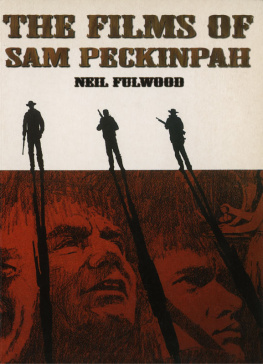

Neil Fulwood - One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema

Here you can read online Neil Fulwood - One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, publisher: Pavilion Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema

- Author:

- Publisher:Pavilion Books

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

About Batsford

Founded in 1843, Batsford is an imprint with an illustrious heritage that has built a tradition of excellence over the last 168 years. Batsford has developed an enviable reputation in the areas of fashion and design, embroidery and textiles, chess, heritage, horticulture and architecture.

For Paul Rowe

AUTHORS NOTE

This book focuses on scenes from 100 films that have had an effect on sexual representation in cinema. In order to provide context, it has been necessary to mention a number of other films. Therefore, the 100 films under specific discussion are identified in the text in boldface.

All stills courtesy of The Joel Finler Picture Collection, except for those on pages 11 and 13, which are from the authors own collection.

First published as an eBook in 2014 by

Batsford

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Limited

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

www.batsford.com

Copyright Batsford 2014

Text Neil Fulwood 2003

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, displayed, extracted, reproduced, utilised, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise including but not limited to photocopying, recording, or scanning without the prior written permission of the Pavilion Books Company Limited.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84994-255-3

Paperback ISBN: 978-0713488586

CONTENTS

implicit

CHAPTER ONE

P icture the setting, not that its particularly romantic or erotic: a run-down diner/gas station somewhere in the sticks, a sign out front reading MAN WANTED. The proprietor is a shambolic middle-aged drunkard; the business is starved of customers. Into this milieu comes Frank Chambers (John Garfield), a drifter and self-confessed cheap nobody; so begins The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946). He enters into dialogue with the proprietor, Nick Smith (Cecil Kellaway), who offers him a job and a hamburger on the house. They go inside to discuss terms and conditions. Nick leaves Frank to tend to the stove while he goes to serve someone waiting for petrol on the forecourt.

Across the floor, bare of carpeting, rolls a tube of lipstick. It comes to rest at Franks feet. The camera tracks back, reaching an open door, which frames a tanned and shapely pair of legs. A quick pan up and we are presented with an archetypal film noir scenario: the introduction of the femme fatale; the promise of the erotic; the moment where the heros fate is sealed.

Not that Frank is much of a hero. Nor is film noir a genre in which heroes are prevalent. Indeed, the usual motivations of film noir characters are greed, lust or fear. The men, for all their tendencies towards violence, are often weak; they allow themselves to be manipulated by women. That the femmes fatales are the stronger characters owes in no small part to their use of sexual self-awareness as their weapon of choice.

The femme fatale here is Cora Smith (Lana Turner), wife of the hapless Nick, and sole beneficiary under the terms of his will. As the film progresses, she will inveigle Franks help in murdering him, the quicker to acquire his business and profit from his life insurance policy. And from the outset, it is evident that Frank is going to do her bidding. His first interaction with Cora completely non-verbal tells us all we need to know. She stands framed in the doorway, watching him coolly. Her outfit a revealing top and shorts, almost as if she were dressed for the beach is as white as her motives are dark. Frank picks up the tube of lipstick and hands it to her. She glosses her lips right in front of him, still eyeing him insouciantly, then turns away. The hamburger burns on the stove as he gawps after her.

Archetypal film noir: John Garfield ensnared by Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Not only is the scene loaded with unspoken tension between the characters; it also acts as a metaphor for the film entire. The tube of lipstick equates to the favours Cora will bestow on Frank should he do her bidding; the area of floor it rolls across represents the property Cora schemes to get her hands on; and the conflagration on the stove symbolizes (albeit unsubtly) the heat of their passion and the violent act that will ultimately destroy them.

The promise of the erotic: suggestion and manipulation in film noir

Billy Wilders Double Indemnity (1944) is very much the precursor of The Postman Always Rings Twice unsurprisingly, since both were based on novels by James M Cain. Again a culpable male, insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), is beguiled by a predatory female, Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), intent on reaping the rewards of her husbands premature demise. In a plot twist more coldly cynical than anything Postman has to offer, Neff is made complicit even before the murder when Phyllis persuades him to take out the policy (the films title derives from the accidental death clause) without her husbands knowledge.

Like Cora, she uses Neffs attraction to her in order to manipulate him. But whereas Coras ploys are entirely physical (she is constantly applying lip gloss, smoking cigarettes in a manner that draws attention to her lips or flouncing around in beach wear), with Phyllis, notwithstanding that she is introduced wearing just a towel, there is a more intellectual edge. Whereas Cora leads her accomplice on, Phyllis sounds him out. Neff meets Phyllis when he arrives at her house to discuss car insurance with her husband. The husband is conveniently out. Phyllis appears at the top of the stairs, betowelled. During the course of the scene, they twice base their conversation around metaphors. The first plays on Neffs line of work.

Neff: Id hate to think of you getting a scratched fender when youre not covered.

Phyllis: I know what you mean. Ive been sunbathing.

Neff: Hope there werent any pigeons around.

The erotic connotations of not covered (unclothed) are reinforced by Phyllis choosing this moment to withdraw to her room to change. She reappears, still buttoning up her dress, and slowly descends the stairs. The camera lingers on her ankle-bracelet (traditionally a piece of jewellery associated with prostitution). The implication of voyeurism in Neffs comment about pigeons is here made manifest.

Their second bout of metaphor-laden verbal sparring comes when Neff makes it clear that he has less interest in returning later to speak with her husband, and more in actually seeing her again. Phyllis castigates him for going too fast (i.e. being too insistent).

Phyllis: Theres a speed limit in this state. 45 miles an hour.

Neff: How fast was I going, officer?

Phyllis: Id say about 90.

Neff: Suppose you get down off that motorcycle and give me a ticket.

Phyllis: Suppose I give you a warning instead.

Neff: Suppose it doesnt take.

Phyllis: Suppose I have to rap you over the knuckles.

Neff: Suppose I burst out crying and put my head on your shoulder.

Phyllis: Suppose you put it on my husbands shoulder.

Suggestive stuff. The main implication is that Neff already sees himself as subservient to her. Also, the choice of a legal infraction (albeit a minor one) as metaphor tells us they will soon be partners in crime. But most of all, there is the sense of Phyllis working out an angle how she can use Neff to her best advantage even as she weaves her seductive web.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema»

Look at similar books to One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book One Hundred Sex Scenes That Changed Cinema and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.