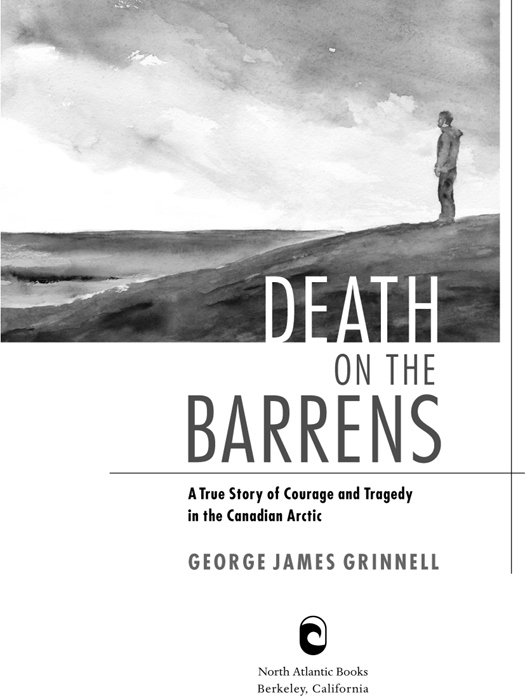

This book is dedicated to the memory of my father,

George Morton Grinnell (19021953),

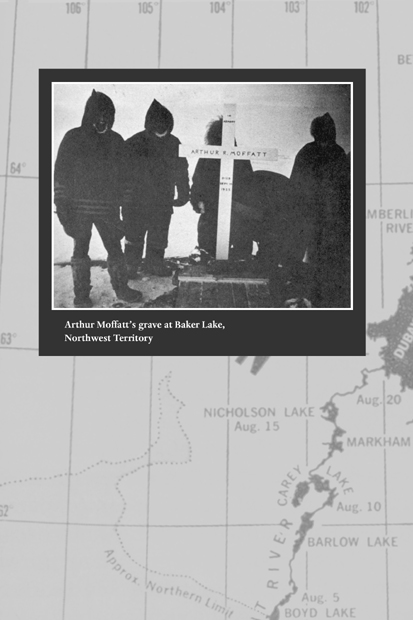

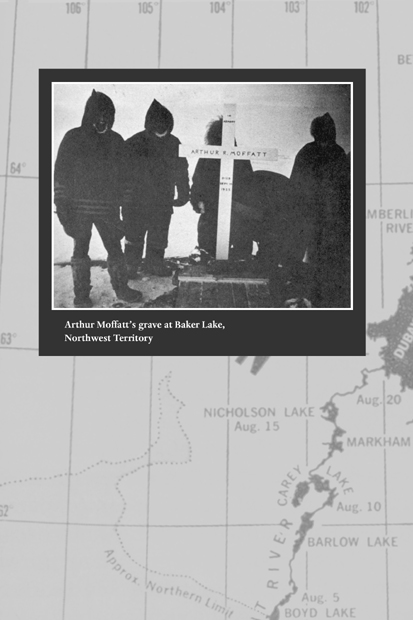

to the memory of the leader of the expedition

across the Barren Grounds of Keewatin,

Arthur Moffatt (19191955),

and to the memory of Sandy Host (19541984),

Betty Emer (19611984),

George Landon Grinnell (19621984),

and Andrew Preble Grinnell (19681984),

who died together on the barren coast of James Bay.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

PART II

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

PART III

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

PROLOGUE

The circumstances leading up to Arthur Moffatts death on the Barrens were first described by Skip Pessl, the second-in-command of the expedition, on the television program Bold Journey in 1955.

At about the same time, Skips bowman, Bruce LeFavour, told his interpretation of events in the local newspaper of Amsterdam, New York.

Three years after Arts death, Sports Illustrated published Arts diary with a commentary by Arts bowman, Joe Lanouette.

Over the last fifty years, wilderness canoeists have concluded that Art made every mistake in the book, but a Buddhist monk, Kama Ananda, told me he was of a different opinion.

The purpose of art is to unite the particular with the universal, to elevate the sordid into the sublime, and to bathe the tragic in an ocean of compassion.

INTRODUCTION

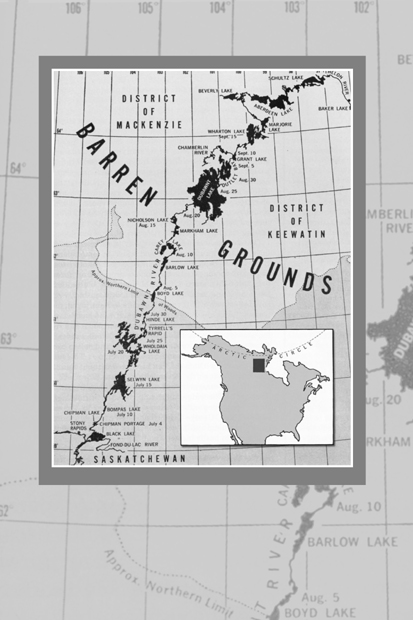

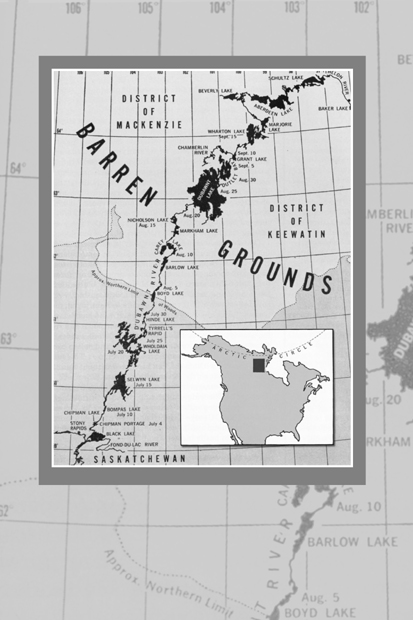

On September 14, 1955, Arthur Moffatt, an experienced wilderness canoeist, died from exposure on the banks of the Dubawnt River, deep in the heart of the Barren Grounds of northern Canada. He was thirty-six. The five younger companions with him just barely survived.

The result of fifty years of reflection, guilt, and gestation, this book represents the personal story of that unusual wilderness sojourn and that horrific day by one of its survivors. Intertwined and juxtaposed, it is also a tale of George Grinnells travels through life. Both tales are unconventional and fascinating.

The 1955 canoe story can be viewed from either of two extreme perspectives. The first view is the practical and dismissive observation that as a remote sub-Arctic canoe expedition, it was poorly planned and irresponsibly executed, and its tragic conclusion was a natural consequence of that folly. It is, however, a truthful story about a real canoe trip, with all its associated petty human interactions and problems. Many of the trips problems arise from the gnawing reality of incessant hunger resulting from an inadequate daily food ration.

The second view takes a much deeper look at this story. Most individuals who have traveled in the Barrens have been affected by them in some spiritual manner. My own first canoe venture into the Barrens was also on the Dubawnt. That was 1969, and due to the late ice that year and similar food shortages, it was a hard trip. But it affected me deeply, and I have returned five times since then to do similar crossings of the Barrens in the same area in an attempt to recapture that same spiritual experience. It is precisely this vivid spiritual experience that permeates Georges narrative and makes it a joy to read.

In the words of the author, The real voyage is traveled within ones soul. And as a spiritual odyssey Georges adventure was a truly extraordinary passage.

The majority of us live our lives in relative psychological security, choosing to graze in the center of the pastures of the human asylum. We leave it to genuine artists and individuals, like George Grinnell, to explore the unseen and less-traveled edges of our enclosure for us. This exploration of the human soul is far more difficult than any exploration of the geographical landscape can possibly be. It is both difficult to arrive at the edge, the place of enlightenment, of heightened sensation and perception, and then equally difficult to return and to reattach to the humdrum everyday world of the center.

Their three-month canoe trip across the uninhabited Barrens takes George Grinnell to the lip of the abyss that separates sanity from insanity and life from death. And it is his firsthand exploration of this uncertain edge that provides the profound insights that make this a most powerful and unique narrative.

To illustrate with just one such exploration in Death on the Barrens, in Chapter Sixteen the author describes his experience of a temporary loss of identity and the associated panic attack. He was in terror that his soul was being vaporized by the wildernessby an overwhelming wilderness that lives forever and cares not a whit about a human individual. The nothingness of the barren-land wilderness was almost too much for the youthful psyche to bear.

Edward McCourt, in his book The Yukon and the Northwest Territories, asks the rhetorical question, Why do men go to the Barren Lands?

In an eloquent passage, a portion of which follows, he answers, The Barren Grounds is a world so vast, so old, so remote from common experience as to encourage the annihilation of self; its sheer immensity reduces the individual by comparison to a bubble on the surface of a great river, a foam-fleck on the ocean; and its great ageits rocks are the oldest in the worldshrinks his life span to immeasurable minuteness. It is a world that affords so little evidence of mans existence that it tends to suspend the passions we associate most commonly with himlove, hate, pride, fear. And in the long run it makes what a man does or does not do seem of little moment, even to himself. It is a world that by reason of its seeming invulnerability challenges the brash, optimistic young to attempt great things and assures the old that what they have failed to do makes no difference.

G EORGE L USTE

F OUNDER OF THE W ILDERNESS C ANOE S YMPOSIUM

CHAPTER 1

The Mounties

Illusion is so beautiful. And Truth can make you cry.

M ICHAEL E LLWOOD

Before our food arrived that afternoon, we four divided up the sugar bowl between us and drank the contents of the cream pitcher. The following morning, the manager of the one hotel in Churchill, Manitoba, told us the Mounties wanted to see us. As we walked up the frozen dirt street to the headquarters of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, snow swirled about in the wind. I saw a crust of bread in the dirt and reached for it, as did the others. We laughed at our good fortune. Our bellies were full now, full to the point of bursting, but the sensation of being hungry had not left, and we could not stop eating or saving food. To be on the safe side, I put the crust in my pocket even though my companions and I had already filled our hotel rooms with food.