AMERICAS NATIONAL PARKS SERIES

Char Miller, Pomona College,

Series Editor

ADVISORY BOARD

Douglas G. Brinkley, Rice University

Patricia Limerick, Center of the American West,

University of Colorado

Robert K. Sutton, Chief Historian, National Park Service

Americas National Parks promotes the close investigation of the complex and often-contentious history of the nations many national parks, sites, and monuments. Their creation and management raises a number of critical questions from such fields as archaeology, geology and history, biology, political science, and sociology, as well as geography, literature, and aesthetics. Books in this series aim to spark public conversation about these landscapes enduring value by probing such diverse topics as ecological restoration, environmental justice, tourism and recreation, tribal relations, the production and consumption of nature, and the implications of wildland fire and wilderness protection. Even as these engaging texts cross interdisciplinary boundaries, they will also dig deeply into the local meanings embedded in individual parks, monuments, or landmarks and locate these special places within the larger context of American environmental culture.

Death Valley National Park: A History

by Hal K. Rothman and Char Miller

Grand Canyon: A History of a Natural Wonder and National Park

by Don Lago

Lake Mead National Recreation Area: A History of Americas First National Playground

by Jonathan Foster

Coronado National Memorial: A History of Montezuma Canyon and the Southern Huachucas

by Joseph P. Sanchez

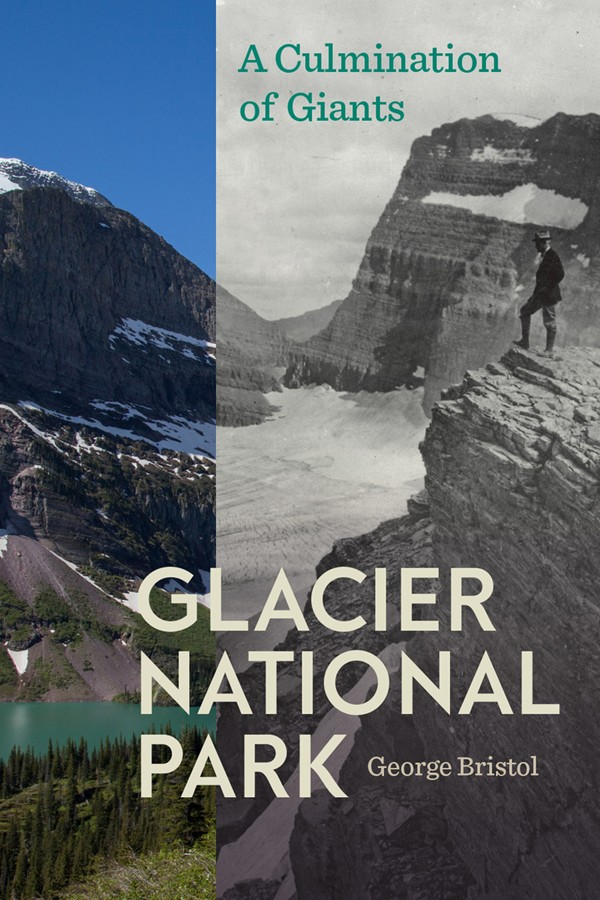

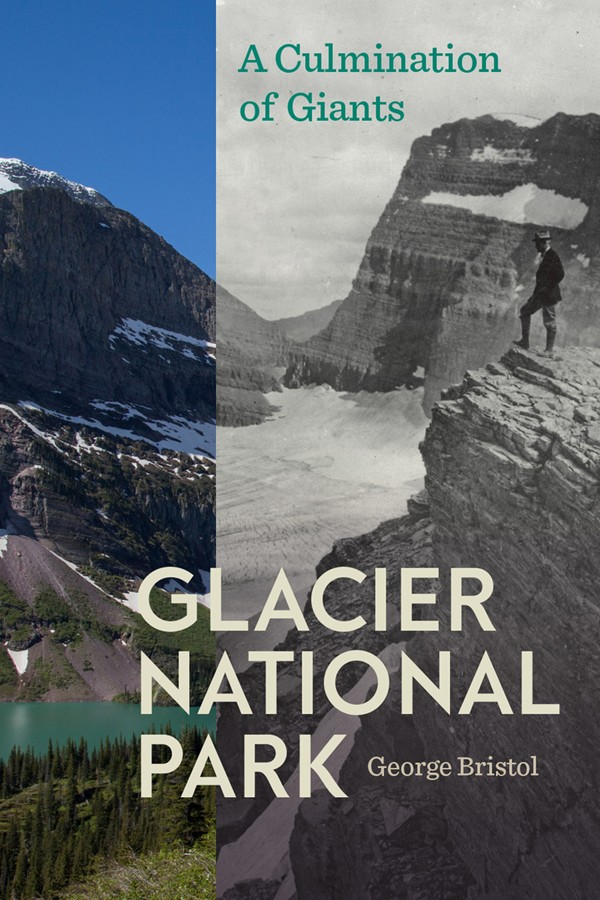

Glacier National Park: A Culmination of Giants

by George Bristol

The author and publisher extend special recognition and thanks to the Glacier National Park Conservancy for its support and financial assistance toward the development and research of this book.

The Glacier National Park Conservancy preserves the park for generations to come through philanthropic outreach, park stores, and friends from across the world. To learn more or to connect, go to www.glacier.org.

University of Nevada Press | Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

www.unpress.nevada.edu

Copyright 2017 by University of Nevada Press

All rights reserved

Cover photographs: (left) ricktravel / adobestock; (right) courtesy of Harpers Ferry Center, West Virginia

Cover design by Erin Kirk New

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Bristol, George Lambert, author. | Duncan, Dayton, co-author.

Title: Glacier National Park : a culmination of giants / George Bristol, Dayton Duncan.

Description: Reno : University of Nevada Press, 2017. | Series: Americas national parks | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017005501 (print) | LCCN 2017007380 (e-book) | ISBN 978-1-943859-48-1 (paperback : alkaline paper) | ISBN 978-0-87417-658-2 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Glacier National Park (Mont.)History.

Classification: LCC F737.G5 B73 2017 (print) | LCC F737.G5 (e-book) | DDC 978.6/52dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005501

Manufactured in the United States of America

To Nina Harrison,

who gave me food, shelter, and grand conversation

throughout a great deal of my Glacier National Park journey.

Nina passed away in October 2016.

She will brighten heaven with tales of her mountain home

and a smile that will shine all the way to Ireland.

Illustrations

Foreword

A century and a half ago, in 1868, a young man unsure of the direction of his lifehe called himself an unknown nobodywandered into the Sierra Nevada in California and found himself transfixed. John Muir, born in Scotland and raised in Wisconsin, had never seen anything quite like these western ramparts and the beautiful Yosemite Valley they surrounded, so he returned the next summer for a deeper immersion.

We are now in the mountains and they are within us, he wrote that second summer, kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us. Our flesh-and-bone tabernacle seems transparent as glass to the beauty about us, as if truly an inseparable part of it... a part of all Nature, neither old nor young, sick nor well, but immortal.

Muir would call the moment his unconditional surrender to Nature, and in that surrender, he found his lifes calling. He became Yosemites most eloquent champion, instrumental in getting it set aside as a national park. Then his devotion to Yosemite broadened to embrace other wild landscapesplaces that seemed destined for destruction in the last half of the nineteenth century in the midst of the nations headlong rush to conquer the continent. He emerged as a leader of the budding conservation movement, awakening his adopted country to the understanding that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.

Muirs writings brought public attention to Alaskas Glacier Bay, Arizonas Grand Canyon and Petrified Forest, Californias Sequoia and Kings Canyon, Washingtons Mount Rainier, and other majestic landscapes that would soon find protection as national parks. He helped found the Sierra Club. And he would use his fame and persuasive powers in the realm of politics, including a remarkable three-day camping trip in Yosemite with President Theodore Roosevelt in which the two menso different in many respects, but so united in their love of the outdoorsbonded over their nightly campfires and pointed the United States on a new course for conservation for the twentieth century.

Given the breadth of Muirs impact, its easy to forget that it all started when a young unknown nobody from the flatlands entered the Sierra, fell in love with the mountains, and, in that transcendent moment, decided to do everything in his power to encourage others to do the same. The place had connected him with something much bigger than himself; then he, in fact, became bigger.

In that, John Muirs story, remarkable and profoundly consequential as it is, in actuality is merely one story among many others in the long history of our national parks. Look into the background of virtually any national parkhow it came to be set aside or how it continues to be protectedand what you invariably discover is one persons (or a small group of peoples) affection for a particular place, an affection so deep, so transformative that they devote themselves to making sure that other people, people they will never meet and in generations they will never know, will have the opportunity to fall in love with it just as they did. Its always personal. Its always inspiring. And, I might add, it always requires hard work, persistence, and complete dedication.

So it is with my friend George Bristol. Nearly a century after young John Muir entered Yosemite and found his destiny, Bristol boarded a train in Texas in 1961 at age 21 and ended up in northwestern Montana to take a summer job at Glacier National Park. Imagine a kid from Austin stepping off that train and experiencing his first mountains (and what magnificent mountains they are!), his first view of snow in midsummer, his first scent of pines, his first alpine waterfalls, his first look at a trout leaping in the eddy of a cascading mountain river. I thought Glacier was the most beautiful place on Earth, he said. I still do.