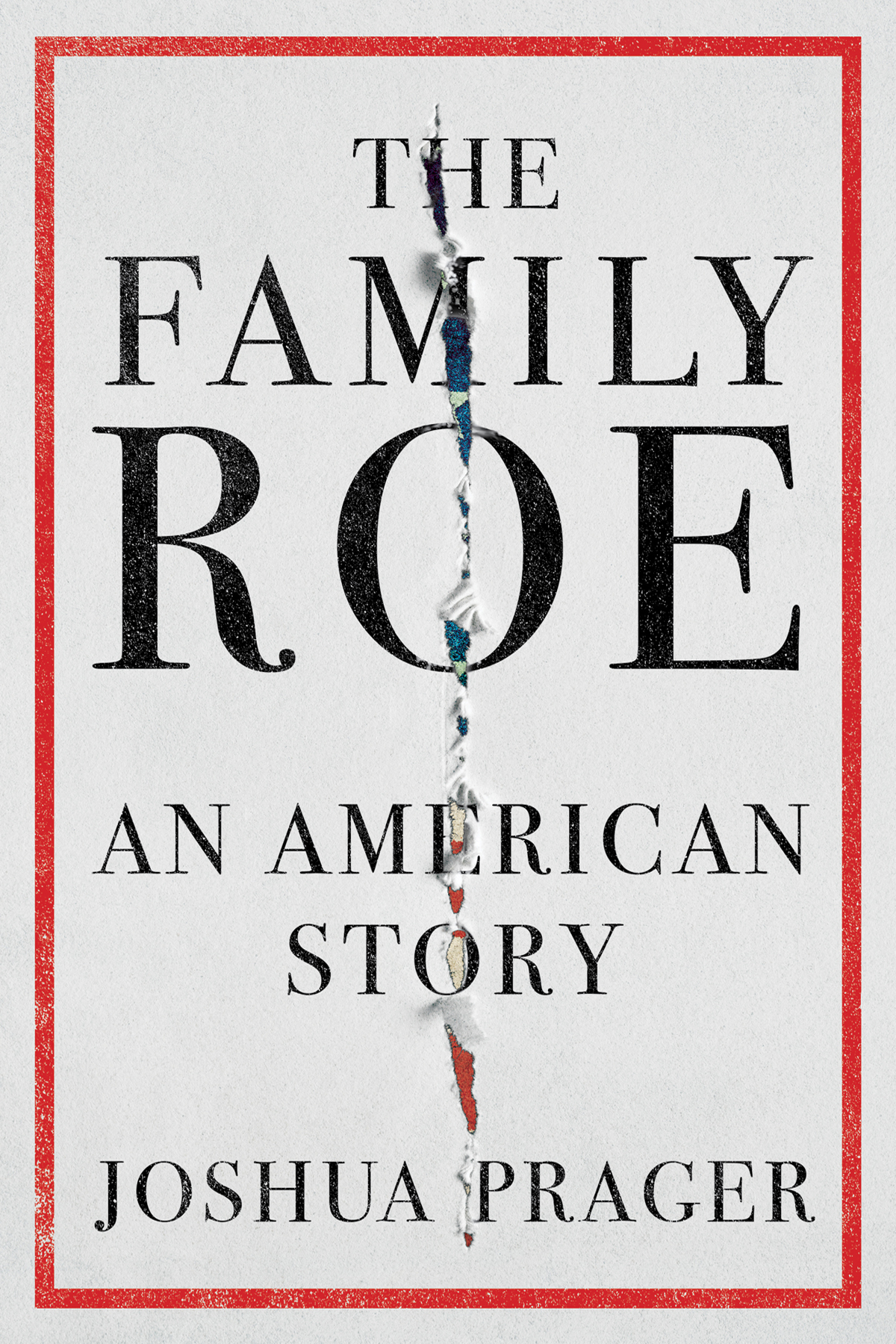

Joshua Prager - The Family Roe

Here you can read online Joshua Prager - The Family Roe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Family Roe

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Family Roe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Family Roe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Family Roe — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Family Roe" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE

FAMILY

ROE

An American Story

JOSHUA PRAGER

To my treasures,

Ella Vita and Eden Max

Be it said... see how elastic our stiff prejudices grow when love once comes to bend them.

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Contents

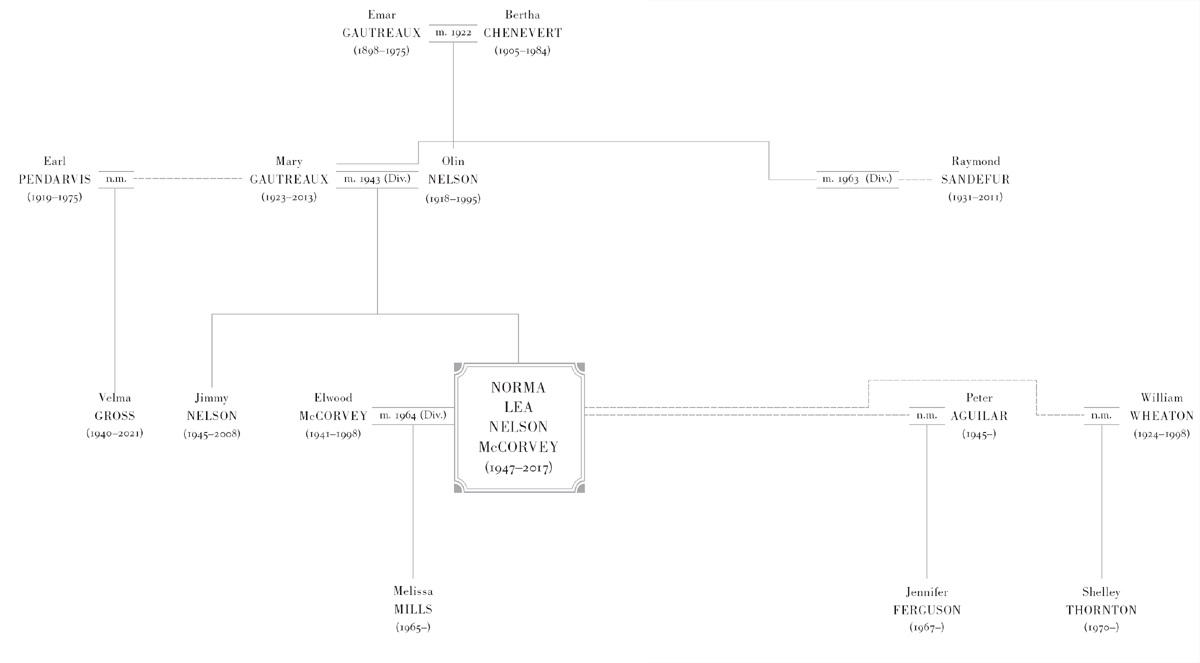

This tree only includes family members who feature prominently in the book.

O n January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, granting women the right to an abortion free of interference by the State.

The Court was undecided at first where in the Constitution to ground that right. It settled on the Fourteenth Amendment, ruling that it guaranteed Americans a right to privacy, and that a right to privacy secured a right to have an abortion.

There were some, even among the pro-choice, who assailed Roes reasoning. The feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg would later argue, in an article she wrote while a member of the DC Circuit appeals court, that the right to abortion ought to be grounded in equality, not privacy. But others applauded Roes logic and its author, too, the Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun. Six of his eight fellow justices joined his opinion, and its longevity was assumed; when nearly three years later Gerald Ford nominated John Paul Stevens to the Supreme Court, the Senate did not even ask the judge his opinion of it.

But the fault line that is abortion in America began then to slip and heave, to produce tremors not only of politics and law but of religion and sex, the stuff that quakes the puritanical foundations of this country like little else. And today, to hear both pro-life and pro-choice tell it, the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court nominees are above all referenda on Roe.

Roe has come to dictate far more than judicial appointments. It is, as the legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin wrote, undoubtedly the best-known case the United States Supreme Court has ever decided. More, it is the most enduringly divisive. There is no surer indicator of political affiliation in America than Roe, the ruling a Rorschach test and a rallying cry, a means not only to party consensus but donor dollarsmillions determined to uphold it, millions determined to overturn it.

Today, fifty years after the Court first heard arguments in Roe, the decision is hanging by a thread. Whether it falls or not, the American divide on abortion will remain. Any victory, no matter how sweeping, will simply trigger a new round of fighting, writes Mary Ziegler, a law professor expert on the American abortion debate. She adds: the abortion conflict is a tale of hopeless polarization, personal hatreds and political dysfunction.

Indeed, ours is a nation divisible by Roe. And as Blackmun noted in his preamble to the ruling, it is often personal experienceexposure to the raw edges of human existencethat determines which side of that divide one is on. The justice might have added that four years before he joined the Court, his daughter Sally had found herself unhappily pregnant in college.

ROE V. WADE WAS so named for its pseudonymous plaintiff, Jane Roe, and its defendant, Dallas district attorney Henry Wade. But at its heart, the case did not pit Roe against Wade; it pitted her against the fetus she was carrying. And the Courts ruling alluded, if only obliquely, to the existence of the child that fetus became. Wrote Blackmun: the normal 266-day human gestation period is so short that the pregnancy will come to term before the usual appellate process is complete.

Blackmun was making a simple legal point: it did not matter that the gestation of a lawsuit is longer than the gestation of a baby. The case had not been rendered moot because its plaintiff was no longer pregnant. But Blackmun did not write that Jane Roe had given birth. And the public was left to assume that Jane Roewhoever she washad gotten the abortion made legally available to her.

Normally, a plaintiff is required to use her real name. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure demand it. But, owing to the stigma of abortion, an exception was made in Roe, and Blackmun addressed it. Despite the use of the pseudonym, he wrote, no suggestion is made that Roe is a fictitious person.

Jane Roe was real. Her name was Norma McCorvey. And when, in 2010, I read an article that mentioned that Roe had been decided too late for Norma to have an abortion, I wondered about the baby shed placed for adoption forty years before. I decided to look for her.

Months after Norma gave birth to that child in 1970, she met her lifelong partner, Connie Gonzales. Norma had just left Gonzales when, in June 2010, I visited Gonzales at her Dallas home. She told me that the stories Norma had told about herself were not true.

Gonzaless home was due to be foreclosed on when I returned to see her the next year. She pointed me to a cache of papers that Norma had left behind in the garage and did not want. Looking through her speeches and letters, her holy cards and sheet music, I wondered not only about the Roe baby but about the other two daughters Norma had let go. I wondered also about Norma. Lifting a picture of Norma as a toddler atop a pony, I looked at the little house behind her up on piers and wondered, too, about her family rooted there on the banks of a Louisiana river.

Chapter 1

T he Atchafalaya River flows south from a small Louisiana town called Simmesport, where, in the fifteenth century, it branched off the Mississippi. The river runs to the Gulf of Mexico, traveling 137 miles through a triangle of Louisiana locals call Acadiana. The name recalls Acadia, the bygone French colony in northeastern North America. There, starting in 1755, thousands of French exiles were driven from their homes. They began, nine years later, to settle along a Louisiana river two thousand miles to the southwest.

No locks or levees or dams yet harnessed the young river. And the Acadiansas those early Americans would be calledthough they dug furrows and ditches beside the river and set their huts atop blocks of cypress, often found themselves in water. If the river flooded, it also bore crawfish and silt, the sediment feeding crops of soybean and indigo. More crops followed: tobacco, cotton, maize, molasses, sugar. The Acadians soon owned plantations and people, tooAfricans working their fields, breastfeeding their young. Their community grew; by the early nineteenth century, there were roughly five thousand Acadians in Louisiana. They gave its marshes and bayous and prairies French names: Prairie Basse, Prairie des Femmes, Prairie des Coteaux.

Francophone and Catholic, the Acadians took to the Southto its fiddles and faith healers, its Spanish moss and slavery. By 1860, forty-nine Acadians owned more than fifty slaves each. But they were no patriots. Flags changed; the Acadians had already seen the French, Spanish and Americans govern this land. When the Confederate Army conscripted their men, the Acadian soldier was all but indifferent to the cause. Some surrendered. Some deserted.

When the war ended, the Acadians had lost their slaves and infrastructure, and many became fishermen or trappers or lumberjacks. But having previously filled steamboats and trains with produce for export, they now struggled to feed their own. Poverty took hold. Starvation was endemic. Alcoholism, too. More and more, as historian Carl Brasseaux noted, Acadians came to be thought of as primitive, as ignorant, as Cajunthe word a derisive variant of Acadian.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Family Roe»

Look at similar books to The Family Roe. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Family Roe and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Joshua Backfield [Joshua Backfield] - Becoming Functional](/uploads/posts/book/120483/thumbs/joshua-backfield-joshua-backfield-becoming.jpg)