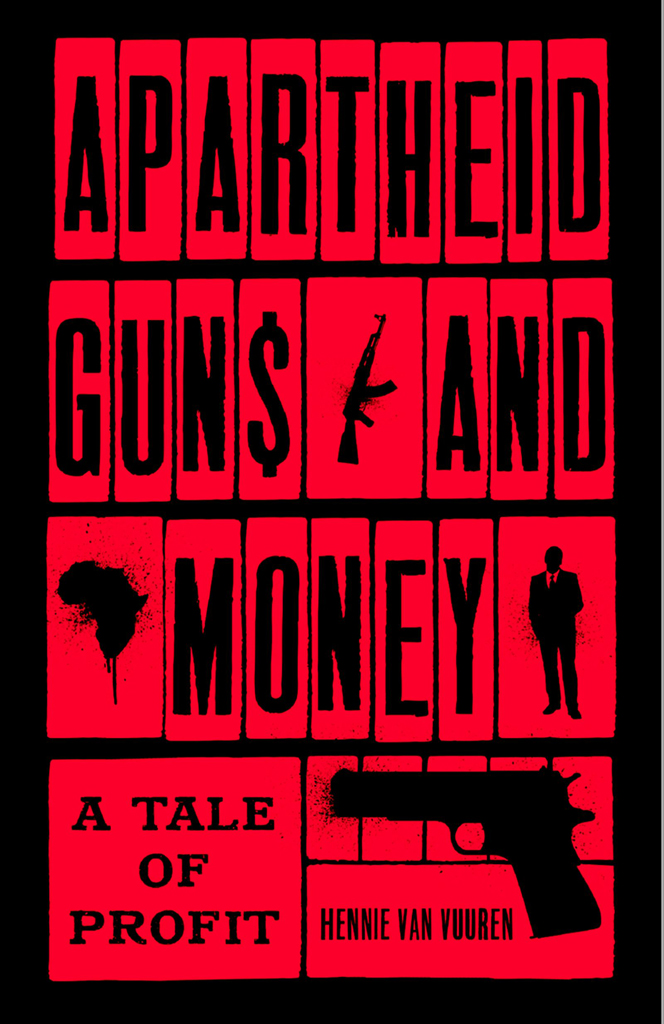

APARTHEID GUNS AND MONEY

Apartheid Guns and Money

A tale of profit

Hennie van Vuuren

RESEARCH

Michael Marchant

with

Anine Kriegler & Murray Hunter

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

41 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3PL

Hennie van Vuuren, 2018

All rights reserved.

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

The right of Hennie van Vuuren to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78738-247-3

www.hurstpublishers.com

Dedicated to friends and comrades who, in seeking justice, demand the right to know, live to tell the truth and love unconditionally

You follow drugs, you get drug addicts and drug dealers.

But you start to follow the money, and you dont know where the fuck its gonna take you.

DETECTIVE LESTER FREAMON, THE WIRE, SEASON 1

This book is intended to be in the public interest. The public has a right to know. It is based on a vast body of information collected from numerous sources. These include archival records, declassified documents, academic literature such as books, and newspaper articles. Interviews with sources, both named and those who didnt want to reveal their identity, provide eye witness accounts. In addition, material was provided to me from confidential sources. I have endeavoured to verify information to the extent possible.

Subsequent to publication of this book, Open Secrets together with the South African History Archive will make available source documents for public scrutiny.

Contents

We are the liquidators of this firm, the state president is reported to have said to one of his ministers in December 1989. The two men stood on the stoep of the presidential home outside Durban overlooking the Indian Ocean. The humid air was almost certainly heavy with the smell of expensive liquor and acrid cigarette smoke. The Berlin Wall had fallen a month prior and the tide of politics seemed to be turning across the globe. FW de Klerk, the newly elected state president and leader of the National Party (NP), was the CEO of a regime at war with its people and running out of time. The death squads prowling the streets and the nuclear warheads in its bunker could hold the line, but for how much longer? A decade, perhaps; maybe two.

Three years later the trucks grumbled to a halt at a factory outside Pretoria. The final act of liquidation was about to begin. A former intelligence officer reports that after the shredders stopped working, millions of documents containing the intimate details of agents and citizens alike were torn up by hand, packed into standard, black refuse bags and fed to the roaring flames.

With this, the written record of countless acts of individual culpability were destroyed. The memory of iniquity, injustice and oppression could not be erased as easily. It remains with those who carry that burden, physically, emotionally and materially. But could the last all-white government, through this final act of vengeance and self-preservation, leave enough blank spaces in history that future generations would forever fail to tell this countrys story? Will this act condemn South Africans who outlived this regime to repeat its wicked ways?

There is little evidence to suggest that South Africa today, while still struggling to achieve the democratic heights envisioned by activists past and present, is threatened by a reintroduction of the system of apartheid. However, shades of that system, which continue to this day, do threaten our freedom. Inequality, poverty, insecurity, state surveillance, excessive police force, selective prosecutions and threats to media freedom form a good part of the post-apartheid political experience. Such practices strike a chord of anger among ordinary people precisely because this is familiar terrain. South Africans have good reason to demand that elites take their finger off the repeat button, not only because our Constitution is explicit about what our rights are, but because it is aspirational in how these rights should be advanced to the benefit of all.

An outlier in our understanding of apartheid practice has been the issue of corruption and economic crime in the post-apartheid period. It did not start to manifest the day that the Mandela administration was inaugurated. Our conception of South Africa as a new nation was a helpful tool to build national unity at a key moment, but it has also meant that we have denied uncomfortable truths. When Nelson Mandela was elected president, his government had to craft a new administration from disparate authorities in former white-administered provinces and ethnic black homelands alike. He had to deal with the internal contradictions of a liberation movement that was home to all and inevitably counted crooks and opportunists among its ranks. Added to this was the existence of a powerful private sector, dominated by white business interests, that had a habit of betting on the short term.

The democratic elections in 1994 and the finalisation of the Constitution two years later signalled a commitment to integrity and to the creation of public institutions that sought to uphold these principles. With this, a message was sent that corruption at all levels would not be tolerated. But this important process had a caveat: corruption and economic crime in the past would be left to lie, like fat, rich sleeping dogs. To have looked backwards and prosecuted past crimes at that exact moment could have wrecked the peace-making process. The reason was the scope and scale of economic crimes. Thorough investigation would have touched powerful interest groups across the globe: bankers, arms dealers, political parties, foreign leaders, arms companies, oil traders, lobbyists, foreign intelligence agencies and the domestic military. They were all implicated in a largely criminal economy that was thought best left buried even if we recognise, in hindsight, that this was folly.

The apartheid economy had, in the preceding 15 years, built a massive infrastructure to bust international sanctions. With the help of friends across the globe who smelt profit, a criminal economy was put in place to sustain white power. A highly secretive machinery was created to corrupt politicians, launder public and private funds, and break international sanctions. This effectively criminalised key institutions within the public and private sector. And it relied extensively on the support of right-wing business, political and intelligence networks across the globe.

This pervasive international system a war machine, as I describe it remains a largely hidden aspect of our past, and it is this that I attempt to piece together in this book. So, too, does the identity of the multitude of individuals who created and ran it. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the war machine was an essential element of the survival of PW Bothas government and the political fortunes of his ministers such as De Klerk. The machinery funded war and violence in South Africa and elsewhere. NP politicians and their allies in business became enmeshed in a sinister world governed by the interests of right-wing forces, neoconservatives and anti-democratic regimes. Even the South African parliament, which existed for minorities only, was largely blind to the extent of these endeavours. These were deep state networks that operated outside the law in South Africa and other countries. Gallingly, as we will see repeatedly through this book, many of the countries that aided and abetted apartheid had officially supported sanctions against South Africas racist regime and, in certain instances, openly funded the liberation movements.