. Wine, I think.

One of my prized possessions, he said. Then, he began to explain how this slender volume written by Slovenian alpinist Nejc Zaplotnik had taught him, inspired him and given him a reference point for his life as a climber. He told me that the book, Pot, had been written in 1981, just 13 years after Toma was born. Toma and Nejc never met, yet the authors words and his feelings and values had resonated for Toma in the most profound way.

What does it mean? I inquired.

Pot ? It means the Way or the Path.

Can you explain a little more? I asked.

Its a way of living, like a philosophy. Nejc wrote about how he felt about the mountains and people and love, about making the most of his life. Its incredible, how he wrote. He was a poet, an artist, a climber, all wrapped in one. Here, take a listen: But now, in this moment, a harmony that we have almost forgotten has been reached: nature, body and mind have become one. They mutually serve and complete each other.

I knew Toma well enough to be somewhat skeptical of his gushing. Toma was unusual, to say the least. He experimented with various forms of spirituality; was equally comfortable with Catholicism, Buddhism, and the third eye; and claimed he could even communicate directly with a mountain face. This volume was probably some kind of religious self-help handbook. Still, it seemed important to him, so I made a note of it and promised myself to look into it further.

A year later, I was with another Slovenian climber, Silvo Karo, seated on a limestone slab at the top of Ania Kuk in Paklenica, the Croatian climbing paradise. We had just climbed a 350-metre route that seemed a cakewalk to rock-master Silvo but was beyond my wildest dreams. My arms were pumped with blood, my feet were screaming inside my tight climbing shoes, and my brain was fuzzy from dehydration. But out of the fog, I realized that Silvo, while calmly coiling the rope and gazing out to the valley below, was also talking about some book. It was Pot . Again, Pot . I could sense how important it was to Silvo by the tone in his voice and the words he used to describe it. Words like values and authentic and wise.

Interesting. Although both Slovenian and both climbers, its hard to imagine two individuals less alike than Silvo Karo and Toma Humar. Silvo, the taciturn pragmatist, and Toma, the romantic dreamer. And yet they were both in awe of this book and its author.

I began searching for an English edition of Pot , to no avail. A translation did not exist.