Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

HOLLYWOODS ARTISTS

Film and Culture

FILM AND CULTURE

A series of Columbia University Press

Edited by John Belton

For a complete list of titles, see .

Hollywoods Artists

The Directors Guild of America and the Construction of Authorship

Virginia Wright Wexman

Columbia University PressNew York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55143-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wexman, Virginia Wright, author.

Title: Hollywoods artists : the Directors Guild of America and the construction of authorship / Virginia Wright Wexman.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2020] | Series: Film and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052936 (print) | LCCN 2019052937 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231195683 (cloth) | ISBN 9780231195690 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Directors Guild of AmericaHistory. | Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesHistory. | Motion picturesProduction and direction United StatesHistory. | Motion picture industryUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.P7 W477 2020 (print) | LCC PN1995.9.P7 (ebook) | DDC 791.4302/330922dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052936

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052937

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

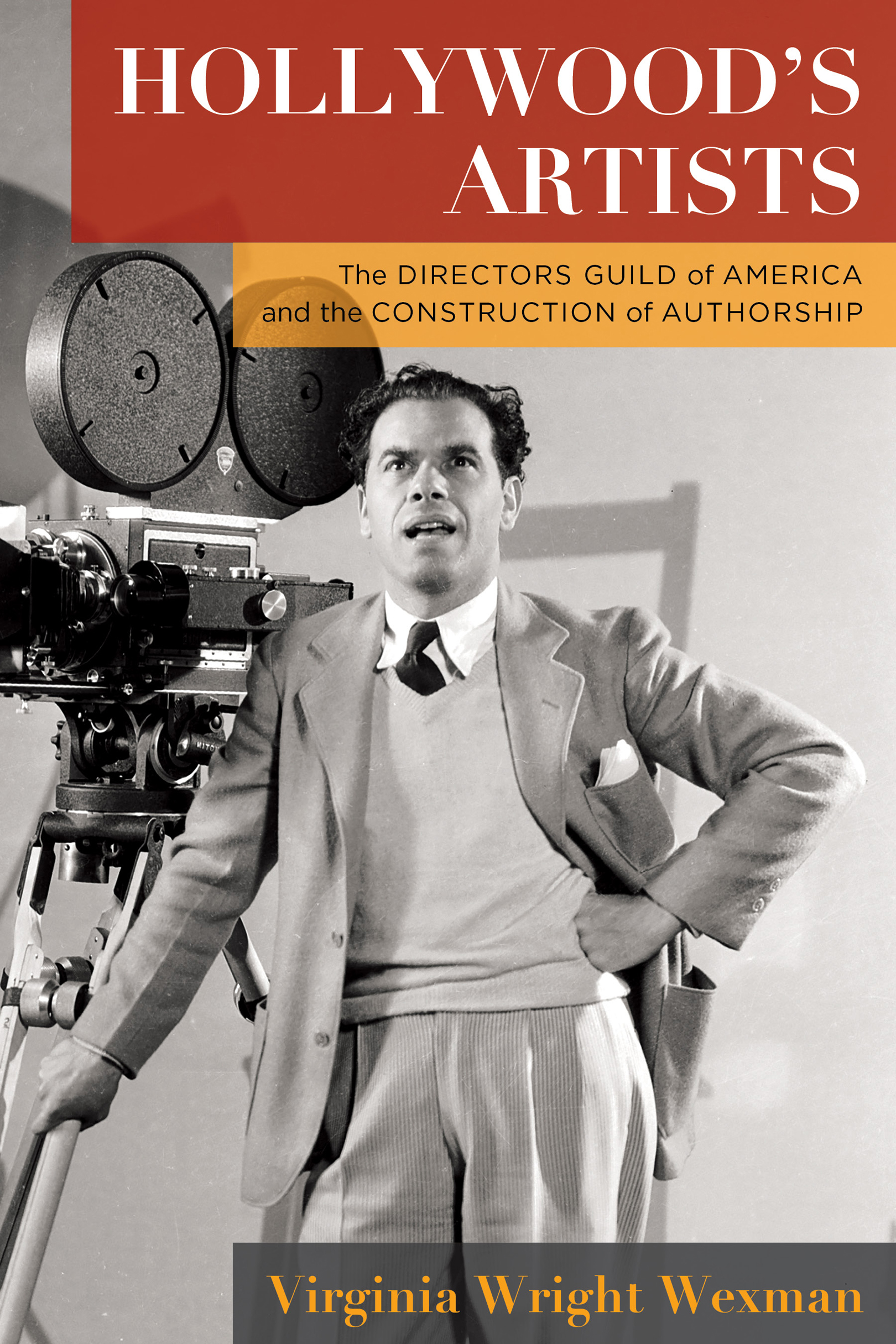

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover image: Moviepix Collection / John Kobal Foundation / Getty Images

Contents

My understanding of issues facing the Directors Guild of America has been aided by the opportunity to interview many people with significant roles in the organization. These interviews, all conducted in 2001, were arranged by Gina Blumenfeld, then the Guilds special projects executive, to whom I owe special thanks. Anthropologist Sherry Ortner has written about the difficulties inherent in gleaning information from members of an industry long famous for its predilection to control its image. I was fortunate in not encountering any of the difficulties Ortner enumerates, finding many people who gave generously of their time and helped me to appreciate the human element that grounds the work the DGA does. I had lengthy discussions with four of the Guilds former presidents: Gene Reynolds, Arthur Hiller, Gilbert Cates, and Martha Coolidge. DGA board member and future president Paris Barclay shared his thoughts on the organizations efforts to advance the careers of its minority members, and Elliot Silverstein, who then headed up the Artists Rights Foundation, patiently elucidated some of the legal intricacies his group was grappling with at the time. The DGAs executive director, Jay Roth, and associate executive director, Warren Adler, also talked with me at length. All of these native informants spoke eloquently and with great pride about the Guilds creative rights achievements.

During the long journey this project has taken on the road to publication, my efforts have also been aided by myriad colleagues, librarians, archivists, friends, and family memberstoo many to mention. However, I must offer special thanks to Jane Gaines, who read some early drafts of the manuscript and offered wise and encouraging critiques. Tony Gardner and Robert Marshall guided me through the Directors Guild files deposited in the Oviatt Library Special Collections department at California State University, Northridge. Ned Comstock at the University of Southern California Library and Jenny Romero at the Margaret Herrick Library both went above and beyond expectations to locate relevant materials for me. Colleagues at an array of events at which I read papers about the DGA, including the Columbia University Film Seminar, the Chicago Film Seminar, the University of Illinois English Department Symposium, and several Society for Cinema and Media Studies conferences, proffered useful suggestions.

After I submitted a draft of the manuscript to Columbia University Press, the editors worked with me creatively and carefully on the final refinements.

The contributions of my husband, John Huntington, could never be quantified; suffice it to say, this book would never have been possible without his continued support, input, and advice.

It is a question of describing the gradual emergence of the entire set of social conditions which make possible the character of the artist as a producer of the fetish which is the work of art.

Pierre Bourdieu

There can be no definitive critique of genius or talent that doesnt first take into consideration the social determinism, the historical combination of circumstances, and the technological background which to a large extent determine it.

Andr Bazin

I, for one, am sure that the super-author of pictures will in the not too distant future rise like a colossus in our midst.

Jesse L. Lasky

Today, the stock of Hollywood directors is high. Some observers see the trend as a long-overdue recognition of film artists whose shaping hand has, in the past, often been unjustly ignored by a philistine public and a mendacious corporate industry. A more economically oriented line of thought looks to the breakup of the old studio system and the rise of the independent film movement in the 1970s and 1980s as the key to unlocking the power of directorial talent. Other commentators see Hollywoods growing emphasis on marketing as a gift to directors, whose names are now routinely used to help sell the films they helm. The new knowledge that film critics and scholars have produced, most notably the focus on directors championed by auteurists, has played a role as well. In addition, directors have been given a boost by a growing film festival culture that promotes the names of favored cineastes. But another factor is rarely mentioned in discussions of the prominence of Hollywood directors in todays public realm: the active role played by their institutional base, the Directors Guild of America (DGA).

The preeminent place Hollywood directors occupy both in the film industry and in the public mind was not predetermined; it was enabled by trends within the culture at large and, as this book demonstrates, it was fought for by the DGA, through its creative rights program. From the moment of the Guilds foundingand even beforecreative rights have been a central preoccupation of Hollywood directors, driving an agenda that has enjoyed remarkable success over the years. Its goal is to make directors into artists.

From the time a dozen major directors founded it in 1935, the DGA has grown to become a many-faceted organization with more than 1,500 members, including assistant directors and unit managers as well as directors. It is the smallest of the three major talent groups in Hollywood (the actors and writers are the other two). Yet, by the turn of the millennium, references to the DGA in the Hollywood trade press routinely included the adjective powerful. The Guild draws its strength from several sources. Like the actors, the directors can force a work stoppage. Moreover, the managerial aspects of directors jobs on the set and their role as liaisons between the artisans who create movies and the business interests that finance them give DGA members a strategic advantage over the writers, actors, and below-the-line participants.