Yellowstone National Park, 1881

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Contents

After placing about fifteen shots where they were most needed, I had the herd stopped, and the buffalo paid no attention to the subsequent shooting.

V ICTOR G RANT S MITH

Vic Smith, a hunter, lifted his head above a rise on the plains floor, peering down at several hundred buffalo in the valley of the Redwater River. The Montana winter of 1881 was frigid, all the more so because Smith lay prone in the snow, two Sharps buffalo rifles and several bandoleers of cartridges spread out on a tarp beside him. Smith was careful to stay downwind and wore a white sheet to conceal him from the nearest animals, three hundred yards away. For a while he just watched, his experienced eyes studying the herdpicking out the leaders, anticipating movements, carefully planning his first shot. It all looked perfect, the ideal stand.

Finally Smith reached for one of the Sharps, working the lever to chamber a four-inch brass shell. Supporting the stout barrel across his arm, Smith sighted carefully on the old cow that he knew led the herd. He aimed at a spot just in front of her hip, then fired.

The report of the big gun thundered across the wide plain, and a cloud of acrid smoke temporarily obscured the herd. Smith did not look to see if he had hit his targethe knew he had. Instead he set the smoking rifle on the tarp and loaded the second gun, then pulled it snug to his shoulder. He alternated rifles each shot; otherwise the barrels became so hot that they fouled. In Texas, hed heard, buffalo hunters sometimes urinated on their guns to cool them, but in Montana, winter did the work.

The second Sharps ready, Smith looked up to find exactly what he expected. His first shot had found its precise target in front of the cows hip. When hit in that spot, Smith knew, the animal could not run off but instead would just stand there, all humped up with pain. As Smith intended, other members of the herdthe old cows children, grandchildren, cousins, and auntswere already starting to mill about, confused, some sniffing at the blood that seeped from the cow.

Smith now sighted on another old cow on the opposite side of the herd, marking the same target in front of the hip. He fired again.

Smith worked deliberately, never rushing, a shot about once every thirty seconds. Every bullet was strategic. Most of the early targets were cows, though occasionally he picked off a skittish bull that looked ready to bolt. After placing about fifteen shots where they were most needed, he would later recall, I had the herd stopped, and the buffalo paid no attention to the subsequent shooting. Experienced hunters like Smith called it tranquilizing or mesmerizing the herd.

An hour later he was done. Below Vic Smith in the valley of the Redwater lay 107 dead buffalo. In the 1881 season he would kill 4,500.

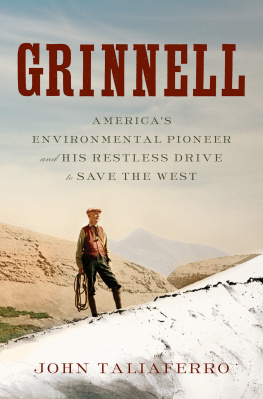

T HE STORY OF HOW THE BUFFALO WAS SAVED FROM EXTINCTION IS one of the great dramas of the Old West. More profoundly, it is a story of the transition from the Old West to the Newa transition whose battles are still fought bitterly to this day. The story is personified in a man, little known today, by the name of George Bird Grinnell. Grinnell was a scientist and a journalist, a hunter and a conservationist. In his remarkable life, Grinnell would live the adventures of the Old West even as he helped to shape the New.

I love stories about the Old West, first and foremost, because they are vivid and compelling. For two centuries, the West has been at the core of our American narrative, with characters that are archetypal, storied events that have become parables for broader national lessons, and a landscape that is not mere backdrop, but a character itself, from beautiful muse to mortal enemy. The animals too have their own epic tales: bears, beaver buffalo.

Beyond their visceral grip, however, the greatest gift of stories from the Old West is their screaming relevance in our lives today. So it is with the remarkable story of George Bird Grinnell and the battle to save the buffalo.

We live, today, in one of the most divisive eras in our national history. So divided are we, it has become nearly impossible to conduct discussions that are vital to our future as a people and as a planet. Many people have made up their minds about such topics as climate change, with little ability for the genuine give and take of true discussion. Debates, meanwhile, devolve quickly into cable-news shouting. Increasingly we self-select on the internet and social media to surround ourselves with the like-minded, whatever our views. How do we begin to dig ourselves out, to salvage the thoughtful discourse in civil society that is the lifeblood of our American democracy, so that we can grapple with the challenges we all face?

In three decades of studying history and working in public policy, one lesson I have learned is that oftentimes the most powerful argument in contemporary debate is a historical example. Lessons and lore from the past can often be persuasive even as a contemporary corollary remains too controversial for rational discussion, too freighted with baggage for an open mind.

What lessons does George Bird Grinnell teach us that are relevant to our lives today? What is this book about?

The first attribute of Grinnell that leaps out is his ability to see ahead of his time. Between roughly 1864 and 1884, an American buffalo herd numbering approximately 30 million was wiped from the face of the planet, leaving a few dozen harried animals in the wild, most of them in an unprotected Yellowstone National Park. Most Americans today agree that was a tragedy and wonder how it could have happened. Yet the more I studied Grinnell and his place in the nineteenth century, the more it occurred to me that the anomaly was not the destruction of the buffalo. Indeed, it became apparent that the destruction of the buffalo was perfectly consistent with the pervasive nineteenth century view of nature as something to be conquereddug up or shot down.

What is amazing about Grinnell is that he had such a strikingly different visionfor a West where wild places and wild animals had intrinsic value and should be protected. Part of Grinnells ability to see the future came from his study of the pastand from respect for science. His first trip to the Great Plains took place in 1870, when he accompanied a group of Yale dinosaur hunters (protected by the US Cavalry as they dug for bones). Buffalo were still so numerous that a herd blocked the passage of his train. Yet Grinnell also discovered the fossils of ancient miniature horses, camels, and six-horned dinosaurs. To Grinnell, extinction was far from impossible, but rather something he had studiedtouched with his handsand knew had happened in the past. It shaped fundamentally how he saw what might happen in the future.