Joshua Prager - The Echoing Green

Here you can read online Joshua Prager - The Echoing Green full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

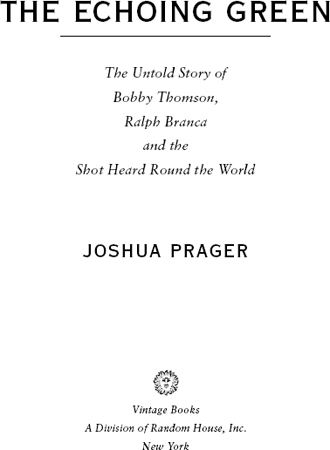

- Book:The Echoing Green

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Echoing Green: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Echoing Green" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Echoing Green — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Echoing Green" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

PART ONE

Our Sports Shall Be Seen

PART TWO

The Darkening Green

PART THREE

Such Were the Joys

October 3, 1951

To Bobby Thomson and Ralph Branca

And to Claire Gronich, my Bubster,

who always read aloud the name of the author

The Sun does arise,

And make happy the skies.

The merry bells ring

To welcome the Spring.

The sky-lark and thrush,

The birds of the bush,

Sing louder around,

To the bells chearful sound.

While our sports shall be seen

On the Ecchoing Green.

Old John with white hair

Does laugh away care,

Sitting under the oak,

Among the old folk,

They laugh at our play,

And soon they all say.

Such such were the joys.

When we all girls & boys,

In our youth-time were seen,

On the Ecchoing Green.

Till the little ones weary

No more can be merry

The sun does descend,

And our sports have an end:

Round the laps of their mothers,

Many sisters and brothers,

Like birds in their nest,

Are ready for rest;

And sport no more seen,

On the darkening Green.

The Ecchoing Green,

WILLIAM BLAKE, 1789

PROLOGUE

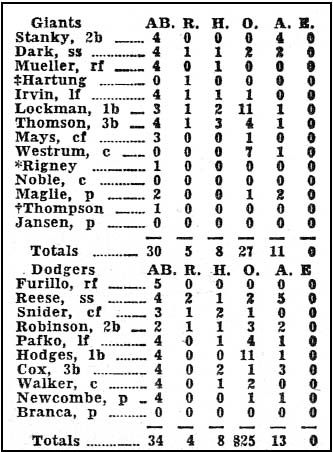

ON OCTOBER 3, 1951, Milton Glassman sat on a brick stoop in Forest Hills tuned to a baseball game. His Philco radio wore him thin, the cabdriver and Giant fan listening as New York and Brooklyndeadlocked after 156 games, seven innings and six monthsat last diverged, his team down 41 in the eighth. But single, single, foul-pop and double, dared hope in the bottom of the ninth, in the final half-inning of a season. And when at 3:58 p.m. Bobby Thomson lifted a Ralph Branca fastball over a green wall for a 54 win, Glassman thrust his only child overhead and let go. Four days shy of his third birthday, the boy flew high.

His flight above 99th Street remains today a very first memory for Marc Glassman. And for millions more, the blast that sent him heavenward remains after fifty-five years as indelibly marked.

Every American male over thirty can remember three things, wrote Wells Twombly in 1971. (1) Where he was the day he proposed to his wife, (2) where he was the day he heard the news that President Kennedy was shot and (3) where he was when he heard Russ Hodges describe the greatest home run of the century. Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins compiled a different list: Thomson home run, Kennedy assassination, Pearl Harbor, the death of Franklin Roosevelt. Author Ray Robinson added to those four 9/11. And poet Jonathan Williams recounted his own life by telling where he was during the Cuban missile crisis, when Roosevelt died and when Thomson hit the home run, Thomson the only constant in the gauge of American memory.

That a home run was more than the ethereal cap of a pennant race was clear. And so over the years, it was christened the Shot Heard Round the World and honored with a stamp and voted by the Sporting News the greatest moment in baseball history. John Steinbeck, Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth and Don DeLillo saluted it on paper. Francis Ford Coppola, M*A*S*H, Woody Allen and The Simpsons paid homage on screen. The home run was a life markerunfading whether miracle or trauma. Wrote Stephen Jay Gould: I have never known a greater moment of pure joy. Wrote Larry King: No day of my life since has brought me the pain of that day. Said Tallulah Bankhead: Today was the happiest day of my life. Said Dick Schaap: When Bobby Thomson hit the home run, my childhood ended.

Great as the wake of a home run was, it upended none more than Thomson and Branca. For one playoff pitch forever turned opponents to dyad, to hero and goat, each to hear tell of it a majority of their remaining days, each left to wonder for a lifetime why it meant so much to so many (and why, for example, the pennant-winning home run in the last inning of the 1950 season was quickly forgotten).

Of course, there were answersbooks and poems and sermons and essays to explain that a home run flew in New York, that a rivalry was rabid, a radio call sublime, a national television feed historic. But the full effect of a home run on its co-protagonists went unexamined. For in all the exegeses of a singular moment, one crucial element went missing, unknown that autumn afternoon even to the nine Dodgers afield, the 34,320 spectators at the Polo Grounds, the millions who followed the flight of a ball on radio and television. On October 3, 1951, a Giant peered through a Wollensak telescope at the Dodger signs, the finger signals transmitted from catcher to pitcher that determine the pitch to be thrown. The most famous of 240,000 home runs had a secret. And the effect on Thomsonand later Brancaof keeping that secret was, in time, every bit as profound as the effectiveness of a scheme hatched one rainy day in Harlem in July of 1951.

PART ONE

Our Sports Shall Be Seen

ONE

Now do you understand serendipity?

HORACE WALPOLE, letter to

Horace Mann, January 28, 1754

T HE SKY ABOVE BROOKLYN darkened in seconds, a borough plunged into dusk five minutes after noon. It was July 18, 1951, and in offices downtown, people turned on lights and peered out windows. A squall in Brooklyn Heights toppled a tree on Willow Place onto three parked cars. A bolt of electricity cracked, hailstones big as marbles pelting Borough Hall. Gusts of wind rocked Sheepshead Bay, small boats radioing distress. The temperature freefell from a balmy 80 to 69 degrees and it began to pour, sheets of rain flooding Prospect Park, empty garbage cans afloat in Flatbush, eighteen inches of water cascading onto the tracks of the Grand Army Plaza subway station. Service halted.

The blitzkrieg stopped abruptly at 12:40 p.m. And born of a cold front in Canada, it all but sidestepped Manhattan, the IRT leading to the Polo Grounds just fine. Still, it was the second-to-smallest crowd of the season that wended this Wednesday to the Harlem field, just 3,538 folks come to watch Giants versus Cubs.

Turnout would no doubt have been smaller still were it not for Willie Howard Mays Jr. Mays was a rookie. The child of an Alabaman railroad porter, he had joined the Giants just twenty years, eighteen days old, the youngest black ever called to the major leagues. And on that May day had all New York excited. For in thirty-five AAA games, the center fielder had hit a startling .477.

Harlem had pulsed with pride when Jackie Robinson turned Dodger, Larry Doby Indian, Monte Irvin Giant, Sam Jethroe Brave. But it was the great black ballplayers in Brooklyn to whom Harlem gave its 700,000 hearts. Wrote poet Langston Hughes in 1950.

On sunny summer Sunday afternoons in Harlem

when the air is one interminable ball game

and grandma cannot get her gospel hymns

from the Saints of God in Christ

on account of the Dodgers on the radio.

It was however a black Giant who now bunked at the corner of St. Nicholas and 155th Street, Mays renting the first floor of a boarding house owned by a woman named Ann Goosby. And quickly did Harlem take to Mays as it had to no Giant before. For the pheenom brought to the north end of Sugar Hill not only three 34-ounce bats but humanity. Willie, not William, was his given name. He weighed just 170 pounds, stood two inches shy of six feet. His black wool cap flew off mid-gallop. He scolded his Rawlings mitt when it dropped a ball. One hitless night in Philly, well along an anemic 1. for-26 start at bat, Mays sobbed. But oh that first hita home run off Warren Spahn that left its mark on both the left-field roof of the Polo Grounds and Leo Durocher. Cooed the Giant manager, I never saw a fucking ball get out of a fucking ball park so fucking fast in my fucking life. Harlem was in love.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Echoing Green»

Look at similar books to The Echoing Green. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Echoing Green and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Joshua Backfield [Joshua Backfield] - Becoming Functional](/uploads/posts/book/120483/thumbs/joshua-backfield-joshua-backfield-becoming.jpg)