Charles M. Russell:

The Life and Legend of Americas Cowboy Artist

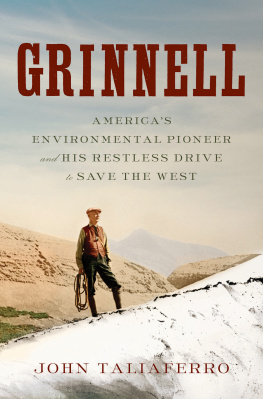

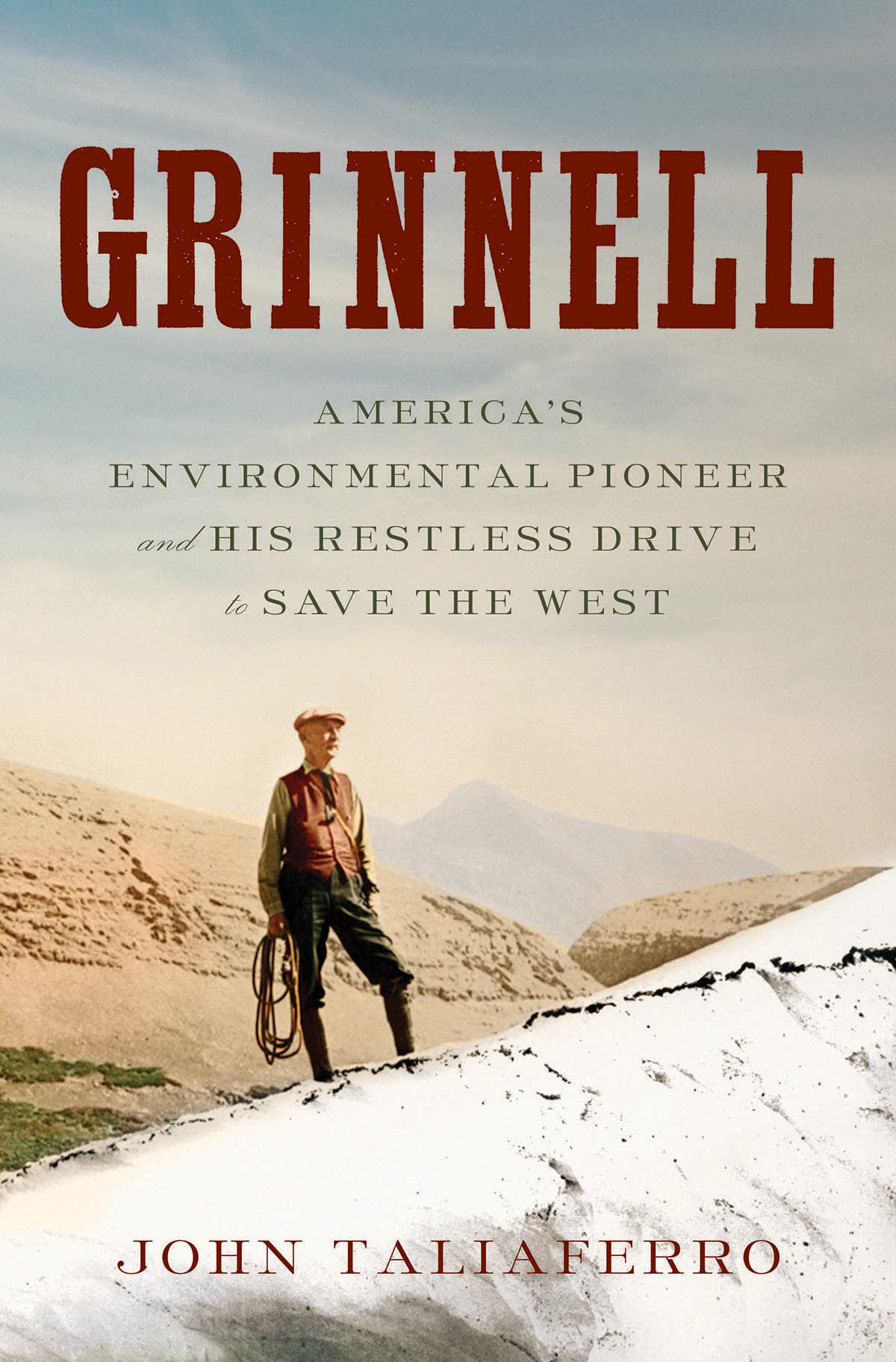

GRINNELL

AMERICAS ENVIRONMENTAL PIONEER AND HIS RESTLESS DRIVE TO SAVE THE WEST

JOHN TALIAFERRO

Copyright 2019 by John Taliaferro

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by JAM Design

Production manager: Anna Oler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Taliaferro, John, 1952 author.

Title: Grinnell : Americas environmental pioneer

and his restless drive to save the West / John Taliaferro.

Description: First edition. | New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, A Division of W. W. Norton & Company, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019002370 | ISBN 9781631490132 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Grinnell, George Bird, 18491938. | Natural historyWest (U.S.) | West (U.S.)History18601890. | West (U.S.)History18901945. | NaturalistsUnited StatesBiography. | ConservationistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC QH31.G74 T35 2019 | DDC 508.78dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019002370

ISBN 9781631490149 (ebook)

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

FOR

John Stillman

(19452013)

Happy, especially, is the sportsman who is also a naturalist; for as he roves in pursuit of his game, over hills or up the beds of streams where no one but a sportsman ever thinks of going, he will be certain to see things noteworthy, which the mere naturalist would never find, simply because he could never guess that they were there to be found. I do not speak merely of the rare birds which may be shot, the curious facts as to the habits of the fish which may be observed, great as these pleasures are. I speak of the scenery, the weather, the geological formation of the country, its vegetation, and the living habits of its denizens.

CHARLES KINGSLEY , Glaucus (1855)

CONTENTS

A Blackfeet is a Blackfoot, but not every Blackfoot is a Blackfeet. The Blackfoot Indians are made up of four bands: Blackfoot, Blood, Northern Piegan, and Southern Piegan. The first three of these bands reside in Canada. The Southern Piegans, also called Blackfeet, live on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana. Grinnell addressed the Southern Piegans simply as Piegans, ( p gans ) or as Blackfeet. Herein the author honors Grinnells interchangeable usage of Blackfeet and Piegan and also allows Grinnells usage of Blackfoot as an adjective or to describe an individual member of the Blackfeet band. Today, however, an individual member of the American Blackfeet, or Piegans, is not properly a Blackfoot, except with respect to his or her membership in the larger Blackfoot confederacy. In the course of daily life, he or she is a Blackfeet.

The term Indian , to describe indigenous people of North America, was in common usage in Grinnells time, and it is nearly as common today, among both Indians and non-Indians. The author, who is white, chooses to use it in its historical context, while acknowledging that Native American (or in Canada, First Nations ) is a more accurate and more respectful identifier of the people who inhabited the continent long before Europeans stepped ashore.

Transcribing Grinnells letters and diaries, the author has taken occasional liberties with spelling, capitalization, and punctuation for the sake of consistency and clarity.

GRINNELL

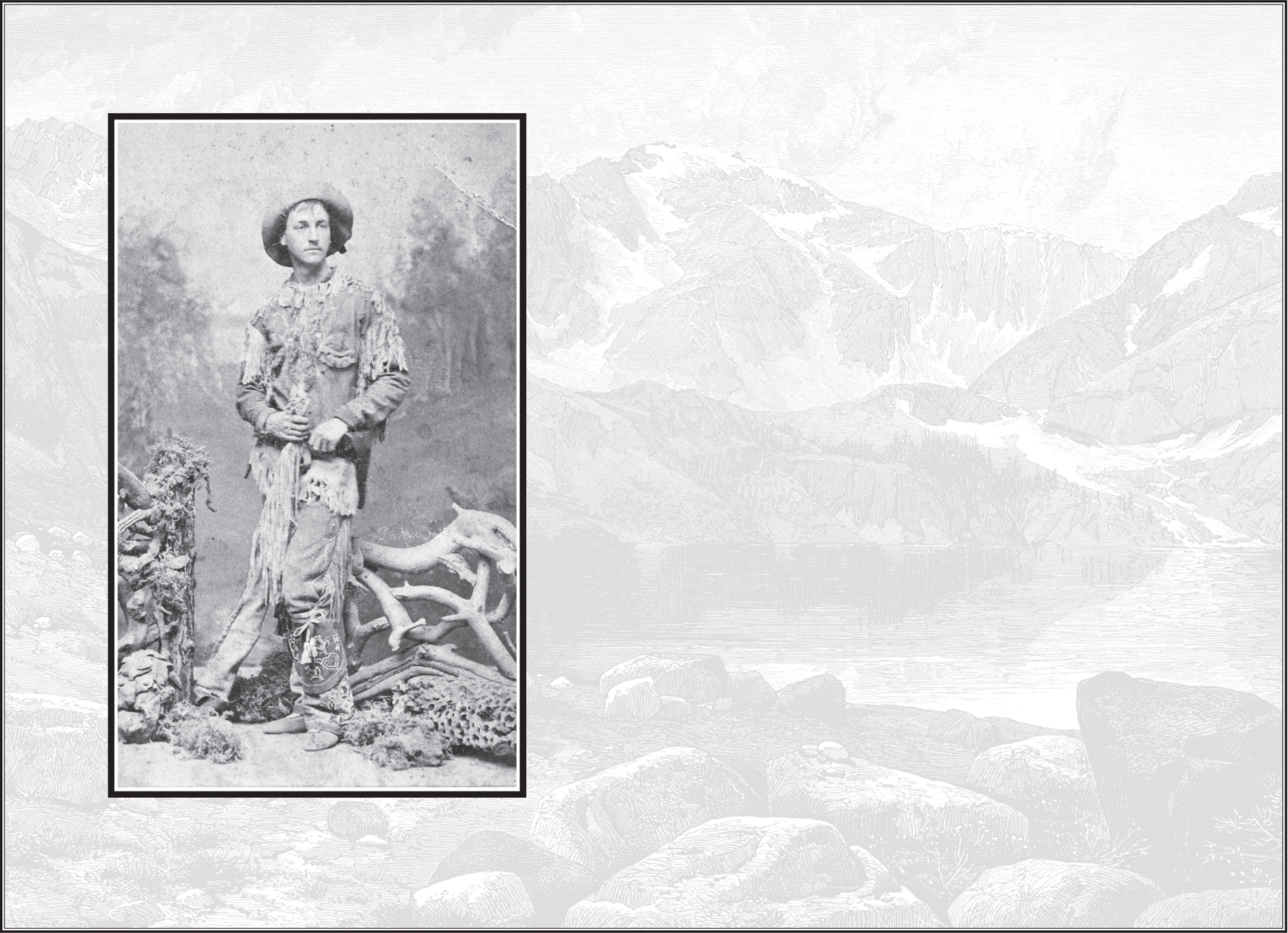

O n June 16, 1926, George Bird Grinnell departed by taxi from his townhouse on East Fifteenth Street and boarded the 20th Century Limited at Grand Central Station, heading westward, as he had done, almost annually, since his graduation from Yale more than fifty years earlier. He was seventy-six, his hair now a match for his gray eyes. For all his adventurousness as a younger man, Grinnell had become a creature of habit. His destinations, once wild and remote, were now quite familiar to him. After passing through Chicago, he nearly always stopped in Columbus, Nebraska, where the Loup River meets the Platte, to spend the night with venerable frontier scout Luther North. Their friendship, deep and unlikelygiven their differences of class and literacyhad been forged during summers of hunting and ranching together. From Nebraska, Grinnell typically headed to the Northern Cheyenne reservation on the Tongue River of southeastern Montana; to Yellowstone National Park, whose wonders first enchanted him during an expedition with army surveyors in 1875; or to the Blackfeet reservation and the magnificent mountains of what had become, largely by Grinnells efforts, Glacier National Park in northern Montana.

Grinnell knew this western country as well as almost anyone alive, and he had written prolifically on its native people, publishing benchmark books on the Cheyennes and Blackfeet, assessing their cultures, chronicling their histories, calling attention to their struggles, and advocating on their behalf. He had spent weeks at a time among these tribes, listening to their stories, observing the sun dance and other deep-rooted ceremonies, and making friends. As with Luther North, the bonds Grinnell made in the West, among both Indians and whites, were every bit as indelible as those that inter-stitched his cohort of Yale classmates.

For many years Grinnell had gone west alone, joining companions and guides once he crossed the prairies into Indian country and the Rocky Mountains. It went without saying that these outings were all male. But then in 1902, in his fifty-third year, Grinnell married Elizabeth Curtis Williams, a widow half his age, and she gamely accompanied him on many of the seasonal excursions that followed, scaling mountains and glaciers, camping in tepees, and contributing to Grinnells ethnological studies by photographing everyday life on the reservation. Indeed, it was their mutual enthusiasm for Native American culture that had first drawn the pedigreed, pipe-puffing bachelor to the proud but impecunious young woman from Saratoga County.