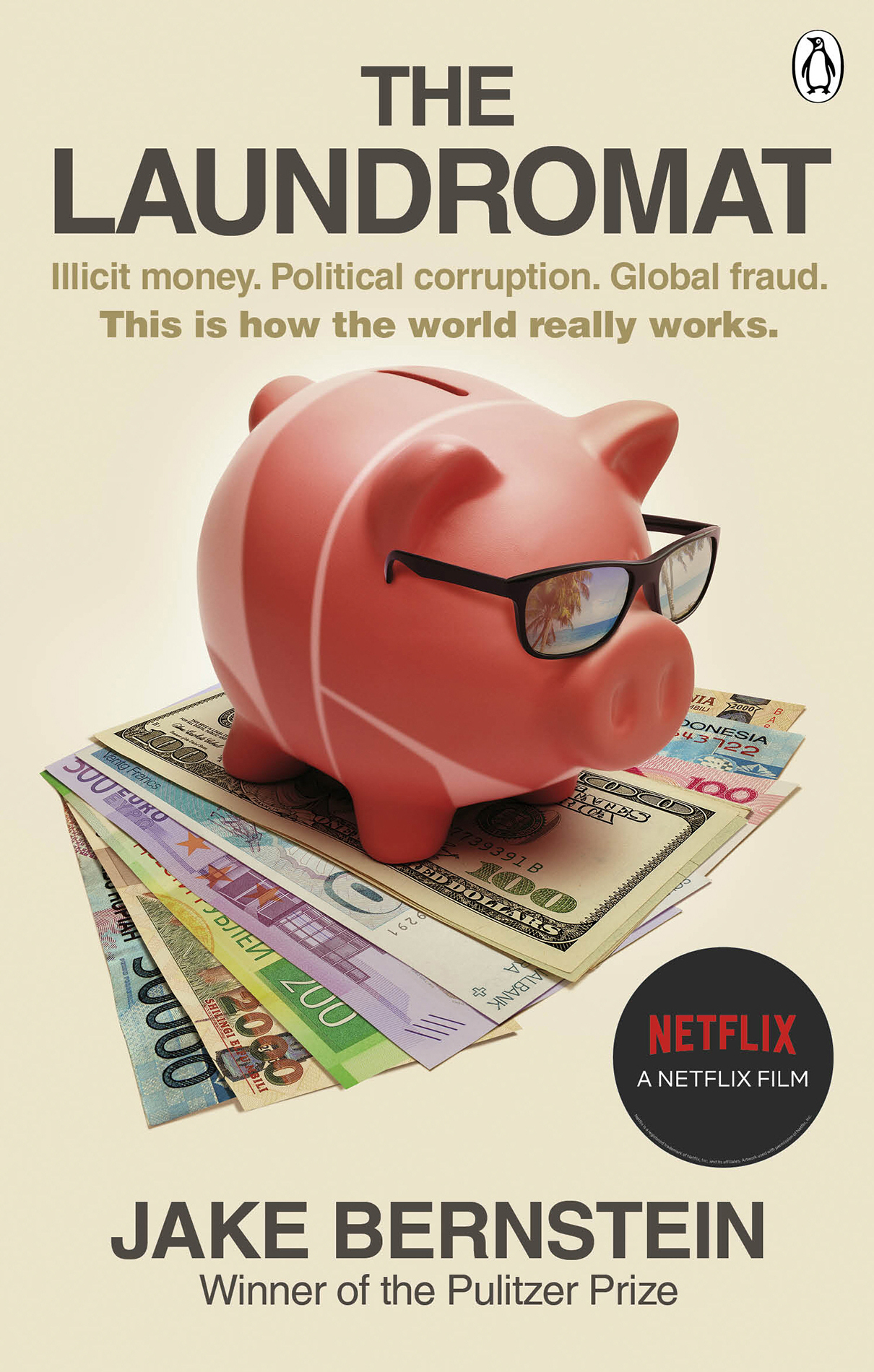

Jake Bernstein

THE LAUNDROMAT

Inside the Panama Papers

Investigation of Illicit Money

Networks and the Global Elite

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jake Bernstein was a senior reporter on the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists team that broke the Panama Papers story. In 2017, the project won the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. Bernstein earned his first Pulitzer Prize in 2011 for National Reporting, for coverage of the financial crisis. He has written for The Washington Post, Bloomberg, The Guardian, ProPublica, and Vice, and has appeared on the BBC, NBC, CNN, PBS, and NPR. He was the editor of The Texas Observer and is the coauthor of Vice: Dick Cheney and the Hijacking of the American Presidency.

ALSO BY JAKE BERNSTEIN

Vice: Dick Cheney and the Hijacking of the American Presidency

(with Lou Dubose)

To Eve, without whom this book would not exist.

Your wisdom and beauty light my day.

PROLOGUE

In the spring of 2015, a prosperous shipping-company executive in Mexico faced a problem. He wanted to buy a $585,000 town house in Seattle for his sister and ten-year-old niece. It was not the distance that posed a challenge. His sister was embroiled in a divorce. The executive did not want the house to become part of the dispute. He also hoped to minimize any taxes on the transaction. Finally, the ownership of the house needed to revert back to him should his sister die.

He contacted a law firm in Panama that handled such matters. The firm had decades of experience helping people all over the world hide their money and disguise their most intimate affairs. Mostly it sold anonymous shell companies based in tax havens. Sometimes, as in this case, it went a bit further.

The executive flew to Panama. A car picked him up at the airport and took him to the firms offices. Nothing about the firms outward appearance indicated it was a massive global operation with hundreds of employees scattered throughout the world. Its headquarters was in a squat office building on an unassuming mixed residential and commercial side street in Panama City. The firm owned many of the houses on the street, but that was not immediately obvious.

The new client met with one of the firms top lawyers and explained what he hoped to accomplish. The lawyer asked for and received proper documentation from the client that established his identity, including copies of his passport and bank statements. The scheme the lawyer devised was not particularly complex by the standards of a wealth management industry that is accustomed to mixing and matching multiple legal structures and countries to safeguard the riches of its clients. This transaction was a small one. Of questionable ethics, but by all appearances completely legal.

The strategy began with a Delaware limited liability company. It would be the entity to buy the house. The law firm contacted an outfit in Delaware that procured companies in the state on its behalf. To establish a company based in Delaware required minimal information. Anyone, anywhere in the world, could create one. As long as the company did no business in Delaware, it was not required to file any information about its activities or reveal who really owned it. The company only had to list a member, but that could be another company or legal entity.

The ability of foreigners to hide their activities through companies in Delaware and other states was the cause of considerable consternation by governments around the world, including the United States. The same year the Mexican businessman set up his company, the U.S. Treasury issued a report in which it expressed particular concern about Eurasian organized crime figures using U.S. shell companies to conduct their illegal activities.

The executive had a name in mind for his company. He wanted to call it The Cherry Group, but a Delaware company with that name already existed. He settled for Cherry Group USA LLC. The company cost little more than $300 to summon into existence but the law firm charged $1,260 in total to make it active with all the appropriate books and records. The executive paid promptly.

But the Delaware company by itself was not sufficient for the executives needs. If he owned it directly, it would be clear to the soon-to-be ex-husband and the U.S. government who actually purchased the house. The lawyer suggested a Panamanian foundation that would legally own the Delaware company.

The law firm gave the executive a choice of names for the foundation, Vanora or Eleus. It had already created the foundations two months earlier, before the firm was even aware of this particular client. Two women, who were actually low-paid employees of the firm, ostensibly controlled the foundations. In actuality they served as figureheads for thousands of companies and foundations. Their existence was a shield behind which the actual owner could hide. The executive chose Vanora and paid $3,950 to buy the foundation.

By this time, a lawyer from another firm in the United States had also been brought in to help shepherd the transaction. His retainer was $3,500. The executive made plans to fly to Seattle to buy the house. But his real estate broker informed him of a hitch: He could not purchase the home in the name of Cherry Group USA because the company was owned by the foundation, not him. This was easily remedied. The two low-paid employees of the Panamanian law firm simply signed a document saying that as the controlling members of Vanora Foundation, they authorized him to buy the house. The law firm was willing to provide this service because the executive was paying for the house in cash, so there was no risk the Panamanians would be stuck with the mortgage.

This was only one of thousands of transactions the law firm facilitated in 2015. Its name was Mossack Fonseca. Unbeknownst to the firm, at the same time it was helping someone secretly buy a house in Seattle, its data was being siphoned off and given to reporters. The resulting global journalism investigation, the Panama Papers, afforded an unprecedented look into the operations of an underground economy through which trillions of dollars flow annually.

This river of cash exists in a largely unregulated place known as the secrecy world. Its an alternate reality available only to those who can afford the trip. In the secrecy world, wealth is largely untouchable by government tax authorities and hidden from the view of criminal investigators. Through the secrecy world, family dynasties are nurtured, their fortunesoften acquired illicitlylaundered and passed on to heirs. Its a place where capital always triumphs over labor and the well-to-do are free to ignore the laws that govern their fellow citizens.

Global private wealth has steadily increased in recent years, from $121.8 trillion in 2010 to $166.5 trillion in 2016. But for those in the top 0.01 percenteach of whom had more than $40 million in assetsa staggering 30 percent stiffed the taxman. Not surprisingly, the ease by which wealth is transferred through the secrecy world has become a major contributor to global inequality.

Next page