SPARE THE BIRDS!

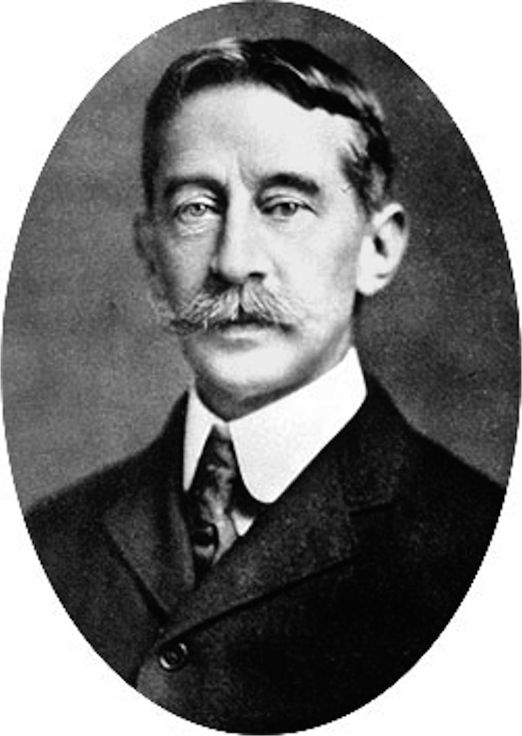

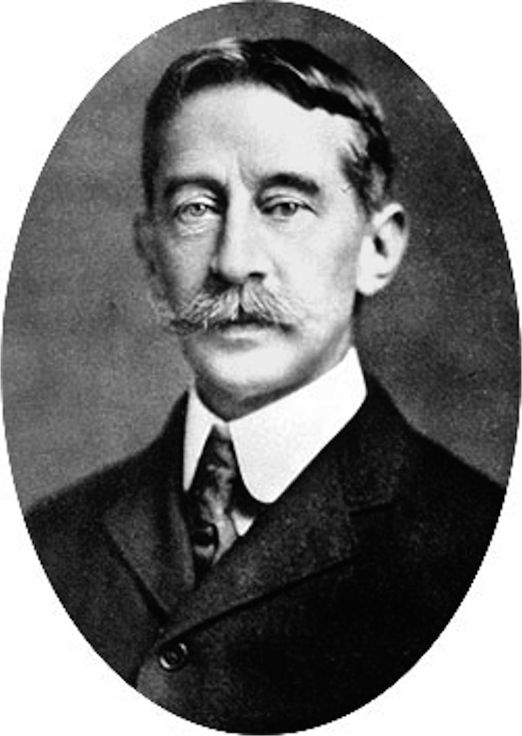

George Bird Grinnell (18491938)

SPARE the BIRDS!

George Bird Grinnell and the First Audubon Society

Carolyn Merchant

Carolyn Merchant

Published with assistance from Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

Copyright 2016 by Carolyn Merchant.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

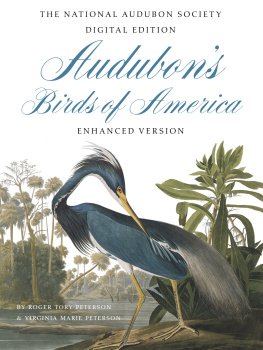

Jacket image and color plates of birds are from the National Audubon Society Baby Elephant Folio edition of Audubons Birds of America, with text by Roger Tory Peterson and Virginia Marie Peterson (New York: Abbeville Press, 1981).

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Designed by Amber Morena

Set in Arno Pro type by Motto Publishing Services

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016933636

ISBN 978-0-300-21545-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Frontispiece: George Bird Grinnell ()

For Charlie

Contents

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL

R[OBERT] W. SHUFELDT

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL

Preface

When explorer and conservationist George Bird Grinnell (18491938) started The Audubon Magazine in 1887, a year after he founded the Audubon Society, he introduced each issue with an editorial that he wrote himself about the life and character of John James Audubon (17871851). To bring birds to the publics attention, he also chose one of Audubons bird paintings, which he himself described, as a special feature of each issue. Grinnells knowledge of Audubon was deeply influenced by his experiences growing up on Audubons estate in New York City, where he attended the school taught by Audubons widow, Lucy. The impact of Lucy, John James, and their two sons on Grinnells desire to preserve wildlife was profound and is reflected in Grinnells work. The Audubon Magazine, however, lasted only two years, after which for practical reasons Grinnell felt obliged to dissolve both the society and the journal. But within five years, women, along with men, took on leadership roles in reviving the Audubon movement.

In this book, I analyze Grinnells work to found the 1886 Audubon Society, his publication of The Audubon Magazine, and the gendered issues underlying his role in saving avifauna. A major goal of the following text is to reprint Grinnells serialized biography of Audubon and other writings in the magazine (making them available to the public) and to interpret them in the context of Grinnells achievements.

A primary reason that Grinnells biography of Audubon has not been recognized as such is that Grinnell was the sole editor of The Audubon Magazine and his editorials were unsigned. In fact, from the time that Grinnell took over the editorship of Forest and Stream in 1880 (after having moved up in 1876 from his position as its natural history editor), he made it his practice not to sign his editorials. He strongly believed, according to Grinnell historian John Reiger, that as editor he should not add his name, as doing so would personalize the content and thereby detract from the authority of the magazine itself. He was scrupulous, however, in attributing other articles and letters in both magazines to their authors. In his editorials, he also carefully placed selections from other authors in quotation marks.

Grinnell listed the address of The Audubon Magazine (which was published by Forest and Stream Publishing Company) as 40 Park Row, New York City, NY, asking that all letters and articles be sent to that address. Grinnell was a prodigious writer and editor as well as a public champion for conservation of wildlife. But ultimately the task of editing two journals (one weekly, the other monthly) and maintaining the Audubon Society and the Boone and Crockett Club, which he cofounded with Theodore Roosevelt the same year he started publishing The Audubon Magazine, took too much of his time and energy. By early 1889 he felt obliged to discontinue both the society and the magazine (see ).

In , I discuss Grinnells life on Audubons New York City estate (which by then was known as Audubon Park) and the forces that shaped his character and goals. Here I draw on a memoir written by Grinnell that describes his life up until 1883 and was deposited at Yale University due to the efforts of historian John Reiger. I am deeply grateful to John for his very helpful comments on Grinnells background and writings. I also discuss the gendered issues underlying conservation, including the shooting, use, and preservation of birds that led to Grinnells founding of the Audubon Society, the publication of The Audubon Magazine (18871889), the concerns it covered during its two years of existence, and the factors that led to its cessation in 1889. I then look at the revival of the Audubon movement in the mid-1890s in the form of state Audubon societies and the founding of a new journal, Bird-Lore. Here I emphasize the leadership roles played by both women and men and the passage of legislation to stem the decline of birdlife.

In by Robert W. Shufeldt and the editorials written by George Bird Grinnell pertaining to Audubons life, character, and incidents, making these documents available to the public. Another major, unrecognized contribution is Grinnells serialized biography of Audubons predecessor and fellow artist Alexander Wilson (17661813) that occupied the final eight issues of The Audubon Magazine. Grinnells attention to the contributions of Wilson and Audubon brought the two great founders of American ornithology to the attention of the American public.

In , Grinnells Monthly Birds, I introduce and reproduce Grinnells chosen Audubon birds, along with the descriptions he wrote himself but likewise left unsigned. Appearing each month, and written for a popular audience, as a group they constituted an early field guide for a public beginning to be aroused by the plight of Americas vanishing birds. As these descriptions attest, Grinnell was not only a keen observer of birds, but also adept at writing potrayals of avifauna, a skill honed during his many years as natural history editor and then editor of Forest and Stream. In reproducing the text, spelling was slightly altered as needed.

In the epilogue, I assess Grinnells achievements with respect to his efforts to preserve birdlife, and I briefly review his many other outstanding accomplishments. The book also includes timelines of the lives of John James and Lucy Audubon and of George Bird Grinnell that reveal the continuity of their efforts to illustrate, write about, and preserve birdlife. In an appendix, I also discuss the complex technologies of lithography and photography that allowed both Audubon and Grinnell to publish images of the birds of America. As a whole the book offers an important perspective on three individuals who were critical to the study and conservation of birds in America: Alexander Wilson, John James Audubon, and George Bird Grinnell. It also highlights women and men who supported and promoted their work.

Next page

Carolyn Merchant

Carolyn Merchant