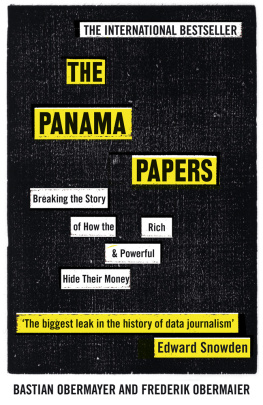

The biggest leak in the history of data journalism Edward Snowden

The inside story from the journalists

who set the investigation in motion.

Late one evening, investigative journalist Bastian Obermayer receives an anonymous message offering him access to secret data. Through encrypted channels, he then receives documents showing a mysterious bank transfer for $500 million in gold. This is just the beginning.

Obermayer and fellow Sddeutsche Zeitung journalist Frederik Obermaier find themselves immersed in a secret world where complex networks of shell companies help to hide those who dont want to be found. Faced with the largest data leak in history, they activate an international network of journalists to follow every possible line of enquiry. Operating for over a year in the strictest secrecy, they uncover a global elite living by a different set of rules: prime ministers, dictators, oligarchs, princelings, sports officials, big banks, arms smugglers, mafiosi, diamond miners, art dealers and celebrities. The real-life thriller behind the story of the century, The Panama Papers is an intense, unputdownable account that blows their secret world wide open.

Contents

Foreword

There are moments in history when a big truth is suddenly revealed. In 2010 leaked US diplomatic cables showed the White Houses private thinking about its friends and enemies. Three years later a contractor working for the National Security Agency exposed how the US and the UK are secretly spying on their own citizens.

His name was Edward Snowden. We learned that spooks from Britains listening station GCHQ could if they wanted bug your iPhone. Or remotely activate your laptop web camera. Snowdens revelations caused outrage and started a global conversation about the boundaries of privacy in a digital age. Except in Britain, land of James Bond, where many met his revelations with a complacent shrug.

In April 2016 something else hidden in plain sight was exposed. Namely that the secret offshore industry centred in tax havens like the British Virgin Islands was not, as had been previously thought, a minor part of our economic system. Rather it was the system. Those who dutifully paid their taxes were, in fact, dupes. The rich, it turned out, had exited from the messy business of tax long ago.

The journalists who unearthed this bitter truth were Bastian Obermayer and Frederik Obermaier of Germanys Sddeutsche Zeitung . (They are not related but their German and international colleagues fondly nickname them the Brothers Obermay/ier.) The paper, based in Munich, has an excellent track record of working on difficult and important investigations.

Reporters often get offered information, stuff. Generally, it turns out to be disappointing. As Obermayer recounts, in early 2015, late one evening, he received an anonymous message. It said: Hello. This is John doe. Interested in data? Obermayer replied: Were very interested, of course.

The data turned out to be bigger than anyone might have imagined. The source his or her identity remains unknown had got hold of the entire internal database of a major Panamanian law firm. The firms name was Mossack Fonseca. It specialized in setting up anonymous offshore shell companies.

The motivation here was simple. Like Snowden, the source wanted to expose criminal wrongdoing among the firms shadowy clients. The leak was an act of bravery. It eventually amounted to 11.5 million documents, delivered in real-time instalments. It was the biggest leak ever, and far larger than the top-secret Snowden Files or US State Department cables.

It included the records of 214,000 offshore companies, names of real or beneficial owners, and passport scans. There were bank statements. And email chains. Often these were between Mossack Fonsecas head office in Panama and intermediaries, typically other lawyers, accountants and banks. And from the firms branches in UK crown dependencies like Jersey or the Isle of Man.

What followed was a thrilling and secret year-long journalistic collaboration across more than eighty countries. The Sddeutsche Zeitung shared its material with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the ICIJ, which is based in Washington DC. The ICIJ in turn gave access to the data to 100 media organizations across the planet. In Britain that was my newspaper, the Guardian , and the BBC.

The journalists gave the leaked files a name. They were the Panama Papers. The name was a conscious echo of the Pentagon Papers: volumes of secret documents leaked in 1971 by Daniel Ellsberg that lifted the lid on the US war in Vietnam.

I found myself back in the Guardian s investigations bunker. Actually, it had a bucolic view of Regents Canal in London: houseboats, joggers, coots. In 2013 Id been part of a small group that had studied the Snowden Files here. This project was different. Via a secure platform, called the iHub, journalists were encouraged not to compete with each other but to share information actively and to swap leads and tips. We did, in a flurry of encrypted emails.

For some time the global media industry has been in a state of gloom. Newsrooms are downsizing; the ad market has collapsed. Suddenly, though, this counter-intuitive model of cooperation looked like the way to go at a time when media organizations were broke. Paradoxically, it felt to us like a golden age for investigative journalism. The leaks kept coming. And grew bigger: in this case, an astonishing 2.6 terabytes.

But would anyone care? By 2016 almost 400 journalists were working secretly on the story, with an agreed publication date of 3 April. Clandestine group meetings had taken place in Washington, Munich and London. There were two concerns. One, that the leak might itself leak that someone would accidentally bust the embargo. The other was that the public would respond to the Panama Papers with an indifferent yawn.

We neednt have worried. In Iceland the prime minister resigned. In Argentina there were demonstrations. In Azerbaijan a small war was initiated so some believed to distract from revelations featuring the president and his daughters. In China censors blocked the words Panama Papers and jammed the website of the Guardian. In Russia aides to Vladimir Putin fumed about a Western spy conspiracy.

In Britain, meanwhile, David Cameron experienced the worst week of his premiership. The Panama Papers revealed that the offshore fund run by Camerons late father Ian had paid no British tax. For three decades. The fund, Blairmore Holdings Inc, had gone to absurd lengths to pretend it was based in the Bahamas. It hired a small army of Bahamas residents to sign paperwork, including a part-time bishop.

Downing Street refused to answer questions about Camerons tax affairs, saying they were a private matter. Eventually Cameron came clean: hed owned shares in Dads tax haven fund. He sold them for 31,500 just before becoming prime minister in 2010. Cameron was reluctant to acknowledge what was obvious: that his familys fortune legally of course came from privileged offshore wealth.

Its too early to say whether the Panama Papers will usher in a new era of transparency. The G20 has promised to act. Cameron, George Osborne and Jeremy Corbyn all published their tax returns a start. But as US president Barack Obama noted, tax avoidance is a huge global problem. Its made worse, Obama said correctly, by the fact that using offshore structures is perfectly legal.

Still, the past few months have seen a victory of sorts for those of us, the little people, who do pay our taxes. From now on, the super-rich and other characters who use exotic offshore structures will be a nervous bunch. How long, they must be wondering, before the next leak?

Next page