THE LIFE OF MARK TWAIN

THE MIDDLE YEARS

Copyright 2019 by The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65211

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. First printing, 2019.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Scharnhorst, Gary, author.

Title: The life of Mark Twain : the middle years, 1871-1891 / by Gary Scharnhorst.

Description: Columbia : University of Missouri Press, [2019] | Series: Mark Twain and his circle | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2018049235 (print) | LCCN 2018055461 (ebook) | ISBN 9780826274304 (e-book) | ISBN 9780826221896 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Twain, Mark, 1835-1910. | Twain, Mark, 1835-1910--Homes and haunts. | Authors, American--19th century--Biography. | Humorists, American--19th century--Biography.

Classification: LCC PS1331 (ebook) | LCC PS1331 .S24 2019 (print) | DDC 818/.409 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018049235

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Typefaces: Clarendon and Jenson

This book was published with the generous support of

The Missouri Humanities Council

and

The State Historical Society of Missouri

Mark Twain and His Circle

Tom Quirk and John Bird, Series Editors

Illustrations

CHAPTER 1

Elmira, Hartford, and on the Stump

The farm is perfectly delightful, this season. It is as quiet & peaceful as a South-sea island.

Samuel Clemens to W. D. Howells, August 9, 1876

IN MARCH 1871 Samuel Clemens faced a daunting future. He had washed out as the managing editor of the Buffalo Express and sold his one-third interest in the newspaper at a loss. As a result, he was thousands of dollars in debt. His writing of the book that would become Roughing It (1872) had stalled and was months behind schedule. He had grown to loathe Buffalo and its harsh winters, so he had listed his house for sale for ten thousand dollars less than his father-in-law had paid for it little more than a year before. His wife Olivia, a near invalid, suffered from nervous prostration, and their infant son Langdon was chronically ill. Sams most recent release, Mark Twains (Burlesque) Autobiography (1871), had been a critical and commercial flop. Rumors were afloat, fueled by its failure, that he was written out and reduced to mining slag from an exhausted vein. He depended for a livelihood on royalties from The Innocents Abroad (1869) but its sales were fast declining after its initial appearance two years earlier. And Bret Harte, his not-so-friendly rival, had recently emigrated from California and signed the most lucrative contract to date in the history of American letters to write exclusively for the firm of Fields, Osgood and Company, the publishers of the Atlantic Monthly. Sams own prospects seemed dreary to dismal by comparison. He could not have predicted that as soon as Harte signed this contract his career went into a death spiral. As Howells later remarked, when Harte moved east he lost the power of observation. Or, as he might have said, Harte left his eye in San Francisco.

The interlude the Clemenses spent with Olivias family in Elmira during the spring and summer of 1871 proved to be a welcome but temporary respite from their woes. As he notified his publisher Elisha Bliss and brother Orion two days after their arrival, We are all here, & my wife has grown weak, stopped eating, & dropped back to where she was two weeks ago. But weve all the help we want here. Livys prognosis had not improved a week

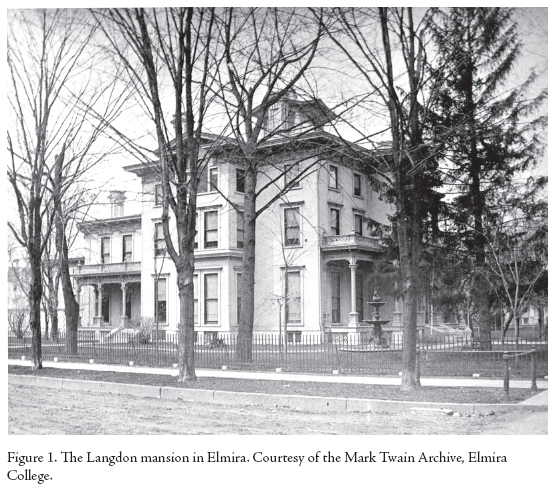

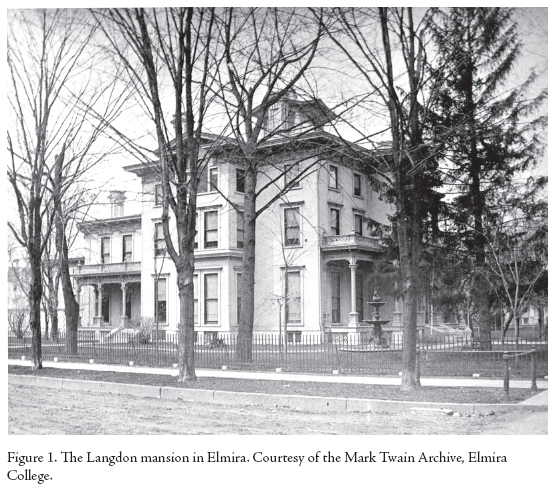

No sooner had Sam dropped his bags at the Langdon mansion on Main Street than he began to plot a way forward.

He desperately needed to complete his overdue book about the West, which had reached a standstill after only 168 pages of manuscript, about one-tenth the length required for a subscription book. He soon settled into a routine. Most days he escaped the din of the city and the crying of his son by climbing Watercure Hill, two miles east of the city, to the house at Quarry Farm, offered him as a hideaway by his in-laws Theodore and Susan Crane. The retreat stood several hundred feet above the valley, with a view of Elmira, the Chemung River, and the distant blue hills of northern Pennsylvania.

Relieved of nursing duties by the Langdon servants and spared the distractions that plagued him in Buffalo, Sam shortly found his working groove again. He was joined on March 24, less than a week after his arrival in Elmira, by his old Nevada friend Joe Goodman, and the two writers began to worry over their respective projects like stray dogs over bones. Goodman wrote loads of poetry while I wrote the yet untitled western narrative, Samtestified years later, & between whiles they played cards or collected rocks and fossil shells from the quarry on the farm. On his part, Goodman remembered that Sam

was awfully tickled at my coming and wanted to pay me a salary to remain until he had finished the work, saying he had lost Pacific Coast atmosphere and vernacular, but that I brought it all back to him afresh. I told him I couldnt stop a great while, but that I would stay with him as long as I could, if he would agree not to speak about pay again. So every morning for a month or more we used to tramp together up to the Quarry Farm, about two miles from town, where he was doing his writing in the unoccupied farmhouse.

Sam averaged about twenty pages of sixty to seventy words per page, or about twelve hundred to fourteen hundred words of manuscript per day, according to Goodman. Sams goal was from ten thousand to twelve thousand words a week. More to the point, Sam solicited Goodmans opinion of his work in progress. As Goodman would later comment,

I recollect his giving me the manuscript of Roughing It to read one afternoon when I was visiting him.... He made a great hit with Innocents Abroad and he was afraid he would not sustain his newly acquired reputation. When I began to read Sam sat down at his desk and wrote nervously. For an hour I read along intently, hardly noticing that Sam was beginning to fret and shift about uneasily. At last he could not stand it any longer and jumping up, he exclaimed Damn you, you have been reading that stuff an hour and you havent cracked a smile yet. I dont believe Im keeping up my lick.

Goodman may fairly be regarded as the godfather of Sams second travel book, although, as he allowed, It was a long while before he grew calm enough to accept the assurance of my appreciation of his work.

They briefly considered cowriting a satirical political novel. Sam contacted Isaac Sheldon, the publisher who had issued his

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.